Footnotes

33 Dana Simmons, Vital Minimum: Need, Science, and Politics in Modern France (Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

34 Simmons, 31.

35 Simmons, 55–78.

36 This was the (to the modern sensibility quasi-magical) idea that living bodies could act on the world with a special power, distinct from the physical and chemical forces that explained actions of and on objects.

37 Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure, Recherches chimiques sur la Végétation (Paris: chez la Ve. Nyon, 1804), https://archive.org/details/rechercheschimi02sausgoog.

38 R.R. van der Ploeg, W. Böhm, and M.B. Kirkham, ‘On the Origin of the Theory of Mineral Nutrition of Plants and the Law of the Minimum’, Soil Science Society of America Journal 63, no. 5 (September 1999): 1055–62, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1999.6351055x.

39 Brock, Justus von Liebig, 145–46; Humphry Davy, Elements of Agricultural Chemistry, in a Course of Lectures of the Board of Agriculture (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1813); Raphaël J. Manlay, Christian Feller, and M.J. Swift, ‘Historical Evolution of Soil Organic Matter Concepts and Their Relationships with the Fertility and Sustainability of Cropping Systems’, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 119, no. 3–4 (March 2007): 217–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2006.07.011; Christian Feller et al., ‘Soil Fertility Concepts over the Past Two Centuries: The Importance Attributed to Soil Organic Matter in Developed and Developing Countries’, Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 58, no. sup1 (October 2012): S3–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2012.693598.

40 van der Ploeg, Böhm, and Kirkham, ‘On the Origin of the Theory of Mineral Nutrition of Plants and the Law of the Minimum’.

41 Davy, Elements of Agricultural Chemistry, in a Course of Lectures of the Board of Agriculture, 274–76.

42 Justus Liebig, Organic Chemistry in Its Applications to Agriculture and Physiology, ed. Lyon Playfair (London: Taylor and Walton, 1840), 81–82.

43 Eville Gorham, ‘Biogeochemistry: Its Origins and Development’, Biogeochemistry 13, no. 3 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00002942.

44 Anthony S. Travis, ‘Agricultural Chemistry’, in Nitrogen Capture, by Anthony S. Travis (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 9–18, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68963-0_2.

45 William H. Brock, ‘Justus von Liebig. Gatekeeper of Chemistry’, Chemical Society Reviews 24, no. 6 (1995): 383, https://doi.org/10.1039/cs9952400383.

46 Justus von Liebig, ‘Some Points on Agricultural Chemistry’, Journal of the Royal Agricultural Society of England XVII, no. 1 (1856); Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 48; Brock, Justus von Liebig, 120–29.

47 Brock, Justus von Liebig, 121–22; A. J. Macdonald, ed., Rothamstead Long-Term Experiments: Guide to the Classical and Other Long- Term Experiments, Datasets and Sample Archive (Harpenden, Herts: Rothamstead Research, 2018), http://www.rothamsted.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Web_LTE%20Guidebook_2019%20Final2.pdf.

48 Cannon, ‘Nutrition’, S486.

49 Liebig, Animal Chemistry, Or Organic Chemistry in Its Applications to Physiology and Pathology, 96; Kenneth J. Carpenter, ‘The History of Enthusiasm for Protein’, The Journal of Nutrition 116, no. 7 (1 July 1986): 1365, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/116.7.1364.

50 Brock, Justus von Liebig, 187; Simmons, Vital Minimum, 16.

51 Corinna Treitel, ‘Max Rubner and the Biopolitics of Rational Nutrition’, Central European History 41, no. 1 (March 2008): 9, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008938908000022.

52 Liebig, Researches on the Chemistry of Food, 122–34.

53 Liebig, 123–24.

54 Rima Apple, ‘Science Gendered: Nutrition in the United States, 1840–1940’, Kappa Omicron Nu FORUM 10 (1997): 15.

55 The unpalatability of early attempts at freezing and tinning meat led to public concerns that meat from colonial sources was poor quality or a risk to health--although this did not stop entrepreneurs like Liebig in the long run. Rebecca J. H. Woods, ‘From Colonial Animal to Imperial Edible’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35, no. 1 (1 May 2015): 127, https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201X-2876140.

56 Cannon, ‘Nutrition’, S486.

57 an example is ‘if protein be supplied there can be no absolute need for any other but the mineral food-stuffs’; Thomas Henry Huxley and W. M. Jay Youmans, The Elements of Physiology and Hygiene; A Text-Book for Educational Institutions (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1868), 136.

58 Kenneth J. Carpenter, Alfred E. Harper, and Robert E. Olson, ‘Experiments That Changed Nutritional Thinking’, The Journal of Nutrition 127, no. 5 (1 May 1997): 1017S-1053S, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/127.5.1017S.

59 Carpenter, ‘The History of Enthusiasm for Protein’, 1986; Anson Rabinbach, The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 125–26; Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 64–76.

60 ‘Die verhängnissvolle Consequenz dieser falschen Auffassung war, dass man damals und noch längere Zeit darnach dem Eiweiss vor Allem die Aufmerksamkeit zuwandte und es als den hauptsächlichsten und wichtigsten Nahrungsstoff, ja als den einzigen betrachtete, da es allein den Verlust durch den Stoffwechsel wieder ersetzen sollte und man unter Ernähren nur den Wiederaufbau des durch die Arbeit zerstörten Gewebes verstand.’; Carl von Voit, Handbuch der Physiologie des Gesammt-Stoffwechsels und der Fortpflanzung, ed. L. Hermann, vol. Erster theil. Physiologie des allgemeinen Stoffwechsels und der Ernährung (Leipzig: F. C. W. Vogel, 1881), 339.

61 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 90–94; Treitel, ‘Max Rubner and the Biopolitics of Rational Nutrition’; Simmons, Vital Minimum, 94.

62 A. E. Harper, ‘Origin of Recommended Dietary Allowances—an Historic Overview’, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 41, no. 1(1985): 140–48, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/41.1.140.

63 Harper, 141.

64 W. B. Halliburton, A Text-Book of Chemical Physiology and Pathology (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1891), 604–5, 815–16.

65 W. O. Atwater, ‘Principles of Nutrition and Nutritive Value of Food’, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers’ Bulletin 142 (1906): 35; Harper, ‘Origin of Recommended Dietary Allowances—an Historic Overview’, 141; Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 89; Treitel, ‘Max Rubner and the Biopolitics of Rational Nutrition’, 9–13.

66 Treitel, ‘Max Rubner and the Biopolitics of Rational Nutrition’, 13.

67 Treitel, 9.

68 Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 100.

69 Atwater’s name is still familiar to students of nutrition in the context of ‘Atwater factors’, the system used to estimate the energy content of food.

70 Mikkel Hindhede, Die Neue Ernährungslehre (Dresden: Emil Pahl, 1922), 5.

71 W. O. Atwater and Chas. D. Woods, ‘Comments on the Dietary Studies at Purdue University’, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Office of Experiment Stations Bulletin 32 (1896): 23–28; Carpenter, ‘The History of Enthusiasm for Protein’, 1366; Carpenter, Protein and Energy, 106–7.

72 From a modern perspective, we do indeed expect the wealthiest groups to eat most healthily, so this might strike readers as a reasonable methodological assumption. But the point is that this is inextricably intertwined with the effects of education. Whatever the best recommendations of nutritional science in a given period, we can expect to see those recommendations followed most by the most educated—who are, not incidentally, generally the most wealthy. As a result, differences in dietary habits between social classes may tell us something about economics (the constraints of poverty), culture and access to education; if they also tell us something about instinctive responses to biological needs, that would be very difficult to unravel from these other effects.

73 Atwater, ‘Principles of Nutrition and Nutritive Value of Food’.

74 U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025, 9th Edition (USDA, 2020), 133–34, https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf; note that these are based on reference weights for adult women and men of 57kg and 70kg respectively. By contrast, the US population mean weights observed in 2015-2016 were 77.4kg for adult women and 89.8kg for adult men. Cheryl D. Fryar et al., ‘Mean Body Weight, Height, Waist Circumference, and Body Mass Index Among Adults: United States, 1999–2000 Through 2015–2016’, National Health Statistics Reports (Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 20 December 2018), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr122-508.pdf.

75 Bentley B. Gilbert, ‘Health and Politics: The British Physical Deterioration Report of 1904’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 39, no. 2 (1965): 143.

76 Inter-departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration, Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration, vol. 1 (London: Wyman & Sons, Limited, 1904), 2, 97.

77 Inter-departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration, 1:40–41, 57.

78 The distinction between a weakening of British masculinity caused by an unhealthy urban environment and a heritable ‘racial’ deterioration was made by some but more often left vague. The committee itself emphasised that they did not believe they had good enough data to draw conclusions about the ‘British race’ as a whole and so had avoided this phrase. Gilbert, ‘Health and Politics: The British Physical Deterioration Report of 1904’, 143, passim.; Inter-departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration, Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Physical Deterioration, 1:102.

79 J. Leonard Corning, Brain Exhaustion, With Some Preliminary Considerations on Cerebral Dynamics (D. Appleton and Company, 1884), 196–97.

80 David Arnold, ‘The Good, the Bad and the Toxic: Moral Foods in British India’, in Moral Foods: The Construction of Nutrition and Health in Modern Asia, ed. Qizi Liang and Melissa L. Caldwell, Food in Asia and the Pacific (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2019), 119–22.

81 Samuel Gompers and Herman Guttstadt, Meat vs. Rice; American Manhood against Asiatic Coolieism, Which Shall Survive? (San Francisco: Published by American Federation of Labor and Printed as Senate Document 137, 1902), 22, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.32106007093054.

82 Rosanne Currarino, ‘“Meat vs. Rice”: The Ideal of Manly Labor and Anti-Chinese Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century America’, Men and Masculinities 9, no. 4 (2007): 476–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X05284993; Vasile Stănescu, ‘“White Power Milk”: Milk, Dietary Racism, and the “Alt-Right”’, Animal Studies Journal 7, no. 2 (2018): 102–28; Iselin Gambert and Tobias Linné, ‘From Rice Eaters to Soy Boys: Race, Gender, and Tropes of “Plant Food Masculinity”’, Animal Studies Journal 7, no. 2 (2018): 129–79.

83 “limités ni par leur mauvaise volonté ni par leur faiblesse numérique”

84 Jules Amar, Le Rendement de la Machine humaine (Paris: Librairie J.-B. Baillière et Fils, 1910), 4, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/kby3fpqt.

85 Amar, Le Rendement de la Machine humaine; Rabinbach, The Human Motor, 186; Arnold, ‘The Good, the Bad and the Toxic: Moral Foods in British India’.

86 Atwater, ‘Principles of Nutrition and Nutritive Value of Food’, 36.

87 For example, a summary of Atwater’s 1894 article on nutrients appeared in a variety of local newspapers in the US in 1895; among other conclusions, it stated ‘we eat far too much fat and starch and sugar and too little protein.’ ‘Protein and Carbohydrates’, The Philipsburg Mail, 7 March 1895, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

88 One example is a list of foods by protein content published in US newspapers in 1917-1918. The message was directed at housewives, who were advised to identify how they could get the most protein for their money. United States Department of Agriculture, ‘Foods Which Will Provide The Most Protein At Smallest Cost’, The Adair County News, 2 January 1918, sec. Bulletins, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers.

89 Gyorgy Scrinis, ‘On the Ideology of Nutritionism’, Gastronomica 8, no. 1 (1 February 2008): 39–48, https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2008.8.1.39; Michael Pollan, In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto (New York: Penguin Press, 2008); Gyorgy Scrinis, Nutritionism: The Science and Politics of Dietary Advice, Arts and Traditions of the Table : Perspectives on Culinary History (New York, NY: Columbia Univ. Press, 2013).

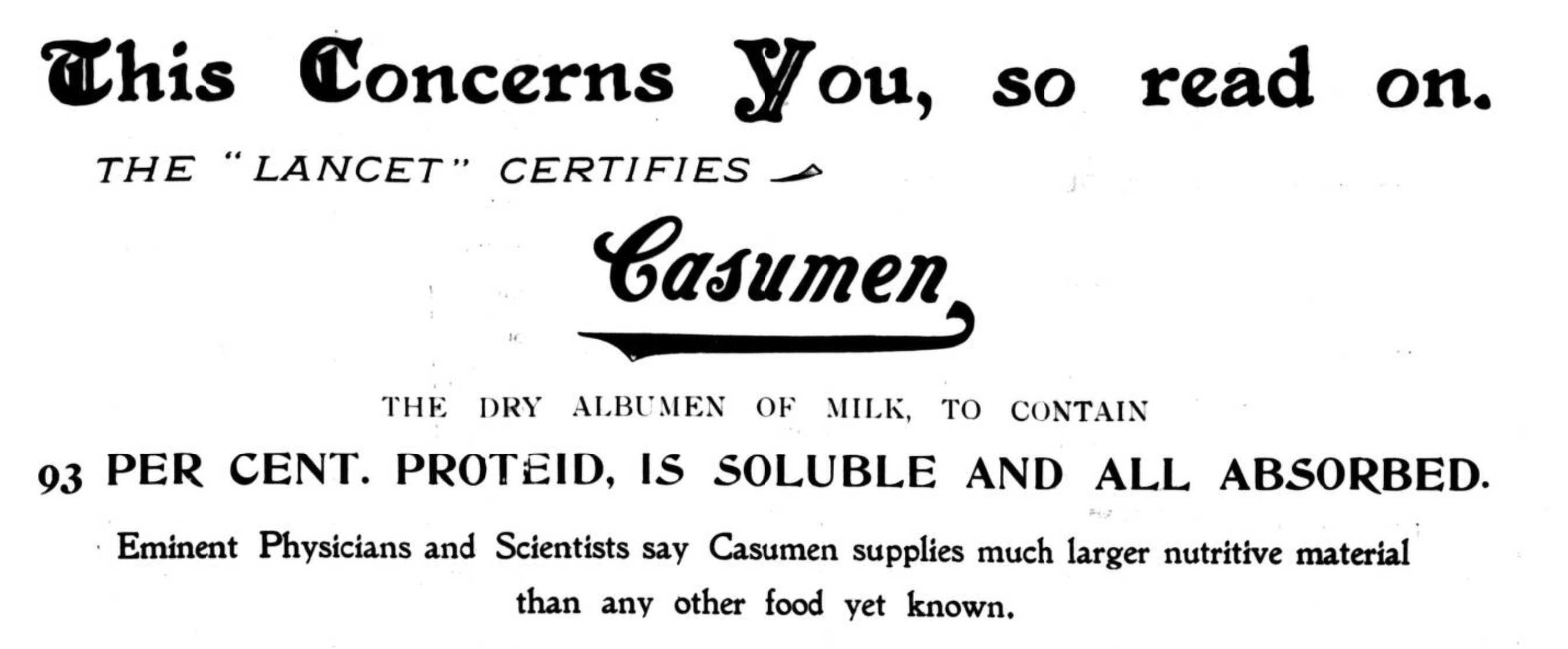

90 Conor Heffernan, ‘Superfood or Superficial? Plasmon and the Birth of the Supplement Industry’, Journal of Sport History 47, no. 3 (2020): 243–62, https://doi.org/10.1353/sph.2020.0050; Lesley Steinitz, ‘Transforming Pig’s Wash into Health Food: The Construction of Skimmed Milk Protein Powders’, Global Food History, 29 December 2021, 1–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/20549547.2021.2010977.

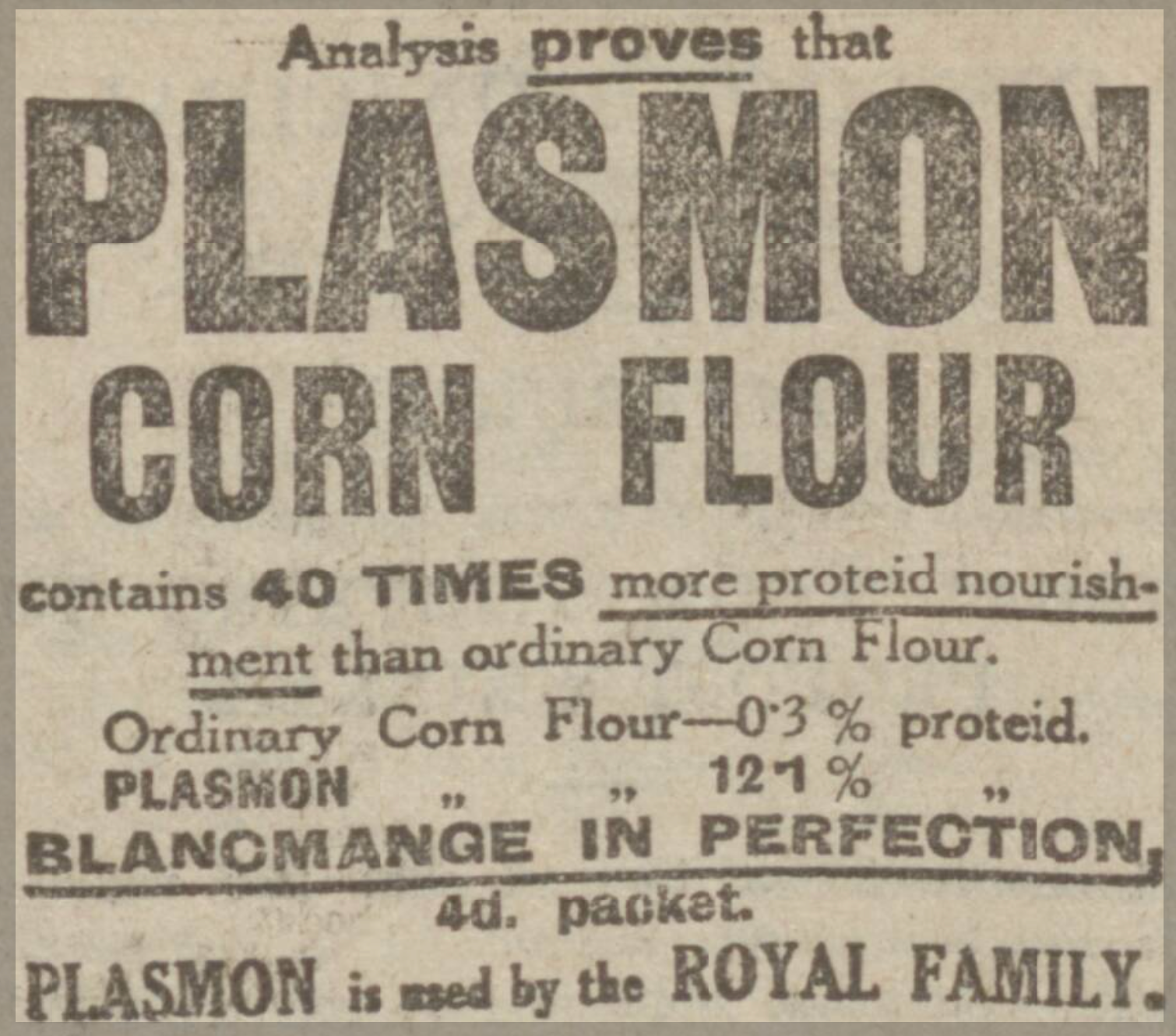

91 ‘Analysis proves that PLASMON CORN FLOUR contains 40 TIMES more proteid nourishment than ordinary Corn Flour. Ordinary Corn Flour--0.3% proteid. PLASMON 12.1%.’ The International Plasmon Ltd., ‘PLASMON CORN FLOUR’, Cornishman, 6 July 1911, sec. Advertisement and Notices, British Library Newspapers, ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2083/apps/doc/IG3223540295/BNCN?u=oxford&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=17ff06f1.

92 ‘AN ARMY SURGEON ... writes ... On “Black Monday” all our officers, twenty-three in number, carried three sticks of Plasmon Chocolate. None of us suffered the slightest, either from the heat or from the fatigue although we had breakfast at 5 30 a.m., and did not mess until 8 p.m.’ The International Plasmon Limited, ‘PLASMON CHOCOLATE’, Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser, 10 May 1901, 77, 13885 edition, sec. Advertisement and Notices, British Library Newspapers, ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2083/apps/doc/IG3220590141/BNCN?u=oxford&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=46309b46.

93 Heffernan, ‘Superfood or Superficial?’, 242,248.

94 Lauren Alex O’Hagan, ‘Flesh-Formers or Fads? Historicizing the Contemporary Protein-Enhanced Food Trend’, Food, Culture & Society, 18 June 2021, 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2021.1932118.

95 Roberta J. Park, ‘Muscles, Symmetry and Action: “Do You Measure up?” Defining Masculinity in Britain and America from the 1860s to the Early 1900s’, The International Journal of the History of Sport 24, no. 12 (December 2007): 1604–36, https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360701619022; Heffernan, ‘Superfood or Superficial?’, 249; Steinitz, ‘Transforming Pig’s Wash into Health Food’; O’Hagan, ‘Flesh-Formers or Fads?’

96 For example, in an advert for Sanatogen: ‘Four teaspoonsful of Sanatogen ... yield as much protein nutriment as three-quarters pound of lean beef. ... being wholly absorbed, its body-building power is enormous.’ Genatosan, Limited, ‘The Remarkable Food Value of SANATOGEN: The Genuine Food Tonic’, Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 3 January 1920, sec. Advertisements, The British Newspaper Archive.

97 Heffernan, ‘Superfood or Superficial?’, 251–52.

98 Heffernan, 253–55; For the links (perceived and actual) between the women’s suffrage movement and vegetarianism, see Elsa Richardson, ‘Cranks, Clerks, and Suffragettes: The Vegetarian Restaurant in British Culture and Fiction 1880–1914’, Literature and Medicine 39, no. 1 (2021): 133–53, https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2021.0010.

Comments (0)