These ethical and environmental goals appeared to be the main reason why these ‘vegan venture capitalists’ had chosen (unlike most of their peers) to invest in African food technology companies. The co-founder of one African startup producing plant-based meat highlighted that such companies tended to fall into a funding gap lying between two distinct groups of investors. African banks and private equity funds tended to refrain from investing in alternative protein companies because they regarded them as being excessively risky investments. Meanwhile, most of the European and North American venture capital and private equity funds which had financed alternative protein startups in their home markets tended (as discussed previously) to regard sub-Saharan Africa as an unacceptably risky location in which to invest. It therefore appeared that these ‘vegan venture capitalists’ were motivated to invest in African alternative protein startups because they regarded the transformation of diets and food systems in the world’s most rapidly growing markets for protein away from meat and dairy as being a sufficiently important normative goal to override the risk of financial loss.

These ‘vegan venture capitalists’ appear to be the only significant source of investment to which African producers (or aspiring producers) of alternative protein products currently have access. One interviewee considered this an important constraint on his firm’s growth potential because it restricted him to a narrow pool of potential investors, most of whom had only relatively small sums of capital available to invest (with each venture capitalist typically contributing a sum in the tens to the low hundreds of thousands of US dollars).

What and where?

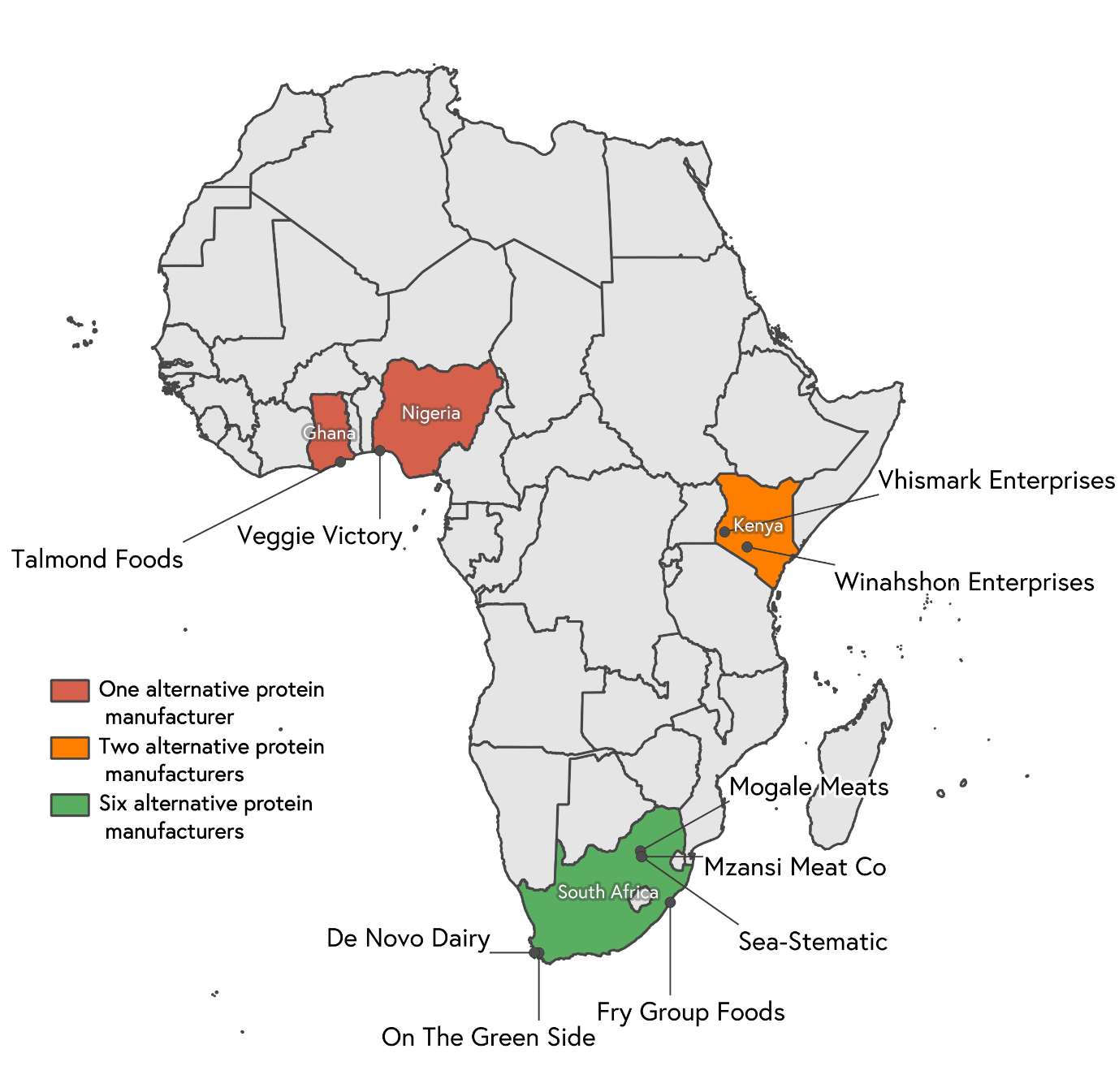

These investors typically did not finance any form of animal protein production (including aquaculture), and instead invested exclusively in startup firms producing alternative proteins. In order to assess the likely geographical focus of their investments, the author analysed the databases of alternative protein manufacturers maintained by the Good Food Institute and Crunchbase in order to establish how many such firms were active in sub-Saharan Africa and where they were headquartered(4). This analysis identified ten alternative protein producers as being active in sub-Saharan Africa. Six of these firms were located in South Africa, two were headquartered in Kenya, one was based in Nigeria and one was in Ghana. As such, it seems likely (as Fig. 14 illustrates) that investments made by these ‘vegan venture capitalists’ will display a high degree of geographical concentration around the financial and technology hubs of South Africa.

There was little evidence that this group of investors was actively financing other elements of the wider value chains which might support these alternative protein manufacturers – for instance farmers growing protein crops such as legumes or restaurants and retailers which might stock their products. Perhaps as a result, even African producers of more technologically proven alternative proteins such as plant-based meats currently appear to be operating on a relatively small scale and are predominantly targeting their products at urban consumers motivated by anxieties about health and food safety in relation to animal protein. One interviewee also noted that the fragmentation of the restaurant and food retail sectors in many sub-Saharan African counties – and their limited distribution infrastructures for chilled and frozen products – makes expansion into new regions and countries difficult and further constrains their ability to scale up production.

Figure 14: Map of alternative protein manufacturers within sub-Saharan Africa. Data source: Good Food Institute and Crunchbase.

How?

These investors’ theory of change could be summarised as follows. Adherents to the protein diversification vision expect population growth and economic expansion to drive a rapid increase in demand for protein in sub-Saharan Africa over the coming decades. While voluntary adoption of vegetarian and vegan diets is currently rare within the region, they believe that the environmental impacts of livestock agriculture mean that it will not be possible to satisfy future demand for protein sustainably by increasing production of animal products. They also observe that high rates of poverty mean that many people’s decisions about which foods to purchase and consume are acutely price-sensitive. As a result, these investors believe that if alternative protein producers can sell their products at a price similar to or lower than that of animal products then a substantial proportion of sub-Saharan African citizens may choose to augment their consumption of animal proteins with plant-based, in vitro, insect-based or fermented alternatives. They therefore hope that African consumers on constrained budgets might be persuaded to supplement their intake of animal products with price-competitive or cheaper alternative proteins.

Comments (0)