Footnotes

-

Erica Marie Nelson, Nicholas Nisbett, and Stuart Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition: Critical Reflections on Contested Pasts and Reimagined Futures’, BMJ Global Health 6, no. 11 (November 2021): e006337, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006337.

-

Nott, ‘“No One May Starve in the British Empire”’, 567.

-

Michael Worboys, ‘The Discovery of Colonial Malnutrition between the Wars’, in Imperial Medicine and Indigenous Societies, ed. David Arnold (Manchester University Press, 2017), https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526123664.00013; Cynthia Brantley, ‘Kikuyu-Maasai Nutrition and Colonial Science: The Orr and Gilks Study in Late 1920s Kenya Revisited’, The International Journal of African Historical Studies 30, no. 1 (1997): 49, https://doi.org/10.2307/221546; Kimura, Hidden Hunger, 22.

-

D. C. Robinson et al., ‘The Clinical and Epidemiologic Features of Tropical Ulcer (Tropical Phagedenic Ulcer)’, International Journal of Dermatology 27, no. 1 (January 1988): 49–53, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1988.tb02339.x; Stefano Veraldi et al., ‘Tropical Ulcers: The First Imported Cases and Review of the Literature’, European Journal of Dermatology 31, no. 1 (February 2021): 75–80, https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2021.3968.

-

The Maasai, though healthier and larger, were “negligible” “[a]s a labour force” because “[t]heir interest is in cattle and nothing else, and apart from engaging as herdsmen they do not enlist for work.”

-

J. L. Gilks and John Boyd Orr, ‘The Nutritional Condition of the East African Native’, The Lancet, 12 March 1927, 561.

-

Gilks and Orr, 561.

-

Gilks and Orr, 561.

-

Brantley, ‘Kikuyu-Maasai Nutrition and Colonial Science’; Nott, ‘“No One May Starve in the British Empire”’, 559.

-

Brantley, ‘Kikuyu-Maasai Nutrition and Colonial Science’, 52.

-

Dorothy L. Hodgson, ‘“Once Intrepid Warriors”: Modernity and the Production of Maasai Masculinities’, in Gendered Modernities, ed. Dorothy L. Hodgson (New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2001), 105–45, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-09944-0_5; Lotte Hughes, ‘“Beautiful Beasts” and Brave Warriors: The Longevity of a Maasai Stereotype’, in Ethnic Identity: Problems and Prospects for the Twenty-First Century, ed. Lola Romanucci-Ross, George A. De Vos, and Takeyuki Tsuda, 4th ed (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2006), 264–94.

-

Even before the famous ‘Man the Hunter’ symposium in 1966, generations of anthropologists have discussed the role of hunting and meat-eating in human evolution—in short, to what extent ‘[H]uman hunting underlies humanness.’ It is beyond the scope of this essay to go into these debates in any detail. Suffice it to say that the image of a (crucially) male human hunter is a recurring motif in both academic and popular thinking about pre-modern humans and in turn tends to shape conceptions of modern hunter-gatherers. It also undoubtedly plays a role in the primitivist strain of modern dieting culture that finds its expression in the Paleo Diet, the Carnivore Diet, and so on. Travis Rayne Pickering, Rough and Tumble: Aggression, Hunting, and Human Evolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 8; Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore, eds., Man the Hunter: The First Intensive Survey of a Single, Crucial Stage of Human Development : Man’s Once Universal Hunting Way of Life (London: Taylor and Francis, 1968); Craig B. Stanford and Henry Thomas Bunn, Meat-Eating & Human Evolution (Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press, 2001); Christine Knight, ‘Indigenous Nutrition Research and the Low-Carbohydrate Diet Movement: Explaining Obesity and Diabetes in Protein Power’, Continuum 26, no. 2 (April 2012): 289–301, https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2011.562971; Dorsa Amir, ‘A Viral Twitter Thread Reawakens the Dark History of Anthropology’, Nautilus, 21 April 2022, https://nautil.us/a-viral-twitter-thread-reawakens-the-dark-history-of-anthropology-16408/.

-

136 Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, 1936, I: Interim Report of the Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition:15; Jia-Chen Fu, ‘Confronting the Cow’, in Moral Foods: The Construction of Nutrition and Health in Modern Asia, ed. Qizi Liang and Melissa L. Caldwell, Food in Asia and the Pacific (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2019), 50.

-

J. P. W. Rivers, ‘The Profession of Nutrition—an Historical Perspective’, Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 38, no. 2 (September 1979): 228, https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS19790035.

-

Tom Scott-Smith, On an Empty Stomach: Two Hundred Years of Hunger Relief (Cornell University Press, 2020), 75–89, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501748677; Nelson, Nisbett, and Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition’, 3.

-

E. Burnet and W. R. Aykroyd, ‘Nutrition and Public Health’, League of Nations: Quarterly Bulletin of the Health Organisation, no. 4 (1935): 452; cited in Nott, ‘“No One May Starve in the British Empire”’, 560.

-

Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, 1936; Technical Commission of the Health Committee, The Problem of Nutrition, vol. II: Report on the Physiological Bases of Nutrition (Geneva: League of Nations Publications Department, 1936); Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, vol. III: Nutrition in Various Countries (Geneva: League of Nations Publications Department, 1936); Nelson, Nisbett, and Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition’.

-

Gilks and Orr, ‘The Nutritional Condition of the East African Native’, 561.

-

Food (War) Committee, Report of the Food (War) Committee of the Royal Society on the Food Requirements of Man and Their Variations According to Age, Sex, Size, and Occupation, 18 (emphasis original).

-

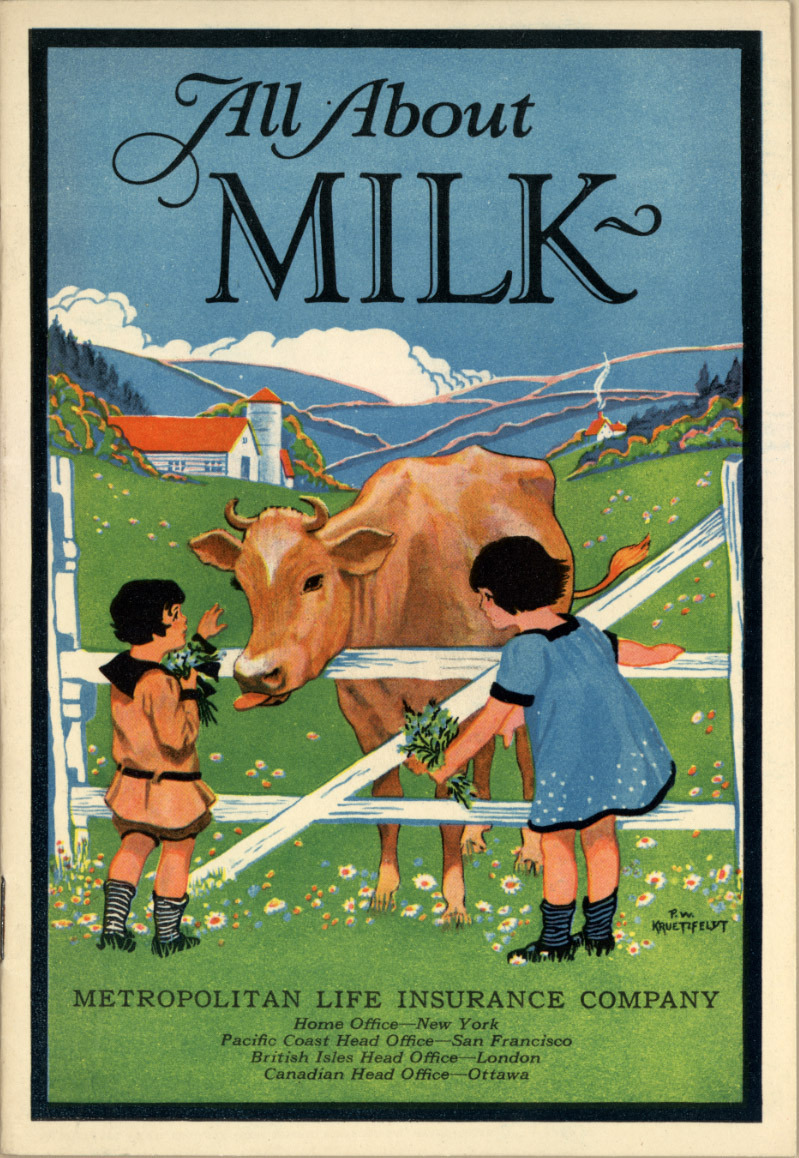

Deborah Valenze, Milk: A Local and Global History (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2011), 253–57.

-

Peter J. Atkins, ‘Fattening Children or Fattening Farmers? School Milk in Britain, 1921–1941’, The Economic History Review 58, no. 1 (2005): 61–62, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00298.x; Jon Pollock, ‘Two Controlled Trials of Supplementary Feeding of British School Children in the 1920s’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 99, no. 6 (June 2006): 323–27, https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680609900624; Valenze, Milk: A Local and Global History, 260–62; Andrea S. Wiley, Re-Imagining Milk, The Routledge Series for Creative Teaching and Learning in Anthropology (New York: Routledge, 2011), 60,77-78.

-

Whether milk consumption has a particular effect on child growth beyond infancy is a complex issue. A century after these initial claims we can say that there is weak evidence for a small effect on lean body mass but not on height, but the question is far from settled. Nevertheless, a general belief that increasing milk consumption is a good way to promote child growth (and final adult height) is probably more widespread around the world today than it was in the twentieth century, since Western cultural beliefs about food have spread along with Western eating patterns in recent decades. Clear examples of this are found in government policies to increase milk consumption by children in order to promote growth in countries like China and Thailand which have little history of dairy consumption and where drinking milk has traditionally had very different (indeed, negative) connotations. On the related question of the effect of protein intake on infant growth, we can now say, contrary to assumptions through much of the 20th century, that there is none—at least within the range of protein contents in formulae and breastmilk. Wiley, Re-Imagining Milk, 78- 84,96-102; D Joe Millward, ‘Interactions between Growth of Muscle and Stature: Mechanisms Involved and Their Nutritional Sensitivity to Dietary Protein: The Protein-Stat Revisited’, Nutrients 13, no. 3 (25 February 2021): 40–43, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030729.

-

Cannon, ‘Nutrition’; modern research is now complicating a neat equation of greater final height and better health, with, for example, higher incidence of some cancers among taller people. G. David Batty et al., ‘Height, Wealth, and Health: An Overview with New Data from Three Longitudinal Studies’, Economics & Human Biology 7, no. 2 (July 2009): 137–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2009.06.004.

-

Atkins, ‘Fattening Children or Fattening Farmers? School Milk in Britain, 1921–1941’, 64.

-

Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, 1936, I: Interim Report of the Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition:58.

-

One 1933 textbook on agriculture stated that “[a] casual look at the races of people seems to show that those using much milk are the strongest physically and mentally, and the most enduring of the people of the world”; U. P. Hedrick, A History of Agriculture in the State of New York (New York: New York Agricultural Society, 1933); cited in E. Melanie DuPuis, Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink (New York: New York University Press, 2002), 115.

-

Wiley, Re-Imagining Milk, 102–3.

-

For example, in an advert for Plasmon: ‘Nature has elaborated one food, and only one. All others are merely adaptations. This food is milk.’ The International Plasmon Ltd., ‘PLASMON’, Manchester Courier, 21 June 1901, sec. Advertisements, The British Newspaper Archive.

-

Carin Martiin, ‘Swedish Milk, a Swedish Duty: Dairy Marketing in the 1920s and 1930s’, Rural History 21, no. 2 (October 2010): 213–32,https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956793310000063.

-

DuPuis, Nature’s Perfect Food: How Milk Became America’s Drink, 117–18.

-

In an interesting example which unites the themes of milk-marketing and race, adverts by the Swedish Milk Propaganda in the 1920s and 30s often contrasted the lively and strong ‘milk-boy [mjölkpojken]’ with the weak ‘coffee-boy [kaffepojken]’. A 1934 magazine article extolling milk-drinking was illustrated with children’s drawings inspired by listening to a radio programme on health. In one, the coffee-boy has been transformed into a black boy, and the caption reads: ‘You, nigger-boy, keep your coffee! And you, Swedish girl, drink good, white milk. [Du, negerpojke, behåll du ditt Kaffe! Och du, svenska flicka, drick du den goda, vita mjölken.]’ Jenny Damberg, Nu äter vi!: de moderna favoriträtternas okända historia, 1. pocketutg (Stockholm: Ponto Pocket, 2015).

-

An example from a 1937 Swedish advert is particularly striking: “The rush of the age grips us. It forces us into an artificial way of life that will make us forget that we are yet children of nature with roots in the earth, and not mere cogs in a machine. Now more than ever we must find the power to resist in the sources of nature.” [“Tidens jäkt griper omkring sig. Den tvingar oss in i en konstlad livföring, som kommer oss at glömma, att vi trots allt äro naturens barn med rötter i jorden och icke blott kuggar i ett maskineri. Nu mer än någonsin måste vi hämta motståndskraft ur naturens källor.”] Svenska Mejeriernas Riksförening, 1937, and cf. Figure 6.

-

Atkins, ‘Fattening Children or Fattening Farmers? School Milk in Britain, 1921–1941’; A. Andresen and K. T. Elvbakken, ‘From Poor Law Society to the Welfare State: School Meals in Norway 1890s-1950s’, Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 61, no. 5 (1 May 2007): 374–77, https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.048132.

-

Technical Commission of the Health Committee, The Problem of Nutrition, II: Report on the Physiological Bases of Nutrition:15.

-

Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition, The Problem of Nutrition, 1936, I: Interim Report of the Mixed Committee on the Problem of Nutrition:58.

-

M. J. L. Dols and D. J. A. M. van Arcken, ‘Food Supply and Nutrition in the Netherlands during and Immediately after World War II’, The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 24, no. 4 (October 1946): 319, https://doi.org/10.2307/3348196.

-

Rivers, ‘The Profession of Nutrition—an Historical Perspective’, 229–30; Cannon, ‘Nutrition’, S484.

-

Valenze, Milk: A Local and Global History, 254.

-

Sherman, Gillett, and Osterberg, ‘Protein Requirement of Maintenance in Man and the Nutritive Efficiency of Bread Protein’, 106–7.

-

Robert Alexander McCance and E. M. Widdowson, ‘Old Thoughts and New Work on Breads White and Brown’, The Lancet 269 (1955): 205–10.

-

White bread was financially more profitable for commercial bakeries for several reasons: it suited their machines; had a longer shelf-life; and it allowed them to sell the bran and wheatgerm separately for use in animal feed and as an input to the production of nutritional supplements.

-

Cannon, ‘Nutrition’, S483.

-

Nelson, Nisbett, and Gillespie, ‘Historicising Global Nutrition’, 4.

-

Cannon, ‘Nutrition’; Kimura, Hidden Hunger, 23.

Comments (0)