Christina O’Sullivan is the Campaign & Communications Manager at Feedback, where she manages the ‘Fishy Business’ campaign. Feedback is a campaign group working to regenerate nature by transforming the food system. Christina has an MSc in Food Policy from the Centre for Food Policy, City University. She has worked at the Cornell Food and Brand Lab and the Global Centre for Food Systems Innovation at Michigan State University.

Image: RitaE, Mussels Mussel Seafood, Pixabay, Pixabay Licence

We are often told ‘you are what you eat’, but what about the food fed to the animals we eat? There has been increased scrutiny of feed for terrestrial livestock such as cows and pigs. For example, Marks & Spencer recently announced that they are removing soya from the feed in their dairy supply chain to tackle deforestation. However, less attention has been paid to what the fish on our plates is fed. Through discussing our ‘Fishy Business’ campaign I have found that most people remain unaware that the salmon in their fish supper is fed wild-caught fish from across the world. In this blog post, I discuss the findings of Feedback’s two recent reports on the fish sector, published June 2020: Off the Menu and On the Hook.

Fed aquaculture’s reliance on wild-caught fish

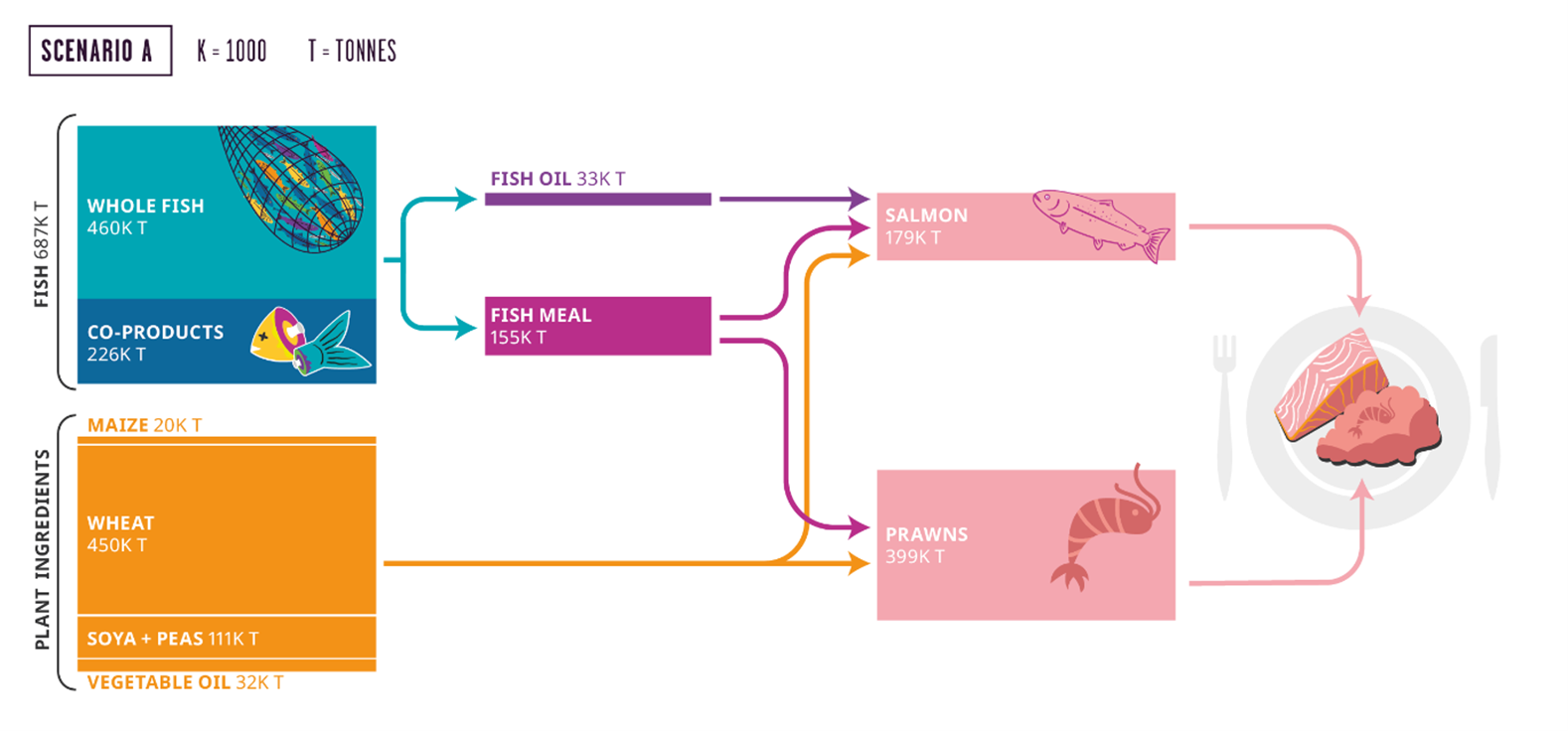

Aquaculture (fish farming) has increased in scale drastically over the past decades and currently provides approximately half the world’s seafood consumption. Salmon aquaculture is heavily reliant on wild-caught “forage fish” (for more details, see my 2019 blog post Can we have our farmed salmon and eat it too?). In Feedback’s first report on aquaculture, we calculated that the current quantity of wild fish fed to farmed Scottish salmon, 460,000 tonnes, is roughly equivalent to the amount of seafood (both wild and farmed) purchased by the entire UK population. The diagram of Scenario A, below, show how the Scottish salmon aquaculture industry currently works.

Scenario A: How the Scottish salmon aquaculture industry currently works

What if we ate like salmon? Exploring the nutritional output of eating forage fish

Our latest research (two reports: Off the Menu and On the Hook) explored whether we could obtain the same nutrients by eating the wild fish that is fed to salmon ourselves. In short, what if we ate like salmon? To investigate this, we used the Scottish farmed salmon industry as a case study.

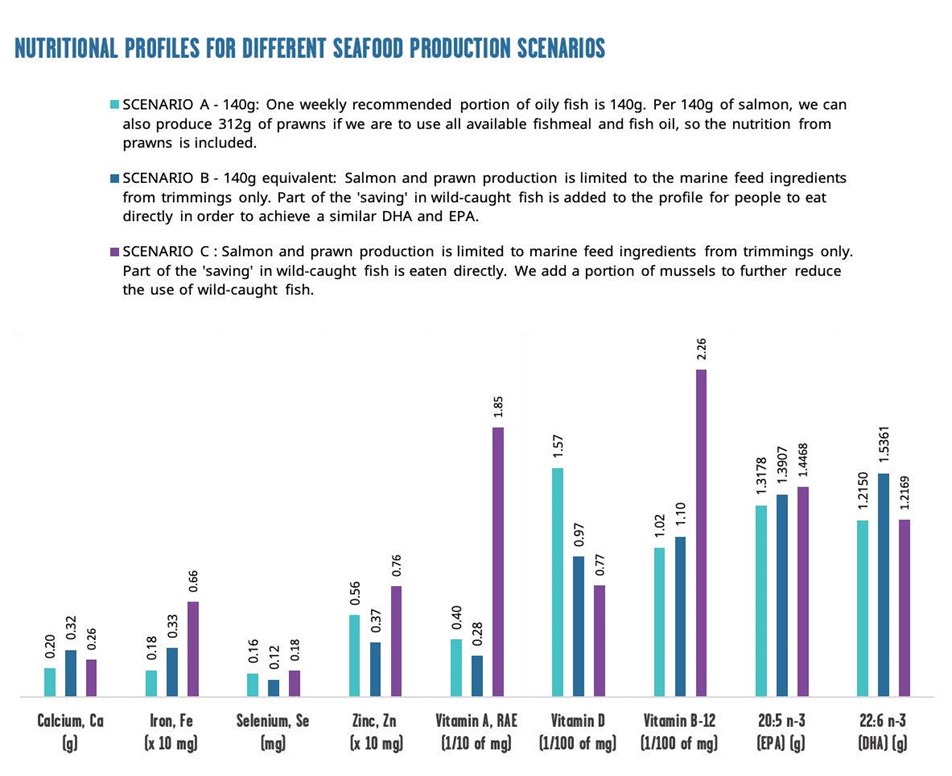

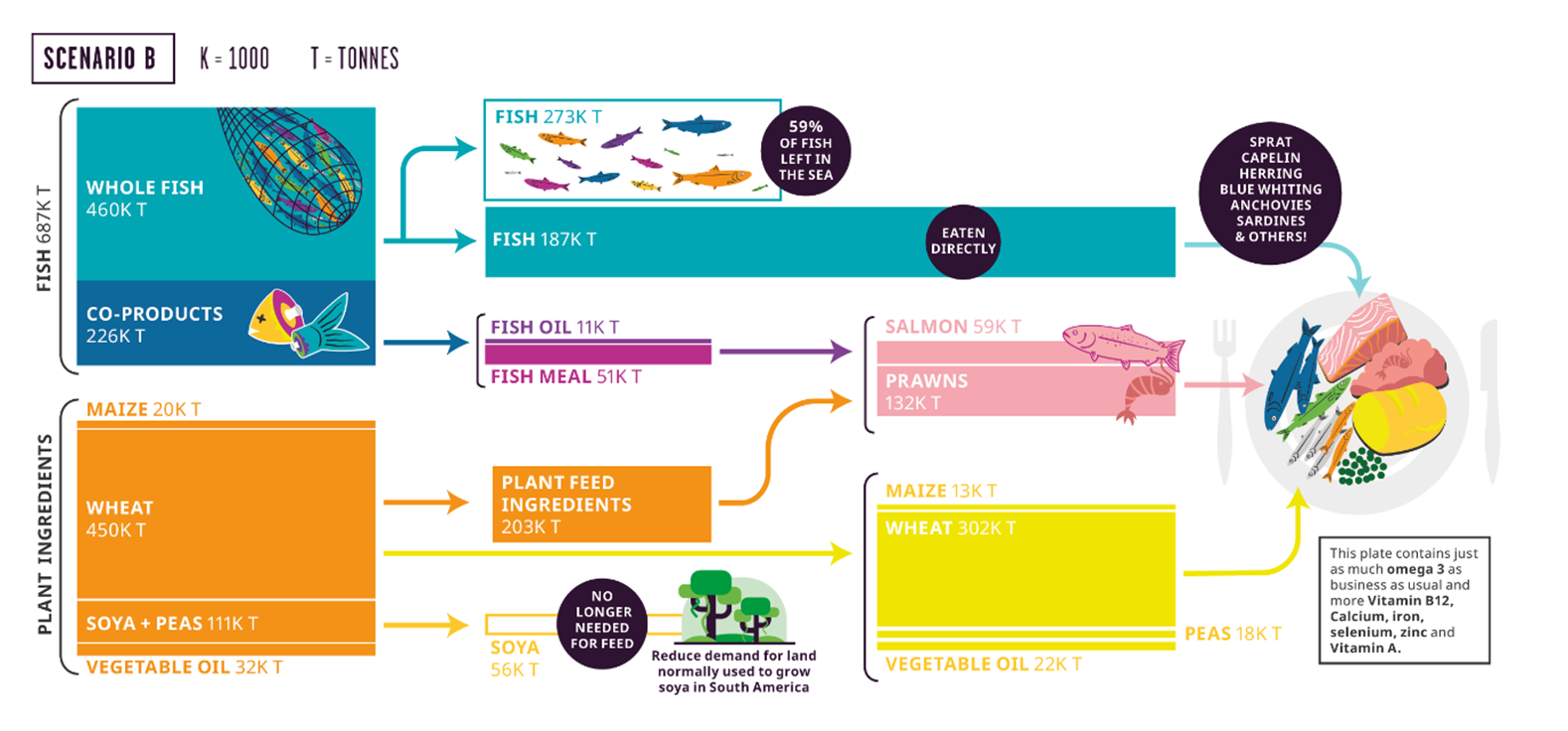

We developed Scenario B (illustrated below) in which Scottish salmon is only produced using fish oil made from trimmings from wild fish, including heads and tails. Around one third of fish oil currently used comes from trimmings, so we assumed the industry would shrink to around one third of its current production. We then estimated the quantity of wild fish that would be needed to top up the micronutrient intake of humans to the same level as we reached under the current levels of Scottish salmon production, using nutritional data for the wild fish most commonly used in feed (see the figure below).

In Scenario B, you get much less farmed salmon and prawns, as well as lower levels of plant ingredients used in their feed. The reason we factored in farmed prawn production is because farming salmon requires more fish oil than fishmeal, but fishmeal is a by-product of fish oil production. In short, farmed salmon need more oil than meal and we have assumed that the leftover meal is used by other industries, in this case prawns, instead of being wasted.

We top up our micronutrient intake with around 187,000 tonnes of wild fish that was previously being used in feed, including species such as sprat, herring and anchovy. This results in a varied plate of seafood, and around 59% of the forage fish that would have been caught in the business as usual scenario are instead left in the sea. In other words, a more diverse seafood diet, including a greater variety of wild fish plus smaller farmed salmon production, delivers a good level of micronutrients while lessening pressure on wild fish populations.

Scenario B: Scottish salmon aquaculture is fed only on oil from fish trimmings

Musseling in on the action

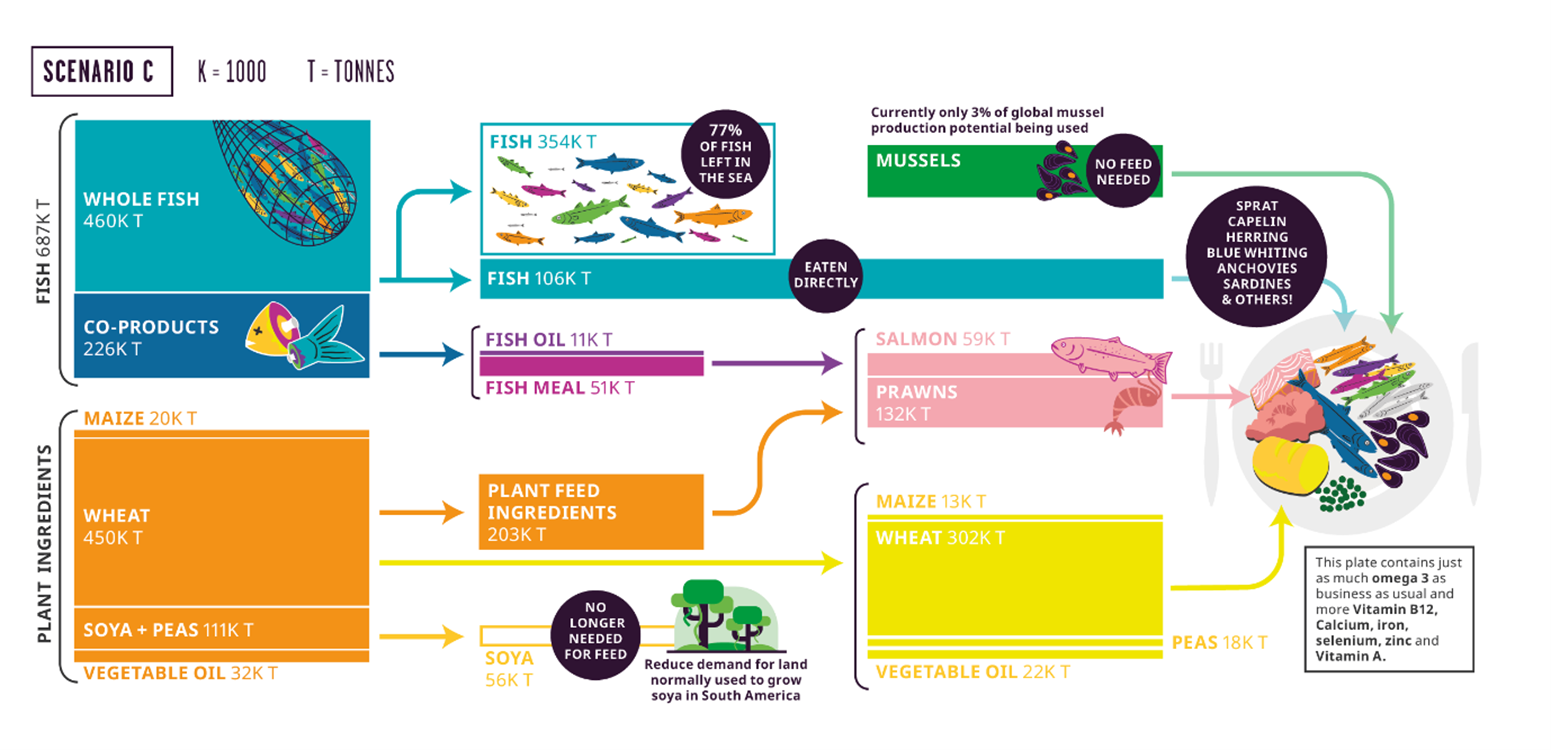

We developed Scenario C to include nutrients from unfed aquaculture. Unfed aquaculture can produce mussels and other shellfish without using external feed inputs. In this scenario we again assumed that Scottish salmon farming is constrained to feed from trimming.

Scenario C provided the same level of micronutrients as business as usual, while leaving up to 77% of wild fish currently caught for feed in the sea, because of the extra nutrients delivered by farmed mussels.

Scenario C: Adding mussels from unfed aquaculture to the human diet

I know this is a little complicated (I got very well acquainted with my scientific calculator while working on this modelling) – so we created a short animation to showcase the findings.

But will anyone eat anchovies and herring?

As I discussed in my 2019 blog post, the fish industry usually uses terms such as “unmarketable” fish, “trash” fish or “low consumer preference fish” to refer to certain species, despite examples showing that consumer preferences can be heavily influenced by marketing or celebrity chefs. My impression from discussions with industry is that they frequently use binary thinking – essentially presupposing that individuals want to eat salmon so the only options are the unsustainable status quo (my words, not theirs) or to make marginal gains in making farmed salmon more sustainable.

This way of thinking is further illustrated with the somewhat unimaginative approach to excess meat consumption being to produce vegan burgers as opposed to encouraging people to eat a variety of vegetables and pulses. I believe this is a false dichotomy and rooted in our current food system’s monocultural approach to food production. Our research suggests that the key to a sustainable seafood diet is variety and this is in line with NHS advice:

“To ensure there are enough fish and shellfish to eat, choose from as wide a range of these foods as possible. If we eat only a few kinds of fish, then numbers of these fish can fall very low due to overfishing of these stocks.”

Nutrients for whom?

Under the status quo, essential nutrients from seafood are transferred around the globe to aid the expansion of fed aquaculture, in the process removing them from more local supply chains and redirecting them towards international supply chains where they can deliver greater financial value. Both industrial fishers and local fishermen catch fish to be turned into fishmeal and fish oil, as often it is more profitable than selling to local supply chains. From a global food security perspective this does not represent a good use of nutrients.

A startling paper on fisheries from a global food security and equity perspective, published in the journal Nature, discussed the role global fisheries could play in tackling micronutrient deficiencies. The authors argued that in several countries in which nutrient intakes are inadequate, a fraction of local and regional fisheries catches could meet or exceed the dietary requirements of populations living within 100km of the coast. In these countries, a small fraction of the available production from fisheries has the potential to close nutrient gaps. For example, the dietary risk of iron deficiency in Namibia is severe (47%, measured at the country level); however, the dietary iron requirements of the coastal population in Namibia could be met by a mere 9% of the fish caught in Namibia’s exclusive economic zone.

A recent paper argues that treating fish as a public health asset can strengthen food security in low income countries. The paper highlights that the local potential is threated by over-fishing, climate change and international trade. The growth of fed aquaculture exacerbates these issues and in its current form perpetuates an inequitable seafood supply chain. In essence, we take fish from one part of the world where they could be eaten by local people, to feed them to farmed salmon intended for a much wealthier global market.

Re-framing the fish debate: paramount to question what fish and who is eating it

Our research re-frames debates concerning whether or not to eat fish and shows there is enough fish in the sea if marine resources are sustainably managed. Going beyond the question ‘should we eat farmed salmon?’ we get a richer, more diverse scenario which could deliver a varied diet for human nutrition, more fish in the sea and a healthy prognosis for our ocean. When I started my Food Policy Masters, I was introduced to the phrase ‘Wicked Problem’: a problem where multiple interdependencies mean that an attempt to solve one aspect of the problem may exacerbate others. Eating fish was highlighted as the one of the most contentious wicked problems in food policy – fish is good for us, but we do not want to strip the oceans bare. I believe to tackle this wicked problem we need to think beyond the box to find the answers to what an equitable and sustainable seafood supply chain could look like. I do not believe it lies in mass expansion of farmed salmon but instead in diversifying our fish diet. It turns out there may be plenty of fish in the sea if we are willing to try them.

Full reports:

Off the Menu: The Scottish salmon industry’s failure to deliver sustainable nutrition

There is a recording of a webinar we delivered on these reports available here.

To join the conversation, send a message to Table's Google Group (join here).

Comments (0)