Footnotes

99 Treitel, ‘Max Rubner and the Biopolitics of Rational Nutrition’, 6.

100 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 79–88. J. H. Kellogg was actually the inventor of corn flakes, which he served at the sanatorium of which he was chief medical officer, but after a feud was forced to give up his rights to the invention to his brother. Kellogg is also credited with inventing peanut butter, and marketing an early meat substitute. Like Liebig and others, his beliefs about nutrition overlapped substantially with his entrepreneurial endeavours.

101 Dan Priel, ‘Law Is What the Judge Had for Breakfast: A Brief History of an Unpalatable Idea’, Buffalo Law Review 68, no. 3 (2020): 928–30.

102 Not all vegetarianism was religiously motivated by any means; for humanist vegetarians, however, the arguments were more about demonstrating the non-necessity of dietary animal protein than its actual harmfulness. Cf. Liam Young, ‘Eating Serial: Beatrice Lindsay, Vegetarianism, and the Tactics of Everyday Life in the Late Nineteenth Century’, Societies 5, no. 1 (22 January 2015): 65–88, https://doi.org/10.3390/soc5010065.

103 John M. Swan, ‘A Study of the Metabolism of a Vegetarian’, The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 129, no. 6 (June 1905): 1059; Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 88–99.

104 Mikkel Hindhede, Protein and Nutrition: An Investigation (London: Ewart, Seymour & Co., Ltd., 1913), 4–5.

105 For earlier researchers, the difficulty of finding test subjects willing to eat such restricted diets for a long period presented a significant barrier to this work—but, experimenting on his lab assistant and himself, Hindhede commented: “I have not encountered these difficulties.” [Diesen Schwierigkeiten bin ich nicht begegnet.]

106 Mikkel Hindhede, ‘Untersuchungen Über Die Verdaulichkeit Der Kartoffeln’, Skandinavisches Archiv Für Physiologie 27, no. 2 (26 April 1912): 277–94; M. Hindhede, ‘THE EFFECT OF FOOD RESTRICTION DURING WAR ON MORTALITY IN COPENHAGEN’, Journal of the American Medical Association 74, no. 6 (7 February 1920): 381, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1920.02620060015005. Note that the experiment was not entirely continuous: there were periods in the summer where they could not get potatoes, and Hindhede wrote the work up as a series of slightly different experiments whose total period was over a year. However, in the 1920 paper he summarised it as having shown that ‘man can retain full vigor for a year or longer on a diet of potatoes and fat’, and this rather simplified image of the work has had a long afterlife in popular culture.

107 Hindhede, Protein and Nutrition: An Investigation, 4.

108 Hindhede, 156.

109 cf. M. Hindhede, ‘Ueber den Einfluß der Nahrungsrationierung auf den Gesundheitszustand’, DMW - Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 46, no. 12 (March 1920): 318–20, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1192532.

110 cf. Simmons, Vital Minimum, 110.

111 Mikuláš Teich, ‘Science and Food during the Great War: Britain and Germany’, in The Science and Culture of Nutrition, 1840-1940, ed. Harmke Kamminga and Andrew Cunningham (BRILL, 1995), 213–34, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004418417; Corinna Treitel, ‘Food Science/Food Politics: Max Rubner and “Rational Nutrition” in Fin-de-Siècle Berlin’, in Food and the City in Europe since 1800, ed. P. J. Atkins, Peter Lummel, and Derek J. Oddy (Aldershot, England ; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007), 59; Kristen Ehrenberger, ‘The Politics of the Table: Nutrition and the Telescopic Body in Saxon Germany, 1890-1935’ (Ph.D., Urbana, Illinois, University of Illinois, 2014), 61, https://www.proquest.com/docview/1624890978.

112 Helen Breewood and Tara Garnett, ‘What Is Feed-Food Competition?’, Foodsource: Building Blocks (University of Oxford: Food Climate Research Network, 2020), https://www.tabledebates.org/building-blocks/what-feed-food-competition.

113 Hindhede, ‘THE EFFECT OF FOOD RESTRICTION DURING WAR ON MORTALITY IN COPENHAGEN’; Rabinbach, The Human Motor, 262–64; U Heyll, ‘Der „Kampf ums Eiweißminimum”’, DMW - Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 132, no. 51/52 (12 December 2007): 2768–73, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1012767; Stephan Rössner, ‘Mikkel Hindhede (1862-1945)’, Obesity Reviews 11, no. 3 (March 2010): 231–32, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00636.x.

114 With the fuller view of hindsight, it is worth noting that historians now agree that Germany’s disastrous experience of starvation in the War was more due to a lack of centralised planning of food and agriculture at all than to policies which privileged meat and protein. Rubner actually advocated similar policies to Hindhede: before the War he had argued that the poor should swap their meat for plant protein sources, and during the War he put a lot of focus on feed-food competition, writing ‘If we had no pigs, we’d have no food worries. Perhaps we’ll learn at least from the war, that swine husbandry is for the politics of food an example of insanity.’ That German nutritional policies were so unsuccessful had much to do with problems of implementation. Nevertheless, the consensus interpretation in the following decades blamed Rubner, “rational nutrition”, and proteincentricity. Heyll, ‘Der „Kampf ums Eiweißminimum”’, 2772; Treitel, ‘Max Rubner and the Biopolitics of Rational Nutrition’, 21–25; Ehrenberger, ‘The Politics of the Table: Nutrition and the Telescopic Body in Saxon Germany, 1890-1935’, 45.

115 Graham Lusk, Food in War Time (Philadelphia and London: W. B. Saunders Company, 1918); Henry C. Sherman, L. H. Gillett, and Emil Osterberg, ‘Protein Requirement of Maintenance in Man and the Nutritive Efficiency of Bread Protein’, Journal of Biological Chemistry 41, no. 1 (1920): 97–109.

116 Lafayette B. Mendel, Nutrition: The Chemistry of Life (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1923), 14–26.

117 Mendel, 24.

118 Hindhede, Die Neue Ernährungslehre, 5, cited in Mendel, 113.

119 although these had equally been associated with excess intake of carbohydrate; cf. John Nott, ‘“No One May Starve in the British Empire”: Kwashiorkor, Protein and the Politics of Nutrition Between Britain and Africa’, Social History of Medicine 34, no. 2 (28 May 2021): 553–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hkz107.

120 F.A. Dentz, ‘Hunger Oedema’, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 28 (June 1953): 93–112, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1952.tb10987.x.

121 Food (War) Committee, Report of the Food (War) Committee of the Royal Society on the Food Requirements of Man and Their Variations According to Age, Sex, Size, and Occupation (London: Harrison and Sons, 1919), 18, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/w45wte5r; Mendel, Nutrition: The Chemistry of Life, 120–24.

122 James S. McLester, Nutrition and Diet in Health and Disease (Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1939), 77.

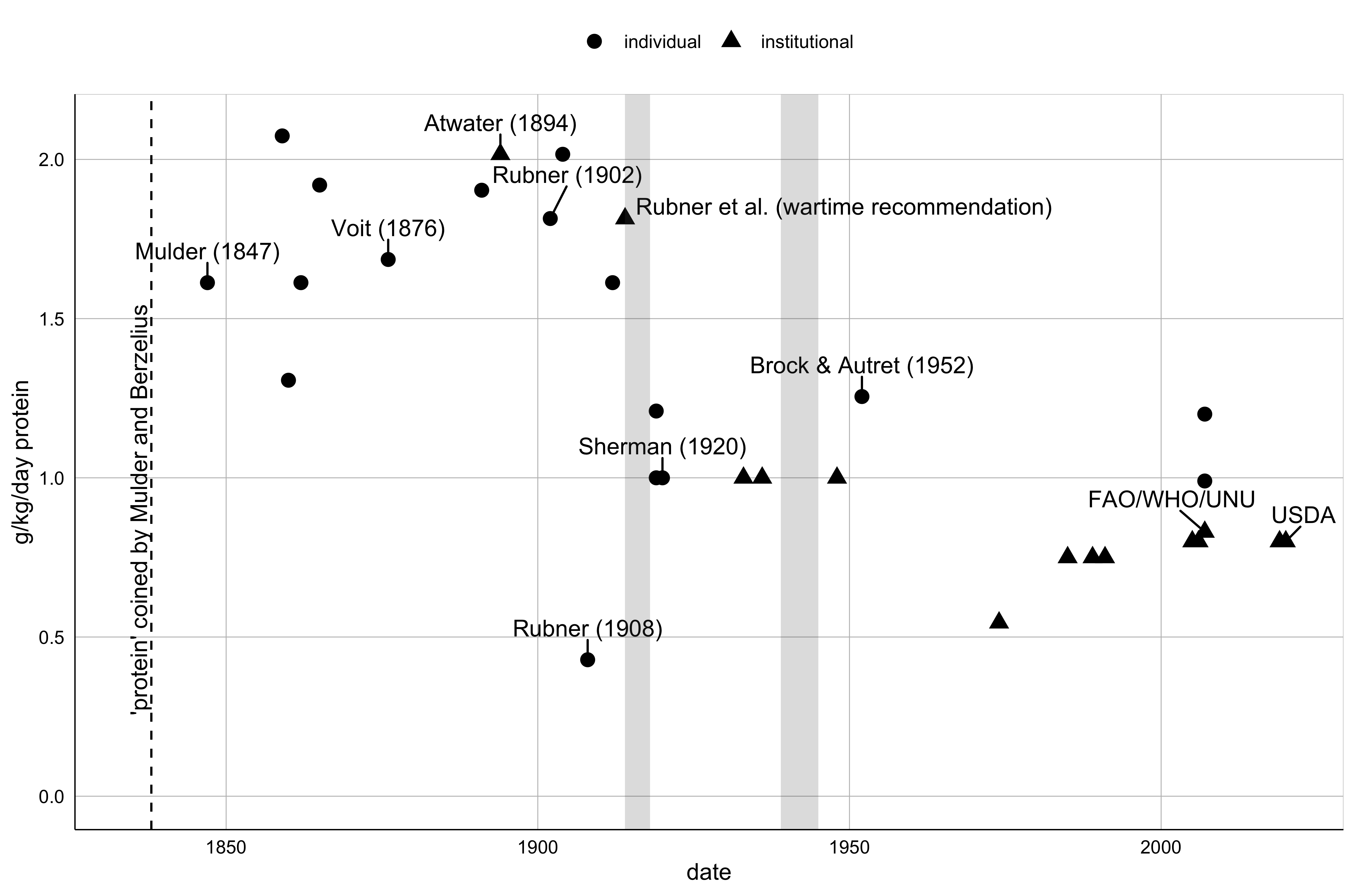

123 Halliburton,AText-BookofChemicalPhysiologyandPathology,604,608;MaxRubner,DieGesetzedesEnergieverbrauchsbeider Ernährung (Berlin u. Wien: F. Deuticke, 1902); Swan, ‘A Study of the Metabolism of a Vegetarian’; David McCay, The Protein Element

in Nutrition (London; New York: Edward Arnold; Longmans, Green & Co., 1912), 69, 110; Jules Amar, The Physiology of Industrial Organisation and the Re-Employment of the Disabled, trans. Bernard Miall (London: The Library Press Limited, 1918), https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.46478; Sherman, Gillett, and Osterberg, ‘Protein Requirement of Maintenance in Man and the Nutritive Efficiency of Bread Protein’; Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, vol. I: Interim Report of the Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition (Geneva: League of Nations Publications Department, 1936); Kenneth L. Blaxter, ‘The Purpose of Protein Production’, in The Biological Efficiency of Protein Production, ed. John Gareth Watkin Jones (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973), 4; R. Passmore et al., Handbook on Human Nutritional Requirements (Geneva: World Health Organization, 1974), 20; Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation, ‘Energy and Protein Requirements’, World Health Organization Technical Report Series (Geneva: World Health Organization, 1985), 104–5; Subcommittee on the Tenth Edition of the RDAs, Recommended Dietary Allowances (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1989), 52–66; Cannon, ‘Nutrition’; Jennifer J. Otten, Jennifer Pitzi Hellwig, and Linda D. Meyers, eds., DRI, Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements (Washington, D.C: National Academies Press, 2006); Mohammad A Humayun et al., ‘Reevaluation of the Protein Requirement in Young Men with the Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation Technique’, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 86, no. 4 (1 October 2007): 995–1002, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/86.4.995; WHO, FAO, and UNU, eds., Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation; [Geneva, 9 - 16 April 2002], WHO Technical Report Series 935 (Joint Expert Consultation on Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition, Geneva: WHO, 2007); Rajavel Elango et al., ‘Evidence That Protein Requirements Have Been Significantly Underestimated’:, Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 13, no. 1 (January 2010): 52–57, https://doi. org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e328332f9b7; Walter Willett et al., ‘Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems’, The Lancet 393, no. 10170 (February 2019): 447–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4; U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025.

Comments (0)