Footnotes

168 Cicely D. Williams, ‘A NUTRITIONAL DISEASE OF CHILDHOOD ASSOCIATED WITH A MAIZE DIET’, Archives of Disease in Childhood 58 (1933): 559.

169 Williams, 559.

170 H. S. Stannus, ‘A Nutritional Disease of Childhood Associated with a Maize Diet--and Pellagra’, Archives of Disease in Childhood 9, no. 50 (1 April 1934): 115–18, https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.9.50.115.

171 Cicely D. Williams, ‘KWASHIORKOR’, The Lancet 226, no. 5855 (November 1935): 1151–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)94666-X.

172 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 142–45; Joshua Nabilow Ruxin, ‘Hunger, Science, and Politics: FAO, WHO, and Unicef Nutrition Policies, 1945-1978’ (Ph.D., London, University College London, 1996), 37; Kimura, Hidden Hunger, 23.

173 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 145–49; Nott, ‘“No One May Starve in the British Empire”’, 566.

174 Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Nutrition, Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Nutrition: Report on the First Session, Geneva, 24-28 October 1949. (Geneva: World Health Organization, 1950), 15.

175 Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Nutrition, 16.

176 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 149; Richard D. Semba, ‘The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health’, Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 69, no. 2 (2016): 80, https://doi.org/10.1159/000449175.

177 J. F. Brock and M. Autret, ‘KWASHIORKOR IN AFRICA’, Bulletin of the World Health Organization 5 (1952): 1–71 particularly cf. 49.

178 Indeed, even human breastmilk was judged too low in protein for infants—which in retrospect should perhaps have rendered the results suspect. Apparently the idea that it was normal good practice to supplement infant feeding with (higher protein) cow’s milk was so deeply accepted that this passed without comment.

179 Semba, ‘The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health’, 80.

180 Ruxin, ‘Hunger, Science, and Politics: FAO, WHO, and Unicef Nutrition Policies, 1945-1978’, 72.

181 Semba, ‘The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health’, 81.

182 Brock and Autret, ‘KWASHIORKOR IN AFRICA’, 29.

183 Semba, ‘The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health’, 80.

184 Kimura, Hidden Hunger, 24; Richard D. Semba, ‘The Historical Evolution of Thought Regarding Multiple Micronutrient Nutrition’, The Journal of Nutrition 142, no. 1 (1 January 2012): 148S, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.137745.

185 Lindsay Hamilton, Marylyn Carrigan, and Camille Bellet, ‘(Re)Connecting the Food Chain: Entangling Cattle, Farmers and Consumers in the Sale of Raw Milk’, The Sociological Review 69, no. 5 (September 2021): 1107–23, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026121990975; it is also interesting to note that the ‘Special Milk Program’ began distributing milk to school children in the US in 1954 - Susan Levine, School Lunch Politics: The Surprising History of America’s Favorite Welfare Program, Course Book (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 93.

186 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 152–53.

187 Protein Advisory Group, ‘Lives in Peril: Protein and the Child’, World Food Problems (FAO/WHO/UNICEF, 1970).

188 Semba, ‘The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health’, 81.

189 Pauline K. Marstrand, ‘Production of Microbial Protein: A Study of the Development and Introduction of a New Technology’, Research Policy 10, no. 2 (July 1981): 168, https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(81)90003-2.

190 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 163–64.

191 Carpenter, 165–68; Ernst R. Pariser et al., Fish Protein Concentrate: Panacea for Protein Malnutrition?, International Nutrition Policy Series 3 (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1978).

192 Richard Westlake, ‘Large-scale Continuous Production of Single Cell Protein’, Chemie Ingenieur Technik 58, no. 12 (1986): 934–37, https://doi.org/10.1002/cite.330581203; I. Y. Hamdan and J. C. Senez, ‘The Economic Viability of Single Cell Protein (SCP) Production in the Twenty-First Century’, in Biotechnology: Economic and Social Aspects, ed. E. J. DaSilva, C. Ratledge, and A. Sasson, 1st ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1992), 142–64, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511760075.008.

193 Marstrand, ‘Production of Microbial Protein’.

194 Juha Koivurinta, Rakel Kurkela, and Pekka Koivistoinen, ‘Uses of Pekilo, a Microfungus Biomass from Paecilomyces Varioti in Sausage and Meat Balls’, International Journal of Food Science & Technology 14, no. 6 (December 1979): 561–70, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1979.tb00902.x.

195 A. J. Forage, ‘III Utilization of Agricultural and Food Processing Wastes Containing Carbohydrates’, Chemical Society Reviews 8, no. 2 (1979): 309, https://doi.org/10.1039/cs9790800309.

196 Hamdan and Senez, ‘The Economic Viability of Single Cell Protein (SCP) Production in the Twenty-First Century’; M. García-Garibay et al., ‘SINGLE CELL PROTEIN | Yeasts and Bacteria’, in Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Elsevier, 2014), 431–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384730-0.00310-4.

197 Hamdan and Senez, ‘The Economic Viability of Single Cell Protein (SCP) Production in the Twenty-First Century’, 146; García-Garibay et al., ‘SINGLE CELL PROTEIN | Yeasts and Bacteria’, 431.

198 Specifically, humans and some related primates have lost the ability to produce urate oxidase. As a result, purines, including adenine and guanine which are components of DNA, are only metabolised into uric acid in humans instead being further oxidised. High blood levels of urates are then associated with gout and kidney stones. X W Wu et al., ‘Urate Oxidase: Primary Structure and Evolutionary Implications.’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 86, no. 23 (December 1989): 9412–16, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.86.23.9412; Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 176.

199 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 175–77.

200 Mycoprotein derived from Fusarium venenatum has now even been suggested as the new standard for high quality dietary protein against which other sources should be judged. The species name—Fusarium venenatum is Latin for ‘venomous spindle’—seems a little ironic in retrospect. D Joe Millward, ‘Milk Protein Loses Its Crown?’, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 112, no. 2 (1 August 2020): 245–46, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa112.

201 Jack A. Whittaker et al., ‘The Biotechnology of Quorn Mycoprotein: Past, Present and Future Challenges’, in Grand Challenges in Fungal Biotechnology, ed. Helena Nevalainen, Grand Challenges in Biology and Biotechnology (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020), 59–79, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29541-7_3.

202 Note that Quorn Foods Ltd. claims that their process creates more protein per tonne of wheat than was contained in the wheat: thus quorn as a technology could theoretically still increase the availability of protein, even though it is grown on feedstock that humans could eat. I have not been able to precisely reproduce these calculations, however. Quorn Foods Ltd., ‘Quorn Sustainable Development Report 2017’ (Stokesley, North Yorkshire, 2017), 14–15, https://www.quorn.co.uk/files/content/Sustainable-Development-Report-2017.pdf.

203 Anthony P.J. Trinci, ‘Myco-Protein: A Twenty-Year Overnight Success Story’, Mycological Research 96, no. 1 (January 1992): 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80989-1; T. Sharp, ‘Quorn Myco-Protein: The Development of a New Food and Its Contribution to the Diet’, in Food and Nutrition Policy in Europe (The Second European Conference on Food and Nutrition Policy, The Hague 21 - 24 April 1992, Wageningen: Pudoc Scientific Publishers, 1993), 149–54.

204 Aaron M. Altschul, Combating Malnutrition: New Strategies through Food Science, Remarks of Aaron M. Altschul, Special Assistant for International Nutrition Improvement to Secretary of Agriculture, to 2nd Joint Meeting of American Institute of Chemical Engineers and Institute de Ingenieros Quimicos de Puerto Rico, Tampa, Fla., May 21, 1968 (Washington, D.C: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1968); Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 161–78; Semba, ‘The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health’, 82–84.

205 Pariser et al., Fish Protein Concentrate.

206 Pariser et al., 52, 225–29; Edward Clay, ‘Book Review Article: Forty Years of Multilateral Food Aid: Responding to Changing Realities’, Development Policy Review 20, no. 2 (2002): 203–7; Kimura, Hidden Hunger, 24.

207 Francis E Calvert and William T Atkinson, PROCESS FOR THE PREPARATION OF HYDRATABLE PROTEIN FOOD PRODUCTS, United States Patent and Trademark Office US 3498794 A, filed 25 January 1965, and issued 3 March 1970.

208 Archer Daniels Midland Company, TVP, United States Patent and Trademark Office 81014793 (Decatur, Illinois, filed 19 October 1973, and issued 1 July 1975), https://tsdr.uspto.gov/#caseNumber=81014793&caseType=SERIAL_NO&searchType=statusSearch.

209 Ross Irwin, ‘Dwayne Andreas’s Bean Has a Heart of Gold’, Fortune, October 1973, 138.

210 USDA ARS, ‘Textured Vegetable Protein Products (B-1), FNS Notice 219’, 1971, https://www.kn-eat.org/insite/Insite_Doc/IntheKnow/USDAMemos/FNSInstructions/FNS%20219.pdf.

211 General Mills Inc., Bontrae, 72459090 (MINNEAPOLIS MINNESOTA, filed 1 June 1973, and issued 26 March 1974).

212 Duane C. Wosje, ‘TEXTURED VEGETABLE PROTEINS TO ALLEVIATE WORLD FOOD PROBLEMS’, Journal of Milk and Food Technology 33, no. 9 (1 September 1970): 405, 407, https://doi.org/10.4315/0022-2747-33.12.405; cf. also Kenneth M. Wolford, ‘Beef/Soy: Consumer Acceptance’, Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 51, no. 1Part2 (January 1974): 131A-133A, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02542111.

213 A cynic might note that the poor populations at risk of protein malnutrition were generally already accustomed to eating pulses, so new ways of making soybeans more palatable were most relevant for markets in the global north.

214 Aaron Altschul, Special Assistant for International Nutrition Improvement to the Secretary of Agriculture, stated in 1968 that “[m]ost of these new foods will be available first to people who probably do not need them [...] but [...] the first thing to do with a new food is to establish it in the marketplace”. Altschul, Combating Malnutrition: New Strategies through Food Science, Remarks of Aaron M. Altschul, Special Assistant for International Nutrition Improvement to Secretary of Agriculture, to 2nd Joint Meeting of American Institute of Chemical Engineers and Institute de Ingenieros Quimicos de Puerto Rico, Tampa, Fla., May 21, 1968, 13.

215 Frances Moore Lappé, Diet for a Small Planet (New York: Friends of the Earth / Ballantine Books, Inc., 1971).

216 Frances Moore Lappé, Anna Lappé, and Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute, Hope’s Edge: The next Diet for a Small Planet (New Delhi: Viveka Foundation, 2005), 56.

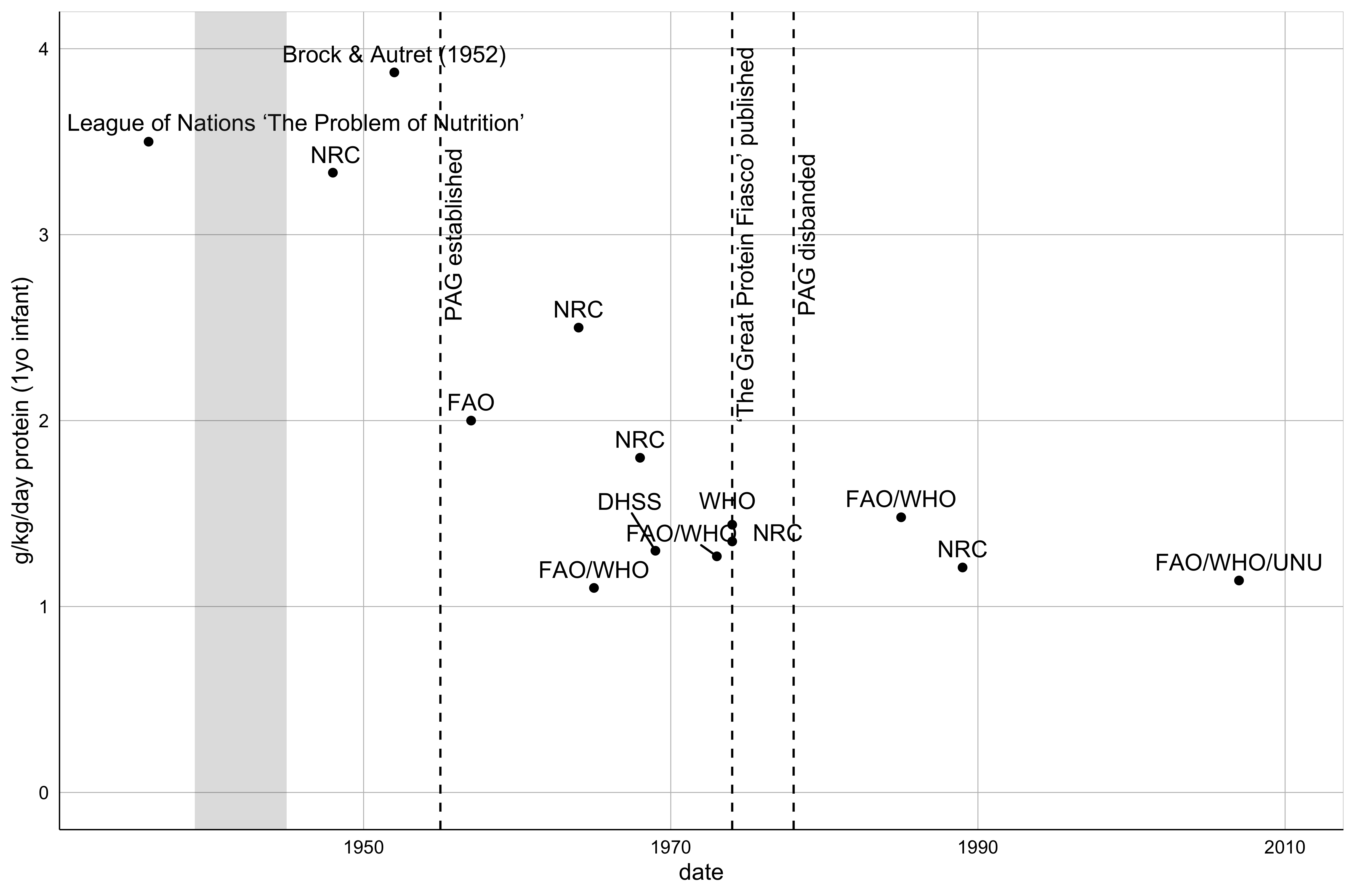

217 For context, Millward & Jackson (2007) estimated that a one-year-infant required only 0.875g protein per kg of body weight per day.

218 J. C. Waterlow and P. R. Payne, ‘The Protein Gap’, Nature 258, no. 5531 (November 1975): 113, https://doi.org/10.1038/258113a0. This is not the place to go into the unsolved debate around the aetiology of kwashiorkor in detail. Protein deficiency remains a major possibility, with suggestive evidence from recent work on blood albumin levels, but the epidemiological evidence speaks against an association between dietary protein intake and developing kwashiorkor. A non-exhaustive list of other explanations put forward includes deficiency of the sulphur amino acids (perhaps in combination with high intake of cyanogens from cassava), exposure to aflatoxins (produced by the fungus Aspergillus flavus), changes in gut microbiota, and oxidative stress resulting from sequential infections in combination with low micronutrient intake. In contrast to the great attention kwashiorkor received during the 1960s and 70s, researchers now describe it as an ‘orphan disease’, subject to little medical or epidemiological research in spite of the fact that it still affects hundreds of thousands of people per year. André Briend, ‘Kwashiorkor: Still an Enigma – the Search Must Go On’, CMAM Forum Technical Brief (CMAM Forum, December 2014), 25 and passim, https://www.ennonline.net/attachments/2314/Kwashiorkor-still-an-enigma-CMAM-Forum-Dec-2014.pdf; Edem M. A. Tette and Juliana Yartey Enos, ‘Letter to the Editor Aetiology of Kwashiorkor Then and Now–Still the Deposed Child?’, Asian Journal of Dietetics 2, no. 1 (2020): 41–42; Malcolm G. Coulthard, ‘Oedema in Kwashiorkor Is Caused by Hypoalbuminaemia’, Paediatrics and International Child Health 35, no. 2 (13 May 2015): 83–89, https://doi.org/10.1179/2046905514Y.0000000154; Thi-Phuong-Thao Pham et al., ‘Difference between Kwashiorkor and Marasmus: Comparative Meta-Analysis of Pathogenic Characteristics and Implications for Treatment’, Microbial Pathogenesis 150 (January 2021): 104702, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104702.

219 Cannon, ‘Nutrition’, S485.

220 UN General Assembly, ‘Protein Resources [A/RES/2848]’, in Resolutions Adopted by the General Assembly during Its 26th Session, 21 September-22 December 1971, 1972, 68–70.

221 Donald S. McLaren, ‘To the Editor’, Food and Nutrition Bulletin 20, no. 3 (January 1999): 369–70, https://doi.org/10.1177/156482659902000318.

222 Donald S. Mclaren, ‘THE GREAT PROTEIN FIASCO’, The Lancet 304, no. 7872 (July 1974): 93–96, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91649-3.

223 From 1974 on, attention began to be paid to notions of ‘food security’ (and later ’food sovereignty’) that moved beyond a simplistic understanding of malnutrition as the individual consequence of societal under-production of food. These newer frameworks engaged with questions of food distribution, access, affordability, reliability and safety, cultural preferences, dietary balance, and the loci of political and economic control over the food system. In this more complex picture, it might not make any sense to try to ‘diagnose’ a problem with the food system by looking for an imbalance between the dietary needs of the world population and global food production: more than enough food can be produced, yet people can still go hungry. For more discussion of food security and food sovereignty, see Walter Fraanje, Samuel Lee-Gammage, and Tara Garnett, ‘What Is Food Security?’ (Food Climate Research Network, 12 March 2018), https://doi.org/10.56661/e49a6c96; Rachel Carlile, Matthew Kessler, and Tara Garnett, ‘What Is Food Sovereignty?’ (TABLE, 25 May 2021), https://doi.org/10.56661/f07b52cc.

224 Semba, ‘The Rise and Fall of Protein Malnutrition in Global Health’, 84.

225 Donald S. Mclaren, ‘THE GREAT PROTEIN FIASCO’, The Lancet 304, no. 7888 (November 1974): 1079, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(74)92175-8.

226 Waterlow and Payne, ‘The Protein Gap’.

227 Mclaren, ‘THE GREAT PROTEIN FIASCO’, July 1974, 93.

228 P. V. Sukhatme, ‘Incidence of Protein Deficiency in Relation to Different Diets in India’, British Journal of Nutrition 24, no. 2 (June 1970): 477–87, https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN19700047; Donald S McLaren, ‘The Great Protein Fiasco Revisited’, Nutrition 16, no. 6 (June 2000): 464–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00234-3.

229 Willem Halffman, ‘Frames: Beyond Facts versus Values’, in Environmental Expertise: Connecting Science, Policy and Society, ed. Esther Turnhout, Willemijn Tuinstra, and Willem Halffman, 1st ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 36–67, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316162514.

230 Cannon, ‘Nutrition’; Kimura, Hidden Hunger; Nelson, Nisbett, and Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition’.

231 Rivers, ‘The Profession of Nutrition—an Historical Perspective’; Carpenter, ‘The History of Enthusiasm for Protein’.

232 Technical Commission of the Health Committee, The Problem of Nutrition, II: Report on the Physiological Bases of Nutrition:15; Cannon, ‘Nutrition’, S485; Waterlow and Payne, ‘The Protein Gap’, 114; Passmore et al., Handbook on Human Nutritional Requirements, 20; Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation, ‘Energy and Protein Requirements’, 104–5; D Joe Millward and Alan A Jackson, ‘Protein/Energy Ratios of Current Diets in Developed and Developing Countries Compared with a Safe Protein/Energy Ratio: Implications for Recommended Protein and Amino Acid Intakes’, Public Health Nutrition 7, no. 3 (May 2004): 387–405, https://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2003545.

Comments (0)