As both a proud dairy farmer from Cumbria and a student of Environmental Science at the University of Manchester, it is easy to see why I feel somewhat torn over the current state of our food system in the UK. Professors and academics tell me how ruminants perturb the natural carbon cycle, contribute to the decline in biodiversity, and graze on what could be prime wildlife habitat, but at the same time I know from lived experience that my family’s business produces nutritious milk and meat from healthy cows. These are not, of course, mutually exclusive facts. I am deeply unconvinced by each side of an increasingly polarised food debate between agro-industrialists calling for food security and intensive production on one side, and ecomodernists proposing alternative foods and abandoning the land on the other. It's clear, though, that continuing to farm the way we do is not an option. Report after report outlines not only the ecological and environmental harms and self-harm that post-war agriculture has wrought on the British countryside, but also on its people. In the last 45 years the agricultural workforce has declined by nearly a third, and the average age of a farmer in the UK creeps towards 60 due to barriers such as high land prices and inflexible tenancies which discourage new entrants (Edwards, 2021; Office for National Statistics, 2024).

I live in this agro-industrialist model of farming and can see that it is leaving the land and its community ailing; but I find the proposed alternatives just as unviable and unattractive. Instead of working to appease either position, I believe we should reject them and the divisions they stoke with an aim of striking a measured balance, embracing agricultural practices that work within natural systems while still producing a healthy quantity of valuable and nutritious food. Regenerative agriculture is the farming model that, for me, has the potential to achieve that balance, pushing back against the wholly extractive agro-industrial model we are currently stuck in, while still respecting the heritage of land management. In a way, regenerative agriculture works to heal the divide I, and I’m sure others, feel between being a farmer who cares deeply for the land, and a naturalist and academic who knows the damage that our current food system is doing to the environment. By comparing my family farm with our Cumbrian neighbours’ in this essay, I consider how regenerative farming can work in reality, and how it resists the polarised debates that delay the transition to a food system fit for the future.

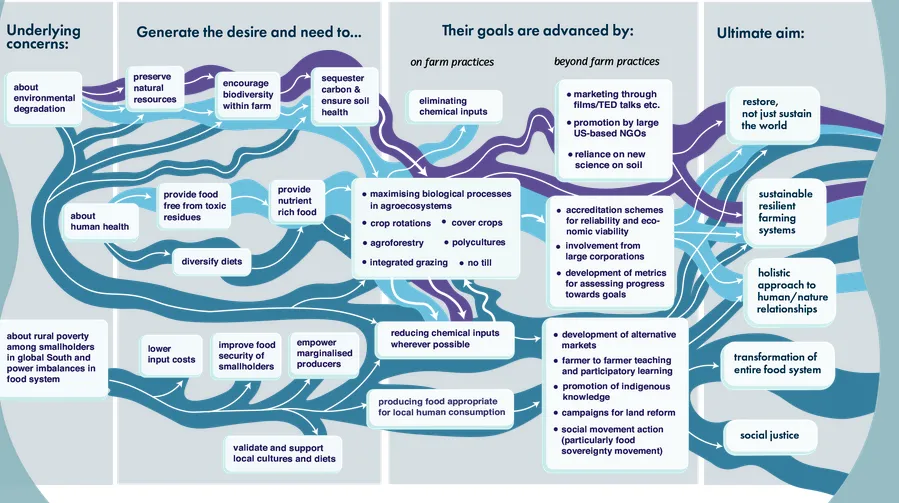

Regenerative agriculture is not a strict model of farming, it is inherently dynamic and context-driven, allowing it to be adapted to each farm and farmer; as such it has accrued a range of definitions and explanations (Miller, 2022). To me, this farming model involves producing the food, fibre and produce we need using principles and methods that work with and restore the natural systems that have been badly degraded by current approaches. Regenerative agriculture is fundamentally based around sustainable cycles; not disrupting the functioning of soil, water and biological systems by carrying out the agro-industrialist’s intensive farming practices, like artificial fertiliser and pesticide applications, nor by funnelling energy and resources into the similarly industrialised vision of processed bacterial protein.

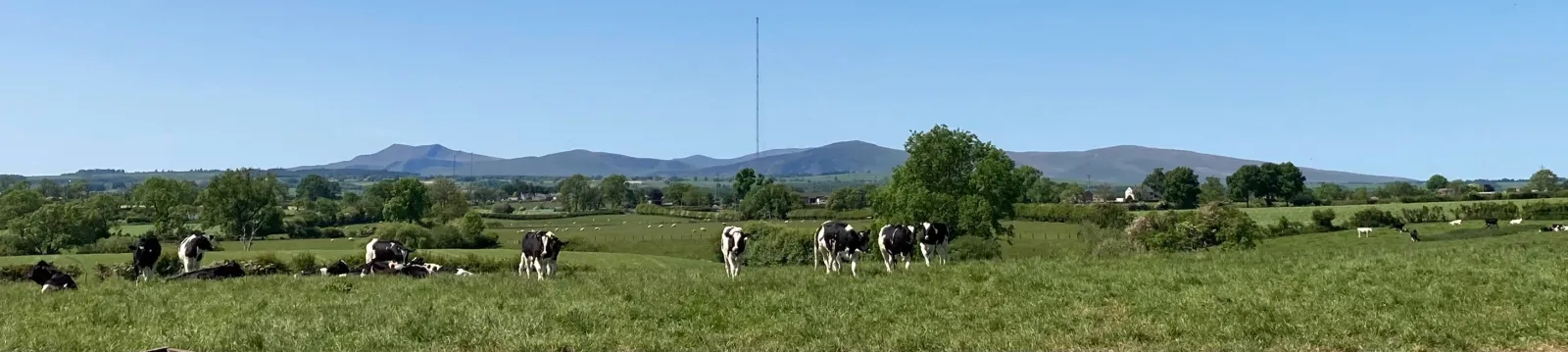

A cow awaiting milking in a dairy operation in the UK. Photo by Alexander Turner.

What I find some definitions miss, however, is the necessity of a sound business model for regenerative farming to succeed. We live and work in a capitalist world where food is a private good (Helm, 2022), and farmers and landowners who are pivoting their intensive, production-oriented businesses towards more natural systems must still be able to financially support themselves, their families and communities. Some find a conflict here between food production and nature restoration, consequently finding that regenerative agriculture, in attempting to reconcile them, must fail. While gross profit and yield may decrease during an intensive-to-regen transition, a business’ net profit, and therefore overall profitability, can increase as the three core inputs - bought-in feed, artificial fertiliser and fuel - are reduced (Nature Friendly Farming Network, 2020; Wildlife Trusts and Nature Friendly Farming Network, 2023). Nonetheless, the wider food system is stacked against those farmers wishing to start such a transition. Supermarkets (and by proxy us as consumers) expect food to be on the shelves, so shifting to a farming model with lower yields may jeopardise the minimum supply contracts farmers are often signed up to. Similarly, feed and fertiliser suppliers offer farmers long-term contracts in which prices are often lower than purchase in an on-the-spot market. Although this keep costs down and mitigates the volatility of market prices (which allowed our farm to weather disruptions such as the tripling of fertiliser price in on-the-spot markets as a result of the war in Ukraine), this system can keep farmers locked-in to their current model for months and sometimes years in advance, which in turn delays their ability to transition away from these inputs. On top of these external pressures, the often-smothering status quo enforcement from tight-knit farming families and communities can contribute to our present debilitating situation. Breaking from ‘the ways things are done’ is a daunting task for any farmer. I know from arguments with my own family that just agreeing to tinker around the edges can feel like a Herculean effort, so getting the necessary consensus to alter how a whole business operates is an even greater challenge that sadly hinders a successful regenerative transition.

But what of those that have begun to break with the status quo? My home county of Cumbria is host to many incredible farmers working a diverse range of systems, with some further down their regenerative journeys than others. Compare my family farm, situated on the banks of the River Petteril in the Eden Valley of North Cumbria, with Strickley Farm, headed by James Robinson, in the Lune Valley of South Cumbria. At almost identical elevations, with similar annual rainfalls and soil types, our contexts are not that different, and yet we pursue diverging business strategies. My family farm focuses on increasing production: we are paid per litre of milk, so it seems only natural to pursue higher yielding cows to maximise our returns. To do so, we sing from the agro-industrialist hymn book: we sow artificial fertilisers that deliver higher grass production for summer grazing and winter silage, grow pesticide-treated maize and barley crops in annually ploughed fields, and buy in feed from as far afield as Canada and Indonesia to support high milk yields. This intensive management system is profitable and ensures we can comfortably support family and staff. Meanwhile, Strickley farms organically and regeneratively; this means no artificial fertilisers or pesticides are used, with the only nutrients the soils receive coming from that returned by the cows in their slurry and manure. Pests are managed with ecology in mind - for example, without pesticides, green dock beetle populations that graze on dock plants have skyrocketed, providing natural pest management (Higgins, 2023).

Comments (0)