1. Introduction

The concept of food sovereignty was made popular in the 1990s by rural social movements, who promoted it as an alternative to the concept of food security in order to draw attention to the inequalities of the food system and the struggles of small-scale farmers. While definitions of food sovereignty are multiple and constantly changing, the idea has been embraced by an array of actors as a banner for social justice and food system transformation. The concept has grown beyond its original base amongst peasants in the global South and small-scale family farmers in the global North to unite consumers, farm and food workers, academics and food justice advocates around the world.

This coalition of different actors that have united around the concept of food sovereignty (referred to here as the food sovereignty movement [FSM]) has played a key role in criticising, amongst other things, the growing dominance of industrial agricultural practices, the increasing power of corporations in the global food system, and the convergence of diets towards more imported and processed foods. They have called for radical changes to agri-food systems, in favour of agroecological, localised and democratic methods of production and exchange.

The FSM, however, is highly diverse and heterogeneous, composed of multiple sub-groups, each representing a different set of interests and historical, cultural, and geographic contexts. In practice, the FSM therefore tends to avoid defining specific visions of food sovereignty too strictly, and instead encourages members to adopt context-specific solutions based on a set of shared principles. This approach, however, can raise questions about what food sovereignty actually means, what a food system based on its principles might look like, and what specific actions might help achieve it. This explainer will explore the historical context and evolving definitions of food sovereignty, before discussing some of these ambiguities.

2. What is food sovereignty?

The concept of food sovereignty has evolved and developed alongside the food sovereignty movement (FSM) itself, in response to the changing political, economic and ecological context of the 1990s and early 2000s. Here ‘sovereignty’ is used to draw attention to the distribution of authority and power in the food system.

2.1 Brief historical background

The end of World War II marked the reshaping of global political, economic and trade relations, and the development and widespread promotion of industrial agriculture. In response to an expanding population, a recovering global economy, and fear of socialist revolution in Mexico and Southeast Asia, the United States, with the support of other national governments, led what is known as the Green Revolution, aiming to increase global food production by increasingly mechanising agriculture and breeding higher-yielding varieties of maize, wheat and rice. The adoption of these technologies, seeds, fertilisers and pesticides was encouraged by policy makers, research institutes and emerging industries fabricating these products on a global scale from the mid-1960s, alongside the development and expansion of markets across the food supply chain from farm inputs to food products.

The FSM arose in opposition to the perceived negative social and ecological impacts of the Green Revolution and accompanying trade liberalization and structural adjustment policies (SAPs). Although the Green Revolution increased agricultural yields and improved total food supplies in some parts of Asia and Latin America, in many cases, it did not effectively tackle hunger and malnutrition, particularly amongst more marginalised portions of the world’s population., Moreover, it was primarily larger farmers who were able to take advantage of new technologies and increase their productivity., As various countries, particularly in Latin America, Africa, and S and SE Asia, shifted support towards large scale export-oriented markets and removed access to subsidized credit and technical assistance, many smallholder farmers struggled to compete with large-scale capital-intensive agriculture in global markets flooded with subsidised products from industrialised countries.

In the face of increasingly globalised trade and agriculture systems and diminishing state support, many peasant organisations looked for new ways of organising, turning to transnational cooperation with other rural social movements in order to increase their influence. In Latin America, India, Europe and North America, peasants and family farmers formed alliances and began to organise on a large scale throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s to defend their rights and protest against the changes to global agricultural trade being made during the Uruguay Round of GATT negotiations. In 1993, these various groups cemented their collective efforts, forming La Via Campesina (LVC), an international peasant organisation that has grown to encompass 200 million people across 81 nations in 2021. LVC has played a major role in defining and publicizing food sovereignty, using it as a framework that both unites and recognizes the diversity of rural, and more recently urban, people from varying social, economic, cultural, and geographical backgrounds.

2.2 The evolving definitions and membership of food sovereignty

While there is some debate among researchers about the exact origins of the concept of food sovereignty, it is generally accepted that it was popularised and promoted for the first time on the global stage by LVC at the FAO-sponsored World Food Summit in 1996. Food sovereignty was then defined as ‘the right of each nation to maintain and develop its own capacity to produce its basic foods, respecting cultural and productive diversity’.

This initial definition reflected the priorities of the rural social movements involved in its promotion at the time. These groups were primarily based in the global South and were focused on supporting smallholder farmers producing staple crops. By associating food sovereignty with the ‘nation’ they sought to restore power to the state and return to food and agricultural policies that supported peasant food production for domestic consumption and strengthened peasant livelihoods.

The NGO (Non-Governmental Organisations)/CSO (Civil Society Organisations) Forums that ran parallel to the FAO World Food Summits of 1996 and 2002 served as important sites for the growth of the FSM. The committee planning these events recognised the need to engage with a more diverse array of constituencies, and therefore used quotas and funding to ensure the participation of social movements and groups from the global South. These spaces allowed the idea of food sovereignty to travel beyond LVC and its initial base of peasant and family farmers: at these events it became a unifying concept for various CSOs and NGOs seeking to challenge the FAO’s food security framework (as we discuss in more detail below), and was taken up by the multiple groups attending the 2002 Forum, including “fisherfolk, pastoralists, Indigenous Peoples, environmentalists, women’s organizations, trade unions, and NGOs”. In the years following these forums, the FSM expanded further still, with LVC and the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty (IPC) actively engaging worker, migrant, urban and consumer groups in their work. The food sovereignty movement has thus gradually expanded beyond its initial agrarian base, to include not only a wider variety of food producers, but also groups promoting ethical consumption, fair trade, rural and urban development, and climate action.

As the FSM has grown, definitions of food sovereignty have gradually become more comprehensive and inclusive. The definition of food sovereignty offered in 2007 following the Nyéléni Forum is the most extensive one offered yet, and defines food sovereignty as:

"the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. It puts the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies, rather than the demands of markets and corporations." (see full definition in Table 1)

This definition acknowledges the diverse array of people involved in the FSM and offers food sovereignty not only as a theoretical concept but also as a strategy for change. It focuses on ‘people’ rather than ‘nations’; highlights the importance of environmental issues; and rather than stipulating national production and self-sufficiency, focuses on peoples’ right to determine where and how their food is produced. At the same time, this definition expresses various contradictions (‘the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute and consume food’ arguably includes the heavily criticised actors in the ‘corporate food regime’, for example) and its lack of specificity on various issues has been a source of critique both within and outside of the movement.

Although in practice the FSM often promotes a particular vision of sustainable and equitable food systems (namely peasants and family-farmers producing food appropriate for local consumption using agroecological methods [see our forthcoming explainer What is agroecology?]), the openness of food sovereignty definitions means that this remains an active subject of debate. It is therefore perhaps easier to determine what food sovereignty and the FSM stand against: the Green Revolution and dominance of industrial agricultural practices; neoliberal free trade policies (particularly the export dumping of agricultural surplus into foreign markets); and undemocratic governance of food and agricultural trade (particularly the organisational structure and rules of the WTO). The impact of the food sovereignty movement can be seen in the wider calls to ban, or phase out, the practice of export dumping, and to eliminate export subsidies.

2.3 How does food sovereignty differ from food security?

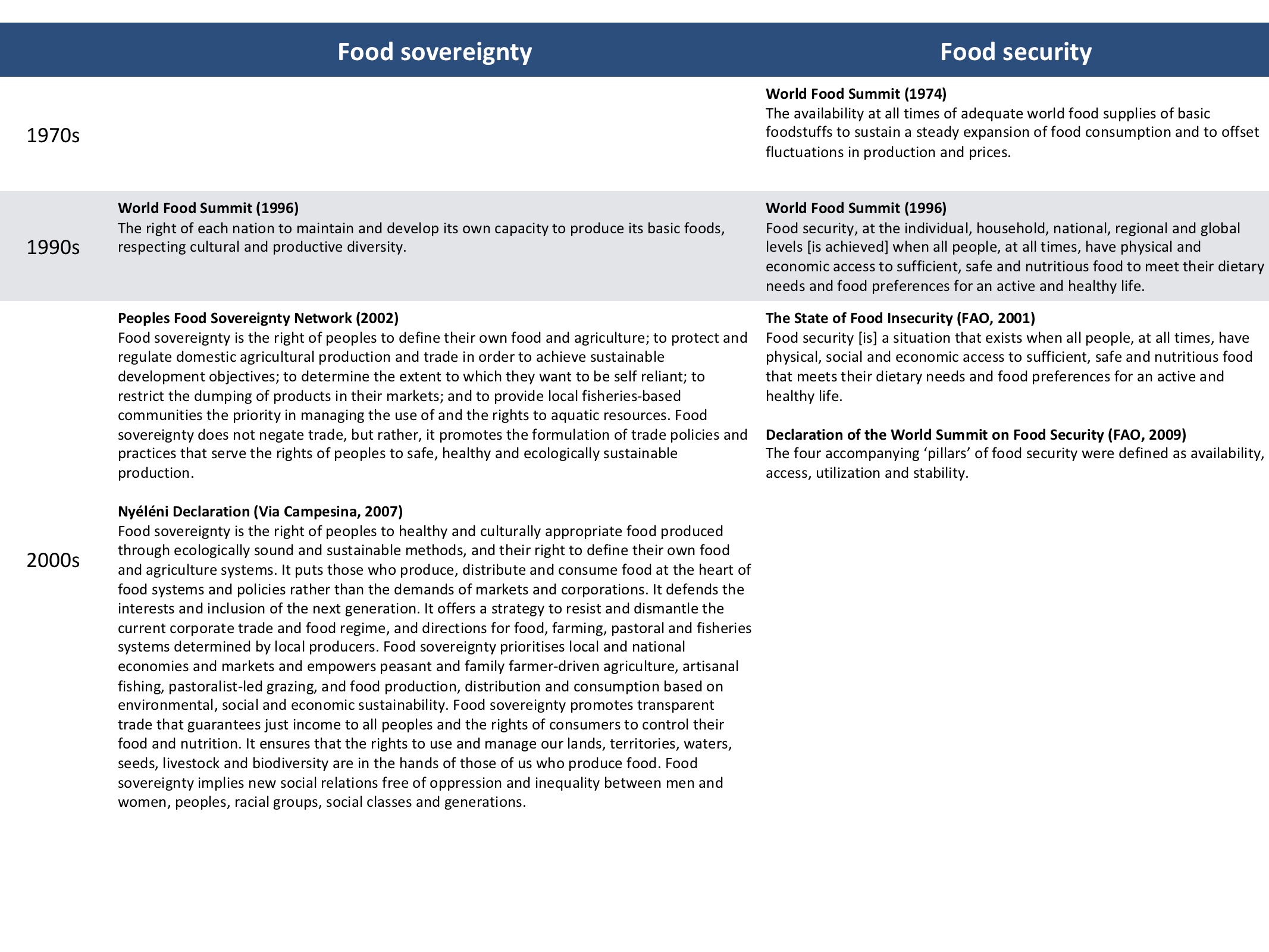

Over time, the FSM has also influenced understandings of food security and the workings of the UN FAO. Food sovereignty is often understood in relation to the concept of food security, as the FSM emerged due to a shared feeling amongst the CSOs and NGOs attending the 1996 and 2002 FAO conferences that food security did not offer an adequate framework for understanding and addressing global hunger and malnutrition. The definition of food security used at the time of these conferences focused on availability of and access to food, and drew attention in particular to the quantity of food in circulation globally (see Table 1 below). Food sovereignty on the other hand highlighted the structural factors underlying global hunger and malnutrition, framing them as political, rather than, technical issues. The FSM drew attention to who was producing food, how and where it was being produced, and the power relations determining these decisions. It rejected understandings of food as a commodity and source of profit, and instead perceived food as, amongst other things, a human right and a source of nutrition and cultural value, inseparable from particular socio-ecological contexts.

Table 1. Evolving food sovereignty and food security definitions,,,,,,

Definitions of food security however have also evolved and changed substantially over time, partially as a result of the activism of the FSM, and the two concepts are now much more closely aligned., Most recent and widely used understandings of food security highlight the importance of ensuring that ‘all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life’. The FAO now acknowledges the wide array of factors influencing food security, such as the economic, social and political mechanisms governing food distribution, and the importance of agency, equity and social, religious and cultural dietary preference (see our explainer What is food security?). The discussion around food security has also become more democratic in recent years with the reconstitution in 2009 of the FAO’s Committee on World Food Security (CFS), which gives representatives from civil society organisations an official platform to influence decision-making on issues related to food security, alongside nation-states, international financial institutions, private sector associations and philanthropic foundations. For many proponents of food sovereignty, the two concepts are not entirely conflicting, and food sovereignty in fact represents part of a strategy to achieve food security., Indeed, the initial LVC definition of food sovereignty explicitly took this stance, stating that the ‘right [to food] can only be realized in a system where food sovereignty is guaranteed… Food sovereignty is a pre-condition to genuine food security’.

Many members of the FSM however see food security and food sovereignty as two conflicting paradigms for understanding food systems. They perceive food security to be deeply embedded in and inseparable from the institutions and processes of the ‘corporate food regime’ and suggest that the concept of food security and its historical focus on production, availability, and efficiency has been responsible for growing corporate influence, environmentally damaging practices, and the marginalisation of smallholder farmers in the global economy., Many in the FSM are therefore keen to distinguish between the two concepts and defend the political agenda associated with the concept of food sovereignty.

The political strategy attached to food sovereignty is perhaps the main feature that distinguishes it from food security. Food security is primarily intended to be a descriptive, rather than normative, concept, and a tool for understanding the complexities of hunger and malnutrition. Food sovereignty, on the other hand, signals allegiance to a particular way of generating change (i.e. movement-based rather than through dominant institutions; democratic and inclusive rather than ‘top-down’; through grassroots political action rather than market mechanisms) and a particular vision of future food systems (i.e. agroecological; democratic; local).

2.4 How does food sovereignty relate to other movements and ideas?

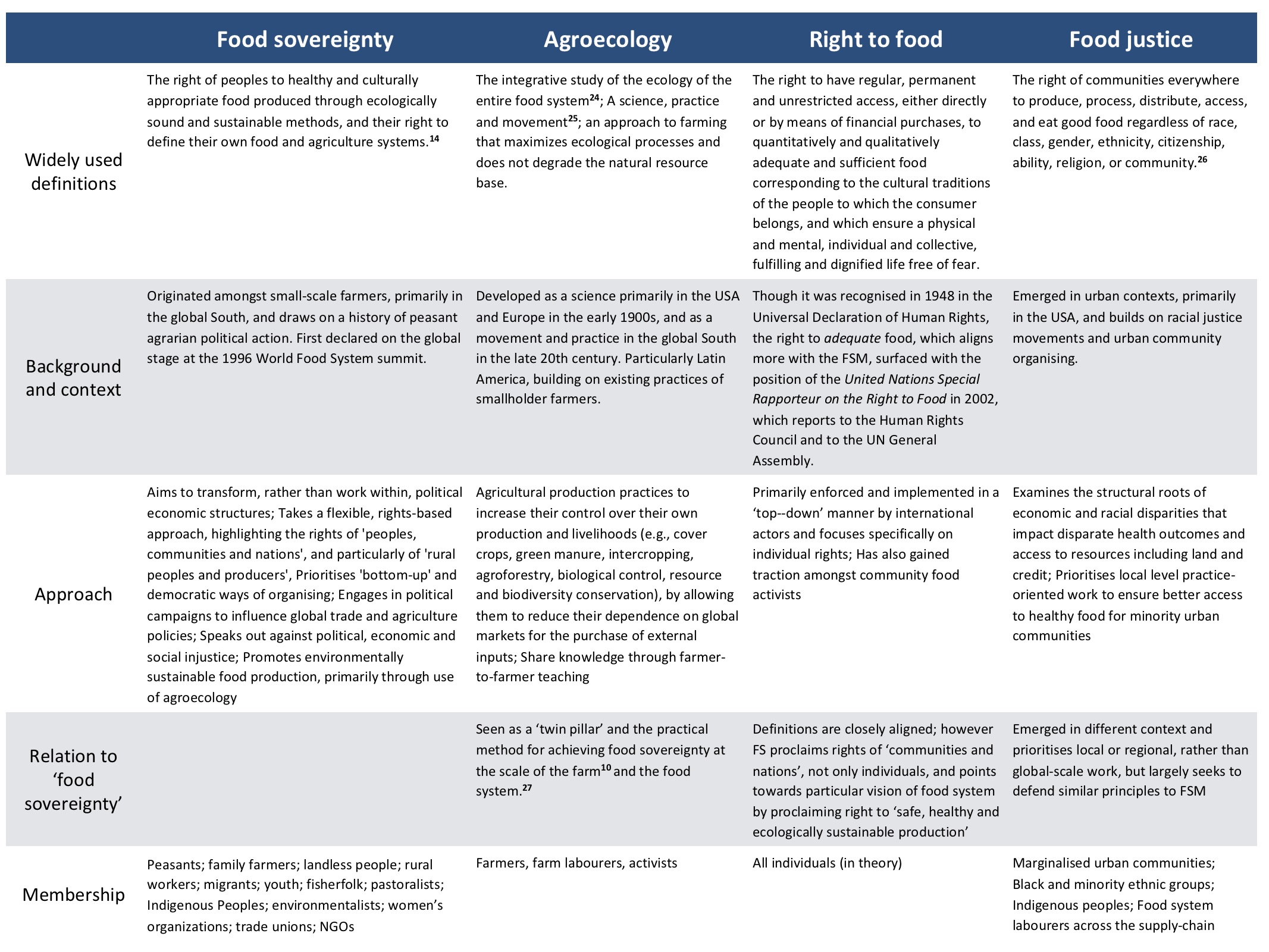

Food sovereignty is closely linked to various other concepts and movements aimed at generating change within the food system, most notably the right to food, the idea of food justice, and the principles and practices of agroecology.

Table 2. Food sovereignty relation to Agroecology, Right to food, and Food justice,,,,,

Civil society organisations and social movements might sometimes opt to work under different banners, promoting either the ‘right to food’, ‘food justice,’ or agroecology. Depending on the context in which they are working, the principles that they seek to defend and the vision of food systems that they promote are often closely aligned. Food sovereignty is distinguished from some other forms of agri-food activism, (for example some forms of organic, fair trade, or community-supported agriculture) in its explicit political focus (aiming to reform global and national governance structures) and its attention to social injustice (aiming to address power imbalances and inequalities both in the food system and in the activities of the FSM itself). Rather than accepting the ‘politics of the possible’, and working within the political and economic structures of neoliberal capitalist societies, the FSM aims to mount a stronger challenge, imagining and enacting new systems of food provisioning and ways of organising society.,

3. Key debates within food sovereignty

Although the FSM does not have a single vision of future food systems that they promote, they widely favour agroecological production and shorter, more local supply chains. This agenda for change, however, has been the source of much debate. Those who favour technological- and market-based approaches to food systems sustainability tend to contest the benefits of agroecology (see our forthcoming explainer What is agroecology?) and criticise the FSM's preference for domestic food production over global free trade. Moreover, both critics and allies of the FSM have suggested that various issues remain underdeveloped in the food sovereignty discourse. The FSM emphasises the rights of food producers; but they do not always acknowledge the diverse views and interests of the peoples that fall within this group, the ways in which the interests of producers might conflict with those of food consumers, or the fact that most producers also rely on purchased foods. It can therefore be unclear how a food system based on food sovereignty would meet the needs of these different people, or indeed, how food sovereignty might be achieved. What role would international trade play, and, likewise, the state? Who would govern a ‘food sovereign’ food system and how would more democratic governance be achieved? Whilst many of these ambiguities are an inevitable result of the inclusive, bottom-up approach adopted by the FSM, they also raise important questions for the future of a food sovereignty agenda, as we explore in the sections below.

3.1. What role would trade play?

Global trade has been the focus of much of the FSM’s political work and the subject of many publications by affiliated academics. The FSM has criticised the prominence of export-oriented trade and the growing power of transnational corporations in the food system, highlighting the ways in which such trends can threaten the livelihoods of small-scale farmers, negatively influence the diets of consumers, and increase the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the food system. The movement has been particularly critical of global free trade agreements and the organisations that regulate them (in particular the WTO), for their lack of transparency or accountability, and for maintaining a trade system that, they argue, promotes the interests of wealthy, industrialised countries and privileges economies of scale over the rights of small-scale producers and sustainable food production.

These criticisms can give the impression that the FSM is anti-trade. While it undoubtedly prioritises local production over global trade and is highly critical of the rules and institutions that allow corporate dominance of global value chains, it is not anti-trade per se. The FSM is however sometimes unclear on what kind of trade should be promoted, the circumstances in which global trade is acceptable, and how a trade system based on food sovereignty might be generated. Some suggest that global trade is acceptable when domestic production cannot meet a country’s needs, and advocate for a more ‘protectionist’ type of trade that would support the interests of small-scale farmers through quotas and subsidies. However, it is not obvious whether ‘needs’ are defined in terms of nutritional requirements only, or also encompass taste and pleasure. Would the trade of coffee and cocoa, for example, be acceptable within a food sovereignty framework? Publications from the FSM also voice support for fair trade initiatives; however, some proponents of food sovereignty are critical of attempts to promote fair trade, suggesting that it is preferable to transform, rather than work within, the structures of capitalist global trade. Disagreement also exists on how changes to trade might be generated and how to establish mutually beneficial relationships between rural and urban areas (see our forthcoming explainer What is agroecology?). While some members of the FSM focus on building autonomous local food systems, freed, where possible, from dependence on global trade, others focus their attention on changing state policy or global trade rules so that small-scale farmers can engage more fairly in national and global markets.

3.2. How would food sovereignty meet the interests of everyone?

It has been suggested by some critics that the FSM’s lack of clarity on trade reflects a failure to acknowledge the diverse interests of its members and the complexities of rural society more widely. Some proponents of food sovereignty, largely non-farmers in the global North, have been criticised for presenting a romanticised and simplified vision of rural life, portraying ‘peasants’ as a homogenous group and failing to recognise that ‘food producers’ include not only subsistence farmers or small-scale family farmers but also commercial farmers, farm labourers, food workers, and landless peasant., Proponents of food sovereignty prioritise inclusivity and democratic decision making through deliberative dialogue processes and convenings to reflect on the evolving needs of regional communities. True representation however is inevitably difficult to achieve in such a large, diverse movement, and some affiliated farmers have reported to researchers that LVC’s actions in the international policy arena, for example, do not reflect farmers’ needs on the ground.

This is perhaps unsurprising, given that different food producers often have very different needs and preferences depending on their economic status, as well as their intersecting racial, ethnic, and gender identities. For example, whilst a food sovereignty agenda might benefit small-scale farmers as a whole, it would not necessarily have positive impacts for women and girls, who are often particularly marginalised in family farming systems., Similarly, whilst some members might benefit from advocacy and actions that develop local markets, others might prefer to increase their presence in global export markets; some might prioritise land reform, whilst others might seek to expand their commercial farms. Moreover, many rural people indicate a desire to move away from agricultural livelihoods entirely and may favour education or training that facilitates employment in urban areas (that said, small-scale farming might become more attractive if its economic viability was ensured through a food sovereignty agenda)., The FSM has undoubtedly become more inclusive over the years: it now explicitly recognises the specific needs of women, ethnic minorities and food system workers and many within the movement are actively attempting to bring together feminist and food sovereignty agendas through participatory quotas., Nonetheless, there can be a tendency amongst some advocates of food sovereignty to present a simplified understanding of rural societies in a way that precludes true representation and that ignores potential contradictions within the movement.

Perhaps an even greater challenge is the goal of meeting the needs of both food producers and consumers. Although the FSM has traditionally focused primarily on the rights of producers, the concept of food sovereignty in fact encompasses all ‘who produce, distribute and consume food’. As LVC themselves point out, [‘F]ood sovereignty was not designed as a concept only for farmers, but for people…’. In economic terms however, the interests of these two constituencies often conflict, as higher incomes for farmers tend to result in higher prices for consumers (although this might be avoided if the profits across the supply-chain and among agro-industry were reduced). There is also a potential tension between the FSM’s commitment to democratically governed food systems (which would allow consumers more control over what they eat and how it is produced) and the promotion of agroecological food production (which arguably demands the consumption of local, seasonal produce, and generally more plant-based diets in historically high consuming countries). Proponents of food sovereignty cite greater control over food production and access to fresh, nutritious food as features of food sovereignty that will benefit consumers. They argue that preference for processed, ‘convenience’ foods is not necessarily an expression of consumer choice, or sovereignty, but rather results from government policies, as well as marketing and lobbying from agro-industry. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that dietary changes might prove unpopular amongst consumers as things stand today, and that normative visions of future food systems might, in some cases, undermine the FSM’s commitments to democratic decision making.

3.3. Who decides? And how?

Some definitions of food sovereignty highlight the importance of the ‘nation’ and domestic food politics, whereas others focus on ‘people’ and their right to shape their food systems. Similarly, within the FSM, some actors prioritise increasing the sovereignty of nation-states by transforming global trade rules and governance processes, and others prioritise increasing the sovereignty of individuals or communities, by generating local or bioregional food systems that provide producers and consumers with more influence and control. Uncertainty about whether sovereignty should reside with the nation-state or the ‘people’ is perhaps inherent to the very concept of sovereignty, and advocates suggest that the FSM asserts a ‘new and modern definition of sovereignty’ that moves between scales., This raises difficult practical questions however about the governance of food systems. Who should determine and govern a locality’s, region’s, or state’s food system and set the goals for the production and distribution of food? And what processes and institutions will help achieve food sovereignty and ensure democratic legitimacy?

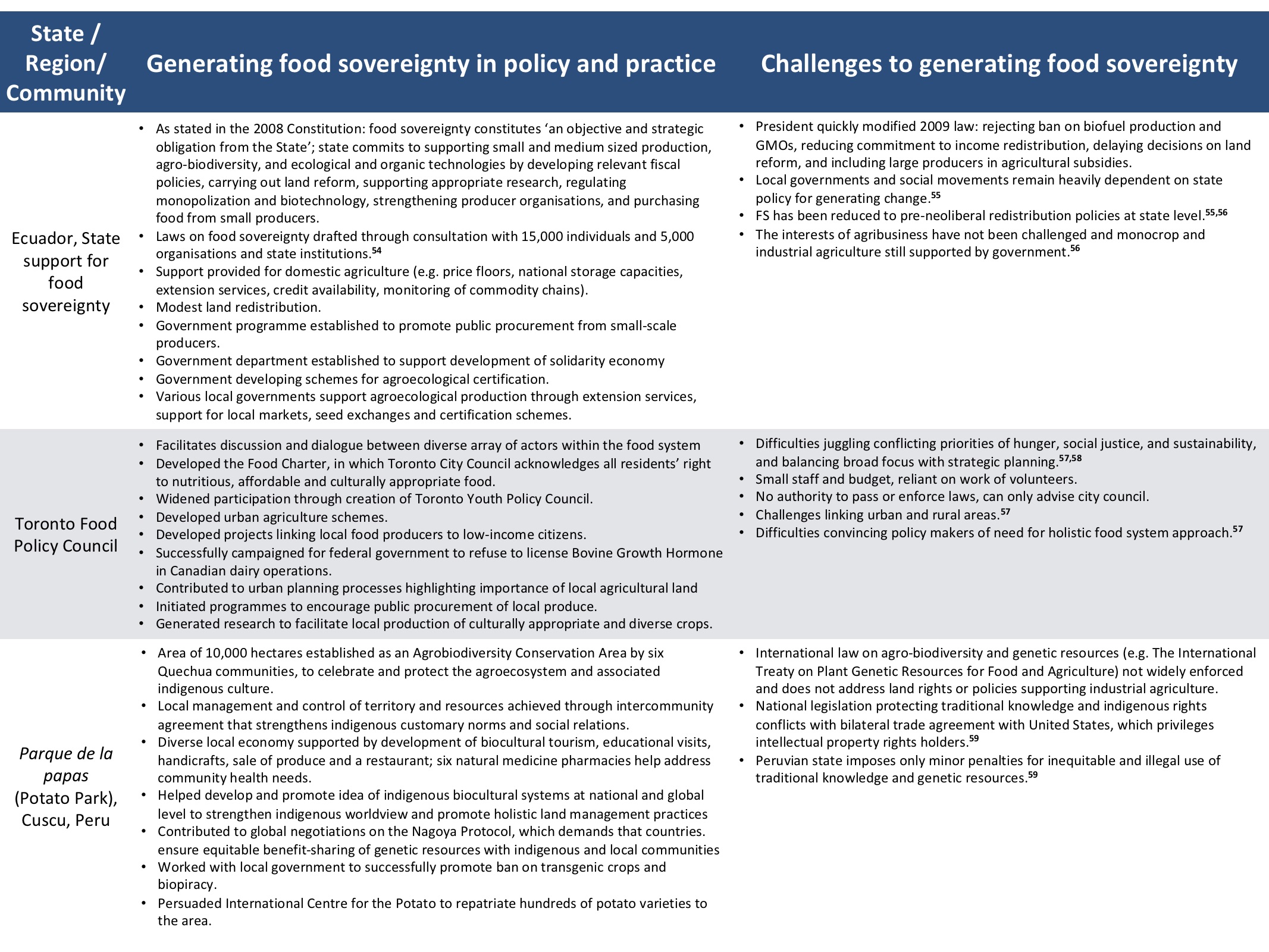

Whether the FSM prioritises the sovereignty of the nation or the sovereignty of the people, it seems likely that the state would need to play an important role in transforming the food system., National governments could help regulate national and global trade, protect and promote agroecological or small-scale farming, ensure that food produced for domestic consumption was distributed fairly on a national scale, and subsidise farmers’ incomes and consumer food prices. As critics both within and outside the movement point out however, there has been little state support for food sovereignty thus far. This might either suggest that few national governments are inclined to challenge the dominant neoliberal political order and offer the necessary levels of state support, or that the food sovereignty discourse does not offer a useful practical framework for public authorities at the national and international level.,

Even in cases where states have formally adopted food sovereignty (for example, Venezuela, Mali, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nepal, and Senegal), the results have been mixed, raising questions about the extent to which, even if inclined to do so, national governments are actually able to transform food systems. Formal recognition of food sovereignty undoubtedly provides social movements and civil society organisations with a new platform, transforming food sovereignty from a strategy of ‘resistance’ (against the state / WTO / dominant food system etc.) into a more positive agenda for change. However, there is less evidence that state support for food sovereignty has actually had significant tangible impacts. In Ecuador for example, the 2008 Constitution framed food sovereignty as an ‘obligation from the State’; a year later however President Correa partially vetoed laws attempting to implement these constitutional changes, with many suggesting that his veto was heavily influenced by agribusiness. This case highlights the difficulty of regaining (food) sovereignty in the context of global free trade agreements and complex corporate consolidation (see Table 3 below). As food sovereignty matures in theory and practice, the FSM faces questions about the scale at which it might best be able to enact change, and the role that the nation-state might be willing, or able, to play.

Table 3. Examples of food sovereignty in policy and practice,,,,,

4. Conclusion

Since it first emerged on the international stage in 1996, the food sovereignty movement has grown to include 200 million members from a diverse array of backgrounds and has helped to shift global conversations on food and agriculture towards greater emphasis on the importance of smallholder farming and on agroecological production, and centring experiences of the food insecure. The FSM has however been criticised for failing to offer a consistent vision of what it stands for or state how food sovereignty might be achieved. Given the bottom-up, inclusive, and democratic approach adopted by the FSM, it is unsurprising, and perhaps even beside the point, that it lacks a coherent vision. Rather than aiming to create a list of issues that it strictly supports or opposes, it prioritises the autonomy of its members, seeking to generate definitions of food sovereignty that reflect its broad base and collectively challenge deep inequalities of power. In practice, the FSM is made up of multiple different constituencies and groups, all working to meet the specific needs of their members and respond to the challenges of their different contexts. It is therefore perhaps more useful to think of food sovereignty as a set of universal principles, namely ‘dignity, individual and community sovereignty, and self-determination’, that bring different actors together ‘to incite context- specific transformation’.

Nonetheless, although food sovereignty has served as an important ‘rallying cry’ for a vast array of actors looking to express their discontent with and transform the dominant food system, both critics and friends of the movement recognise that attention to certain issues would further strengthen its claims. How might food sovereignty help meet the diverse interests of all producers and consumers and bridge class, racial and gender divides? And what would food sovereignty mean for global trade, for governance and for agricultural practices? While there is broad agreement within the movement that ‘business as usual’ is not sustainable, visions for the future coexist and compete with a diverse array of agendas to change the way that we produce and distribute food.

Download the PDF version of this explainer here.

Comments (0)