Defining regenerative agriculture

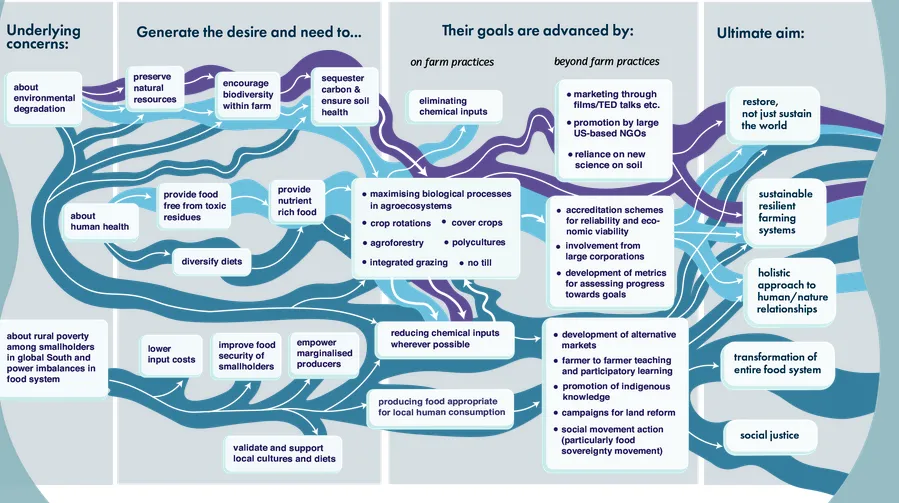

Definitions of regenerative agriculture cluster into three (overlapping) kinds. There are those that emphasise specific practices; those that focus on desired outcomes; and those that envision a new way of relating to one another and the natural world – a regenerative mindset.

Regenerative agriculture as a set of practices

A key practice within regenerative agriculture is the maintenance of soil fertility and its wider ‘health’. Soil fertility refers to the capacity of soil to support crop growth and is primarily described in terms of levels of specific nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, etc). Meanwhile, soil health relates to more diffuse ideas like the importance of natural cycles, high levels of biodiversity, and its ability to deliver ecosystem services. Soil health is maintained in several ways.

| Objective | Associated methods | Proposed benefits |

| Maintain soil cover. |

|

|

| Limit mechanical disturbance of the soil. |

|

|

| Limit chemical disturbance of the soil. |

|

|

| Keep living roots in the soil. |

|

|

Another aim of regenerative agriculture is to promote biodiversity and shift away from highly simplified monocultural systems. This can lead to pest suppression, soil fertility, and soil health becoming emergent features of the system, reducing reliance on chemical inputs. This can be achieved in various ways:

- Diversification of crops grown in an arable rotation, particularly including legumes.

- Diversification of cover crop or pasture seed mixes.

- Promotion of biodiversity on land spared for non-agricultural purposes by planting hedgerows, sowing wildflowers, etc.

- Shifting to polyculture systems such as agroecology.

Regenerative agriculture also looks to crop-livestock integration to promote environmental benefits compared to current conventional systems. This can be done in a variety of ways, such as including forage crops in an arable rotation, or grazing livestock on temporary grass-based leys to increase soil carbon stocks in an otherwise arable system. However, it is notable that these measures may reduce crop yields so the environmental risks of compensatory cultivation or stocking with ‘additional’ livestock (and associated emissions from ruminant enteric fermentation) must be mitigated. See “What is feed-food competition?” for more detail.

Regenerative agriculture as a set of outcomes

Rather than focusing on practices, some define regenerative agriculture based on its intended outcomes. Specifically, they emphasise aiming for agroecosystem (particularly soil) restoration and empowering farmers to achieve this goal using context-specific approaches. For example, farmers may employ practices (e.g., soil tillage) usually discouraged in the regenerative model if they achieve regenerative outcomes (it’s not the plough, it’s the how).

To achieve these goals environmental metrics would be required as a proxy for ecosystem and soil health to give farmers, commercial and political actors a robust and legally-defensible evidence-base for regenerative outcomes. Debate remains over which metrics provide the required information cost- and time-effectively but empirical tools (like the Global Farm Metric and Soilmentor) are emerging to fulfil this need. Metrics may also include social outcomes like better mental health and profitability for farmers.

Regenerative agriculture as a mindset

Viewed as a mindset, regenerative agriculture focuses more on attitudes towards the co-vitality of humans and nature than specific farming practices. Here, regeneration is an ongoing journey – a continuously evolving process of experimentation taking place within interconnected ecological systems. This mindset also stresses complementing scientific knowledge with spiritual and emotional engagement with a farmed landscape. This creates an adaptive, generative, and open-ended sense of regeneration. Whilst this lacks the robust definitions needed by purely commercial and political actors, many consider a mindset approach essential for achieving more expansive social objectives. These include promoting farmer-consumer interaction, farmer mental health, rural economy resilience, and redistribution of power in the food system.

Is a consensus definition needed?

The lack of clear definition may be the very reason regenerative agriculture has catalysed such diverse ideas for food system transformation from such a wide variety of actors. Rather than competing, the differing articulations could constitute different tiers on the same regenerative framework. A tiered framework may encourage actors starting on the regenerative journey (with practices) to go on to engage more with wider psychological, ecological, and political ambitions.

A ‘broad church’ approach that welcomes various actors (from radical elements to corporate actors) and accepts overlap with other approaches (permaculture, organics, agroecology) would allow a highly adaptive form of regenerative agriculture. For example, in the right context, farmers could remove central planks of the movement (like no-till management), and their farms would remain ‘regenerative’. Here, a family resemblance definition may be required: a cluster of practices and principles can be considered integral to regenerative agriculture, but none of which is, unto itself, a necessary condition.

Comments (0)