As a result, while some interviewees argued that investment in beef cattle could benefit small producers through making their livelihoods more diversified and resilient, increasing household incomes and improving nutritional health, most had shifted their focus towards poultry and egg production and towards the raising of cattle and small ruminants to produce dairy products(2). This pattern of financing (with the possible exception of investment in dairy production) is consistent with the Joint Multilateral Development Bank Assessment Framework for Paris Alignment for Direct Investment Operations (African Development Bank Group et al., 2021), which classifies investment in fishing, aquaculture and non-ruminant livestock agriculture as being universally aligned with the Paris Agreement’s climate change mitigation goals. As such, it may in part reflect the Framework’s influence on DFIs’ investment decision-making.

Some interviewees highlighted that these environmental concerns – combined with the emergence of new evidence about the economic and nutritional benefits of aquaculture – had also driven increased interest in investment in small-scale aquaculture projects. However, while aquaculture projects had as a result assumed an increasingly prominent role within some DFIs’ investment programmes, other interviewees suggested that they had struggled to find aquaculture projects which were large enough in scale to be investable. Some were also reluctant to finance aquaculture enterprises due to the failure of previous investments, with one interviewee highlighting that aquaculture projects could easily fall victim to disease if those involved in them were not already skilled in fish farming and did not have access to healthy breeding stock. As a result, while these investors displayed enthusiasm for investment in aquaculture, a larger proportion of their investment still appeared to be directed towards poultry, egg and dairy value chains.

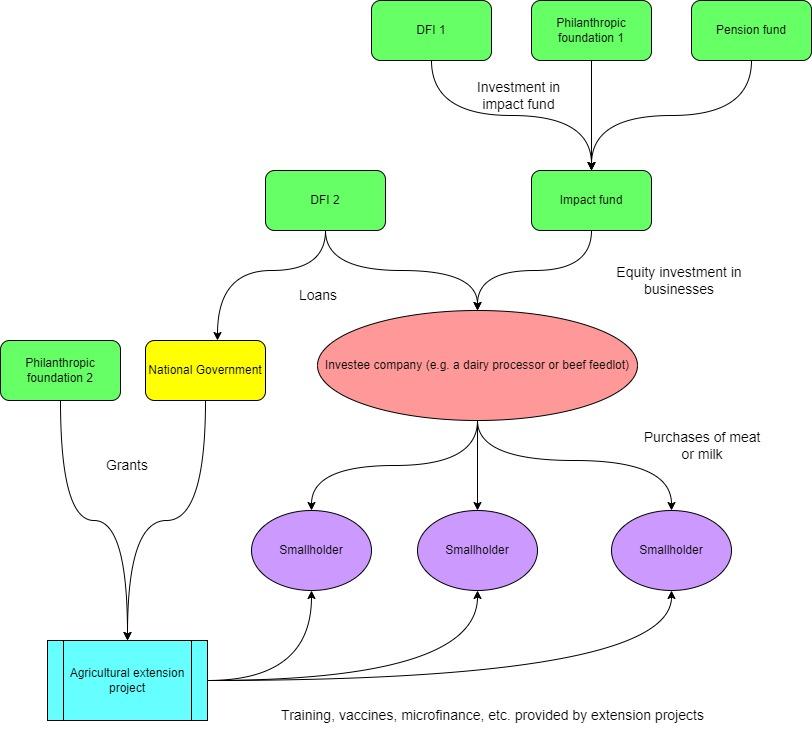

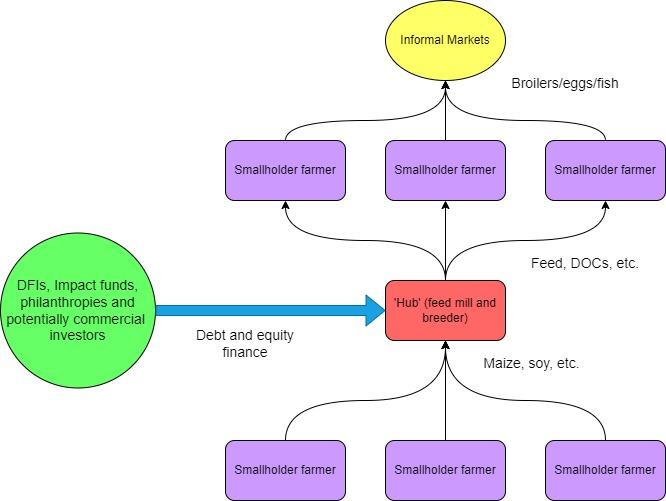

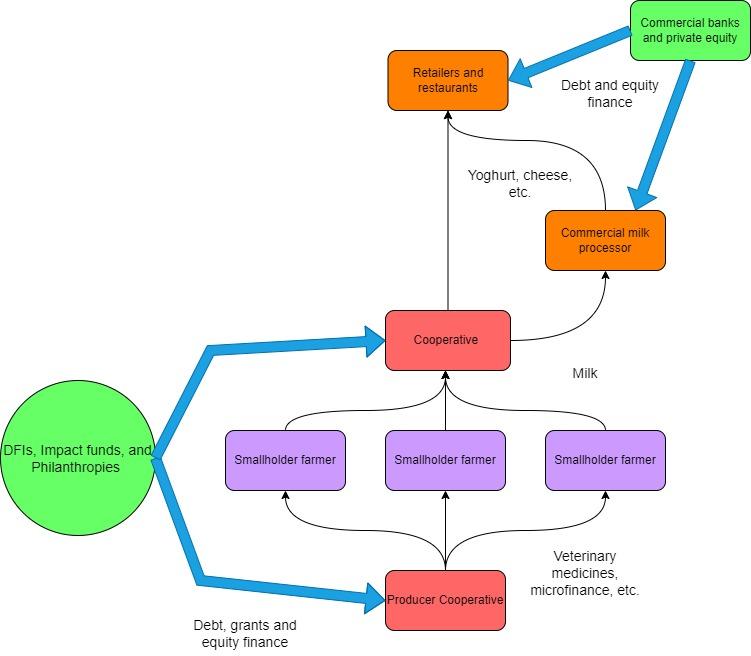

These investors’ objectives of improving the economic and nutritional wellbeing of smallholder farmers led them to focus their investments on two types of enterprises. First, most such organisations invested in companies supplying high-quality agricultural inputs such as veterinary medicines, professionally mixed animal feeds and higher yielding breeds of animals(3) in the hope that making these products more affordable and available would increase the productivity of small-scale livestock producers. Second, some invested in enterprises which purchased animals or animal products from smallholder farmers and aggregated them for sale to commercial buyers or processed them into higher value products. Investment in this second group of enterprises (described variously as aggregators, offtakers or processors) was intended to ‘connect’ small producers to more lucrative markets for processed animal products, and thus enable them to secure a higher price for their produce.

This dual emphasis on replacing domestically produced breeding stock and animal feed with commercial agricultural inputs, and on encouraging smallholders to sell their produce via food manufacturers, retailers and foodservice enterprises operating within the formal economy instead of local informal markets, situates the smallholder intensification vision firmly within the ‘value chain’ approach to agricultural development. Promoted by prominent international development actors such as the World Bank Group since the late 2000s, value chain approaches are distinguished by their belief that poverty and low productivity among smallholder farmers results from isolation from formal markets in which buyers are willing to pay higher prices for agri-food products. They thus tend to focus development institutions’ attention and investments on facilitating the inclusion of small producers into a ‘chain’ of formal enterprises – from input suppliers and processors to retailers – capable of connecting them both to manufacturers of high-quality agricultural inputs and to urban or international consumers capable of paying a higher price for their produce (McMichael, 2013).

The types of enterprises which these investors considered most vital to creating these new agricultural value chains, and thus the focus of their investments, varied between different livestock species. As Fig. 12 illustrates, investment in poultry and egg production tended to focus on companies operating feed mills (which usually sourced the crops used in their feed from local farmers), because a lack of appropriately formulated poultry feed was considered to limit the productivity of smallholders’ birds. These firms often also bred, hatched and vaccinated day-old chicks (DOCs) for sale to smallholders who then reared them for meat and/or egg production. Smallholders who purchased DOCs from these companies were expected to sell both birds reared for meat and the eggs produced by layer birds within local informal markets.

Figure 12: Destination of Smallholder Intensification investment: poultry, egg and aquaculture value chains.

Figure 13: Destination of Smallholder Intensification investment: dairy value chains.

These investors often invested deliberately in countries and companies which purely commercial investors would (as discussed in the next section) consider either too risky or insufficiently profitable to finance. In doing so, they hoped to produce a greater positive impact both through benefitting the poorest and most marginalised producers and through enabling agricultural enterprises with limited access to other sources of finance to establish themselves and expand. This imperative to maximise the ‘development impact’ of their investments did have to be balanced against the risk that projects in the most politically and economically fragile countries would fail due to conflict or political instability, a lack of reliable markets for animal products or events such as environmental shocks. However, these investors’ relatively high tolerance for risk had enabled them to apply this investment approach across much of Eastern and Southern Africa. By contrast, some interviewees had avoided investing in West and Central Africa (with the exception of larger West African markets such as Ghana and Nigeria) because they perceived many countries within these regions as presenting riskier and more challenging business environments for investors for reasons including conflict, poor governance and political instability.

Comments (0)