1. Introduction

Concerns about chronic hunger, malnutrition, climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation have led to increased focus on the world’s food system in recent years, with various actors putting forward different plans to tackle these interconnected issues. In this context, interest in agroecology has grown significantly, and it is now promoted by various social movements, policy makers, civil society organisations and intergovernmental bodies, including the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation. Understandings and uses of agroecology vary however, and there is debate about different definitions of the concept. While some see it as essential for achieving sustainable, equitable and socially just food systems, others offer more fundamental critiques of agroecology as an approach to addressing interconnected food systems concerns. This building block provides an overview of the historical development and various definitions of agroecology and outlines some of the major debates related to its use.

2. What is agroecology? Historical context and definitions

Over the years, the term agroecology has been adopted by a multitude of actors across the world. Different stakeholders emphasise different aspects of the concept, understanding it – as we discuss below – variously as a science, a practice, a movement, or a combination of all three.

2.1 Agroecology as a scientific discipline

The term agroecology began to be used in scientific publications in Europe and the US in the late 1920s, when scientists started to combine principles from ecology and agronomy in an attempt to better understand different agricultural systems. Perceiving the field and the farm as ‘domesticated ecosystems’, scientists focused on the interactions between plants, animals, soils and climate to develop knowledge on, among other things, nutrient cycling, biodiversity and energy efficiency in crop production. The science of agroecology initially focused on the environmental impacts of different productive systems at the scale of the field or the farm, and in certain contexts, for example Germany and parts of Europe, this is predominantly still the case., In other parts of the world however, particularly the Americas, academic understandings of agroecology have broadened to incorporate ‘the ecology of the entire food system’. Many scholars working on the topic now reject purely scientific or technical understandings of agroecology, and instead promote a transdisciplinary, participatory, action-oriented approach combining insights from natural, environmental and social sciences.

2.2 Agroecology as a(n alternative / oppositional) practice

As a practice and as a concept, agroecology has gradually expanded from a set of farming techniques, to a broader, more principles-based approach to agricultural development.

2.2.1 At the farm scale

Many of the farming techniques associated with agroecology have long been used by smallholder farmers around the world, or as part of other systems such as organic or biodynamic. The term agroecology however became popular in the 1970s and 1980s amongst agronomists and farmers seeking to improve and promote alternatives to industrial agriculture, due to their concerns about biodiversity loss, pollution and declining long-term yields. Various agronomists and farmers combined knowledge from traditional and indigenous farming systems and agroecological science to develop a set of farming techniques that would optimise production while minimising external inputs and avoiding the degradation of natural resources (see Box 1 for more detail of the on-farm practices associated with agroecology). Agroecology became particularly popular in the global South, especially in Central and Latin America, amongst small-holder farmers seeking to improve their established farming systems at little extra cost, and to confront challenges such as soil erosion and climate disruption.,

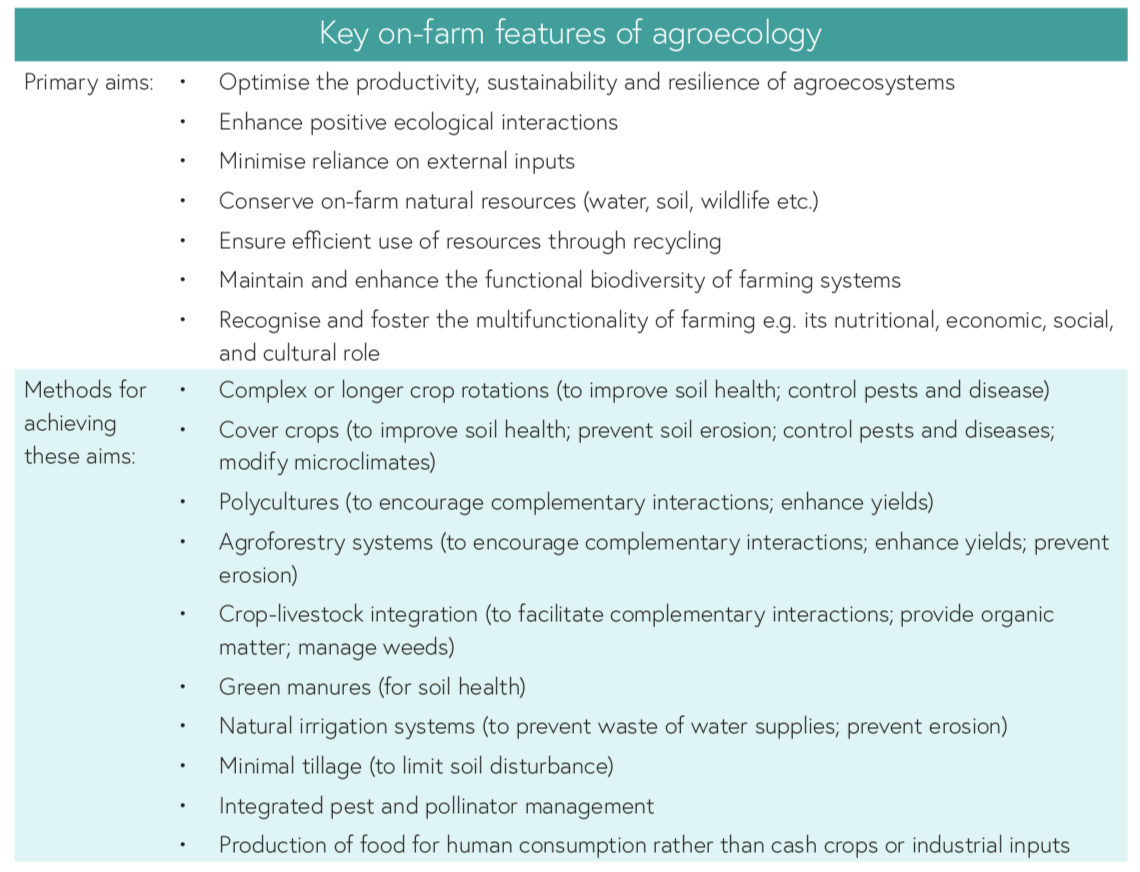

Box 1. Key on-farm features of agroecology

2.2.2 Moving from practices to principles

The practice of agroecology quickly expanded beyond a narrow attention to farm practices, in response to political and economic change. In many cases, rural poverty and inequality increased dramatically following the Green Revolution, with large numbers of farmers unable to afford the ongoing costs of agricultural inputs. These problems worsened as food systems became increasingly globalised, and many smallholders struggled to compete with large-scale capital-intensive agriculture in markets flooded with subsidised products from industrialised countries. In this context, the adoption of agroecology was often motivated by economic, as well as ecological, concerns: farmers sought to minimize inputs in order to reduce costs, and to diversify crop production in order to improve household food security and nutrition. Farmers worked alongside agrarian movements and civil society organisations (CSOs) to further improve the economic viability of smallholder farming, developing local markets and producer co-operatives to add value to produce and avoid prices set by large-scale processors and retailers in global markets.

Agroecology also became associated with specific educational and organisational practices. Agroecological techniques were developed through collaboration between agronomists and farmers and on-farm experimentation, and smallholders shared knowledge through field schools and farmer-to-farmer learning. These democratic methods of knowledge exchange further distinguished agroecology from the Green Revolution, which was developed and implemented primarily in a top-down manner by national governments and large research institutes, with little input from farmers. Indigenous farming systems informed many agroecological practices and agroecology often became associated with wider efforts to defend and revive indigenous cultures - for example local food varieties, seed saving practices and spiritual beliefs about “Mother Earth” (see Box 2 for more information on the link between agroecology and traditional farming systems).

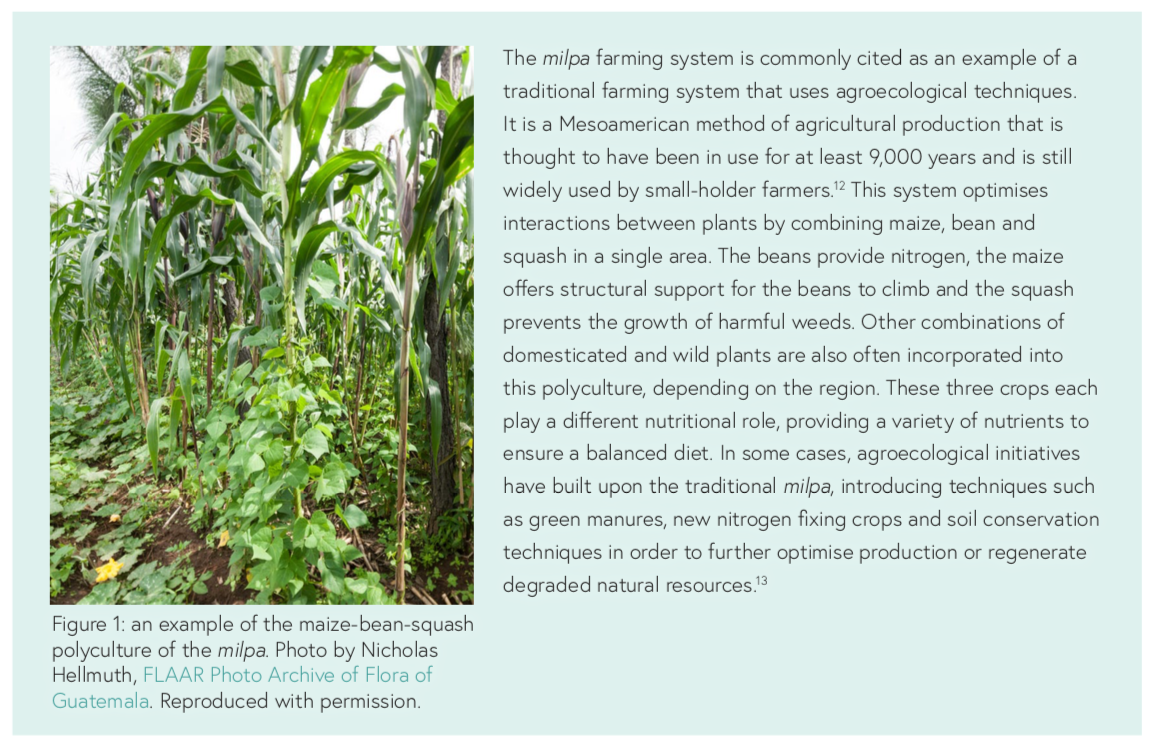

Box 2. Agroecology and traditional farming systems: the milpa,

The practice of agroecology thus developed in response, and as an alternative, to a particular political economic context, and specific set of social and power relations. Over time, it expanded its focus and evolved into a broader, more principles-based approach, prioritising democratic methods of governance and knowledge exchange, economic diversification and solidarity relations, and respect for diverse cultures and traditions. As can be seen in the FAO’s definition of agroecology (see Box 3), such principles are important to current understandings of agroecology, including those promoted by more mainstream actors.

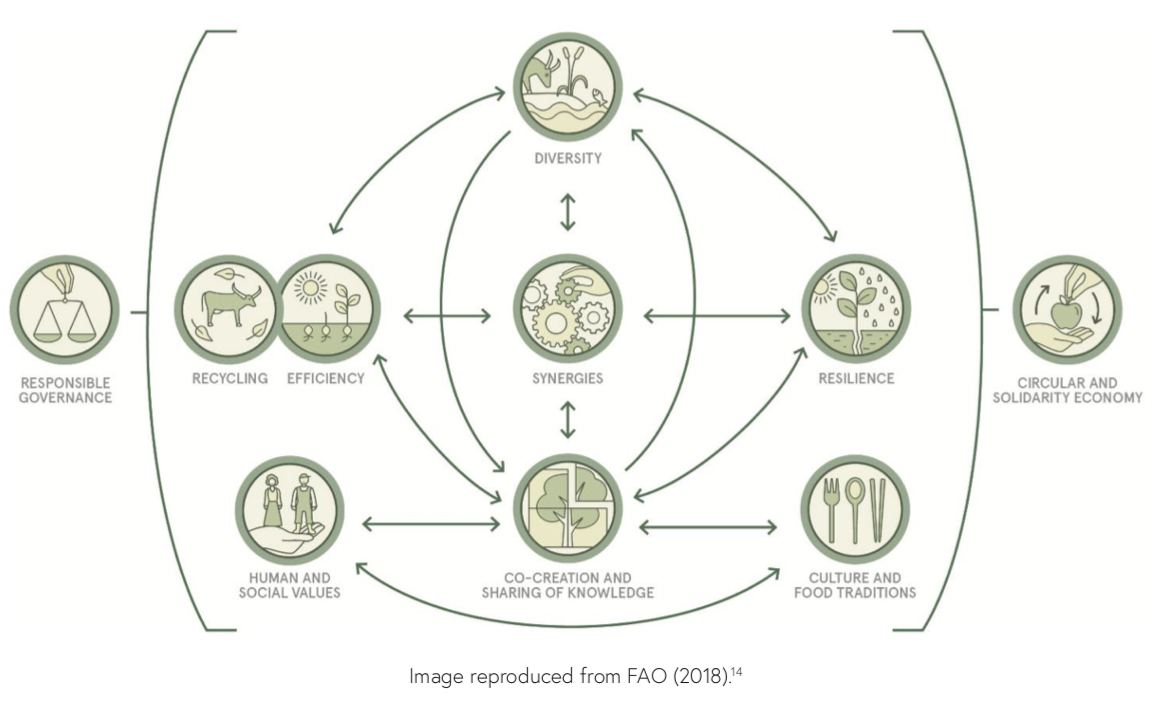

Box 3. FAO 10 elements of agroecology

2.3 Agroecology as a movement

During the 1980s and 1990s, many of the farmer organisations, academics and NGOS promoting agroecology united in their rejection of structural adjustment policies and neoliberalism and began to combine agroecology with political campaigning on trade and agriculture policies at a national and global scale. Agroecology thus became associated with wider collective efforts for change, and a form of ‘politically engaged agroecology’ or ‘agroecology as a movement’ emerged.

This is particularly evident in the way that La Vía Campesina (LVC), a transnational peasant movement, promotes agroecology. LVC describes agroecology as ‘a key form of resistance to an economic system that puts profit before life’ and perceives it as the means for achieving food sovereignty (see our explainer What is food sovereignty?). This association of agroecology with food sovereignty unites different initiatives and actors (from small-scale farmers in the global South to academics in the global North) behind a vision of democratic, equitable and just food systems based on agroecological small-farm production., For many activists promoting it as a movement, agroecology is inseparable from a particular set of values and priorities, including the expansion of collective rights and the commons; racial and gender equality; respect for diversity; and the rejection of anthropocentric worldviews and solely technological- or market- based responses to problems.

Agroecology’s broad definition, as a science, practice and movement, reflects the different interests and needs of the multiple farmers, agronomists, scientists, social movements and CSOs who have contributed to its development. Interest in agroecology can therefore be motivated by a wide variety of concerns, including a desire to transform the global food system and address global injustices; to re-valorise and share traditional and indigenous knowledge; to ensure the economic viability of smallholder farming; to improve household nutrition; to address concerns about the environmental effects of industrial agriculture; to help conserve on-farm natural resources; or to study and optimise interactions occurring within agroecosystems.

3. Contentious issues

Due to its conceptual breadth, there has been much debate among the various actors involved about what agroecology is, or ought to be, and its relation to other ideas for food systems change. Agroecology also receives criticism from sceptics outside the movement, who question agroecology’s potential to produce enough food for a growing population and who challenge some of the assumptions underlying claims that agroecology will generate more socially just food systems. The following subsections explore some of these debates and contestations.

3.1 Contentious issues: who defines agroecology? And how far reaching is it?

Many people draw attention to the ways in which approaches to agroecology shift according to the values and priorities of different actors. As agroecology gains a wider following, questions therefore increasingly emerge about possible tensions that might arise in agroecology’s application and the ways in which it interacts with other practices and scales as it evolves. To what extent, for example, must farmers adhere to the multiple elements of agroecology in order to describe their farm as agroecological? Can farmers producing for commercial export markets, subcontracted by large-scale retail or processing corporations, or renting land from large financial institutions be classified as agroecologists, if they use on-farm agroecological practices? And what of farmers who promote local food systems and methods of exchange, but utilise chemical inputs in certain circumstances?

Social movements and affiliated academics often distinguish between the ‘reformist’ or pragmatic approach of more mainstream organisations, and ‘radical’ or transformative understandings of agroecology that focus on agency, democracy, equity, and political and economic transformation. They are often particularly critical of actors that approach agroecology merely as a technical tool or set of agronomic techniques. They vehemently reject, for example, the increasing use of the term by large corporations, whom they accuse of choosing particular elements of agroecology to mitigate the food system’s worst environmental and social impacts, so as to continue ‘business as usual’.,

Many agroecologists also oppose suggestions that agroecology could contribute to sustainable intensification (SI) (see our explainer What is sustainable intensification?) or climate-smart agriculture (CSA) if combined with other practices, including chemical inputs and genetically modified crops. This use of agroecology is increasingly popular, particularly in Europe and the UK,, and some people suggest that supporting only transformative, principles-based approaches to agroecology might limit the adoption of agroecological practices. However, social movements and affiliated activist-academics claim that it is essential to defend such understandings of agroecology if it is to maintain its transformative potential. They denounce SI and CSA for failing to explicitly address the socio-economic and power inequalities of the food system, and suggest that the use of expensive technologies will maintain corporate control of agri-food systems and extractive, environmentally-harmful approaches to nature.

The on-farm practices of agroecology and organic farming are often very similar. Many people therefore perceive organic as a ‘legally defined and proven agroecological approach’, that regulates agroecological practices by using legal standards and certification to enforce the removal of chemical inputs. As with agroecology however, many people distinguish between different approaches to organic. They suggest that broad versions of organic (which aim to achieve low-input farming through the recycling of resources within the farming system, and transform socio-economic structures and relationships with nature) share many similarities with agroecology. However, they also highlight that in some cases, particularly in the US, organic has been reduced to a much narrower understanding, that allows farms to simply substitute chemical pesticides and fertilisers for non-chemical inputs, in order to meet certification standards and achieve market premiums. Agroecologists are keen to distinguish agroecology from these narrower forms of organic, suggesting that they maintain monocultures and large-scale land ownership and fail to truly transform agricultural practices. Debates within the organic movement thus mirror discussions about different definitions of agroecology, with concern that both concepts might be co-opted by agri-business in response to growing market opportunities.

3.2 Contentious issues: can agroecology feed the world?

With agroecology increasingly cited as a tool for reducing or eliminating global hunger and malnutrition, agroecology’s ability to feed a growing global population has become a source of much debate. As we discuss below, people engage with the question of ‘feeding the world’ in different ways: while sceptics focus on productivity and agroecology’s ability to ‘scale up’, proponents of agroecology emphasise resilience, equity and nutrient security, and agroecology’s role in achieving these goals.

3.2.1 Is agroecology less productive?

There is little research on yields from farming initiatives explicitly defined as ‘agroecology’, and findings have been heavily contested. Studies of productivity in organic farming are relevant, however, due to the similar practices used. Research has often suggested that industrial agriculture produces approximately 20% higher yields than organic farming for a given area of land used., The productivity of different farming systems is nevertheless highly contextual and depends greatly on the region, timeframe, crop type, methods, and measurement processes in question. Some people suggest that studies tend to over-estimate the productivity of organic agriculture, as they often fail to account for the land or cropping seasons needed to produce green manure, that might otherwise have been devoted to food production. A variety of other studies however are more optimistic about organic farming’s productivity: they find the yield gap to be less significant for certain crops (e.g. fruit and oilseeds); when ‘best’ organic practices are used (i.e. agroecological techniques such as crop rotation and multi-cropping); and when total outputs, rather than the yield of specific crops, are compared.,, They also highlight organic agriculture’s ability to maintain yields consistently over longer time periods and in the face of environmental stresses, particularly drought. Much research highlights the potential for organic farming techniques to dramatically increase agricultural productivity as compared with baseline yields in countries with large numbers of marginalised smallholder farmers. These studies suggest that agroecological methods are generally low-cost, easily accessible and familiar to farmers already employing similar techniques;,, however, some scientists contest the possibility of improving soil fertility through organic methods in heavily depleted soils, for example in Sub-Saharan Africa. Many people emphasise that organic yields would increase further if organic farming were to receive the same level of research, investment and subsidies that conventional farming has to date.

3.2.2 Moving beyond productivity – what is enough?

In response to debates about productivity however, agroecologists highlight the need to move beyond a narrow focus on yield to look at the diverse benefits of agroecology and the wider changes needed in the food system. They emphasise for example the importance of food’s nutritional quality, the social and environmental conditions associated with its production and distribution, the ability of different farming systems to endure environmental and climate disruption, and the role that farming must play in generating fair and sustainable livelihoods (i.e. providing income to cover services such as health care and education and/or ensuring access to necessary natural resources such as firewood and medicinal plants). Proponents of agroecology also point out that hunger and malnutrition, at least at the global level, do not result from a lack of available food but from inequitable and unsustainable patterns of distribution and consumption. They therefore emphasise the importance of political and economic change, as well as changes to production., Indeed, comparisons of industrial and agroecological food systems that account for changes in diet (particularly the reduction of grain-fed livestock, i.e., pigs and poultry), food waste, and industrial crop usage, find that agroecological farming can produce enough food for a growing population, and can do so in a sustainable and equitable manner.,

3.2.3 Can agroecology ‘scale up’?

It is widely recognised that, if agroecology is to play a significant role in the food system, it will need to ‘scale up and out’ (i.e. be applied on a larger scale, such as on larger farms, and/or over a wider area, on more small-scale farms). Agroecologists emphasise how farmer-to-farmer networks, NGOs and agrarian movements have dramatically increased the uptake of agroecological practices, particularly amongst smallholders in the global South., Many actors continue to build on this tradition and adopt a ‘bottom-up’ approach to scale out agroecology.

It is less clear however how agroecological practices might be used on large farms reliant on agricultural machinery and a small workforce, given that diversified production tends to require a high input of labour and is not easily supported by machinery designed for standardised cropping systems. This suggests that while agroecology could easily be ‘scaled out’ in areas with large numbers of small farms (or with a large rural population ready to farm following land redistribution) or perhaps be ‘scaled up’ in areas with a rural workforce able to provide labour on large agroecological farms, it might be less appropriate in areas with smaller rural populations or, as is discussed below, if people object to labour intensive work. Critics draw attention to increasing rural-urban migration to question the viability of agroecology. However, agroecologists challenge assumptions about the inevitability of continual urbanisation, and suggest that agroecology can provide rural livelihoods and therefore stem or reverse migration from rural areas.

Sceptics also highlight the difficulties of ‘scaling out’ agroecology, given the potential complexity and inefficiency of distributing produce from multiple small farms on a wide scale in urban areas. In response to such critiques, agroecologists reflect on the food systems that might be developed if agroecology were to receive the high levels of state and private sector resources mobilised during the Green Revolution. They point to cases such as Cuba and India,, where government support for agroecological food systems has increased the uptake of agroecology, and facilitated the emergence of local markets for the sale of domestically produced staple crops (although there is debate about the extent to which these have improved access to affordable food amongst urban populations)., Agroecologists also highlight the successes of social movements and CSOs in creating territorial rural-urban food networks, and developing plans for circular city-region food systems that facilitate food distribution in urban areas and the use of urban waste on farms.,

3.3 Contentious issues: can agroecology generate a more equitable food system?

Proponents of agroecology, particularly transformative agroecology, present a vision of equitable, inclusive food systems, based on the principles of food sovereignty - ‘dignity, individual and community sovereignty, and self-determination’. They highlight the role that agroecology can play in achieving these ideals, by addressing socio-economic inequalities and power imbalances in a food system dominated by large-scale agri-business.

Agroecologists emphasise the economic advantages of agroecology for smallholder farmers and the role that agroecology can therefore play in addressing corporate control of agri-food value chains. Initial studies suggest that agroecology improves farmer incomes and generates rural livelihoods and economies, allowing smallholder farmers to remain in rural areas and maintain agricultural ways of life.,, Agroecologists also highlight how agroecology’s democratic and inclusive methods of knowledge exchange and social organising facilitate the inclusion of indigenous communities and minority groups. They emphasise the importance of such processes for people whose practices and values have often been marginalised by mainstream agriculture and development programmes imposed by policy makers or development practitioners.

There are undoubtedly, however, many complexities and challenges involved in generating social movements and food systems that benefit multiple different people and communities. There has sometimes been a tendency for the agroecology and food sovereignty movements to overlook such complexities, and present a simplified and idealised understanding of peasants and family farmers. Many within the movement however increasingly acknowledge the diverse, and potentially conflicting, interests of different types of food producers (e.g. landless people working for wages, peasants producing for local markets, or middle-sized family farmers producing for global export) as well as the various gender, racial and ethnic inequalities that permeate rural societies., Addressing these complexities remains a challenge for the agroecology and food sovereignty movements. Efforts are, however, being made to ensure that the benefits of agroecology are widely shared, by broadening the movement’s membership base and promoting land reform and gender equality as core components of agroecology.

Some critics however are less convinced of the benefits of agroecology, and question whether this approach really is desirable or beneficial for smallholders. They draw attention in particular to the high labour input associated with agroecological farming and suggest that agroecology ties people to poverty-stricken and labour-intensive rural livelihoods. They suggest that this is particularly problematic for women, who often undertake additional farm work., These critics promote alternative visions of rural development instead, suggesting that non-agrarian livelihoods might be preferable for smallholders, or that smallholders lives will be best improved by agricultural modernisation, improved technological inputs and better access to global markets.,

Some people also express concerns about the impact that agroecological food systems would have on consumers, particularly marginalised, less affluent communities. Agroecological food could be more expensive, as fair returns for farmers often result in higher prices for consumers. Moreover, dietary changes associated with agroecology (e.g. reduced meat, sugar and processed food consumption), might disadvantage some people more than others, as reliance on processed food often stems from a lack of financial (and other) resources, and many people in less wealthy countries are only beginning to incorporate meat into their diets as incomes increase. Agroecologists however suggest that the wider socio-economic and political changes associated with agroecology would help confront many of these issues. Government support for agroecology, for example, would reduce profits for agro-industry and marketing of processed foods, and therefore help avoid major food price rises while also reducing dependence on or preference for processed foods., People also suggest that global disparities in meat consumption can be addressed through reduction in historically high consuming nations, thus allowing for increases in meat consumption elsewhere.

3.4 Contentious issues: environmental sustainability and the question of working with nature

Advocates of agroecology suggest that farming practices that avoid chemical inputs, foster on-farm biodiversity and ‘work with’ nature are better for the environment than industrial agricultural practices. However, some critics challenge these assumptions.

3.4.1 What are the environmental impacts of agroecology?

Agroecologists argue that there are multiple and connected environmental benefits to agroecology, particularly compared with industrial farming methods. They emphasise the role that agroecology can play in tackling soil erosion and degradation; avoiding pollution associated with the use of pesticides and fertilisers; sequestering carbon; and reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reliance on fossil-fuel inputs (through a reduction in on-farm machinery, long-distance food transportation, and energy-intensive off-farm processes e.g. the production of ammonia)., Although it is very difficult to measure the impact of different agricultural practices on atmospheric carbon, various studies highlight the role that agroecological practices such as agroforestry, cover crops and the inclusion of native vegetation and perennial crops, can play in sequestering carbon and reducing emissions.

Some people worry however about the indirect impact that agroecology could have on biodiversity, particularly on specialist species, whose numbers tend to decrease in agricultural landscapes. In what is often framed as a choice between ‘land sparing’ and ‘land sharing’ critics express concerns that agroecology, and other low-input types of agriculture, would use more land than necessary for agri-food production, particularly once the production of green manure is considered (see our explainer on What is the land sparing-sharing continuum?). They suggest that higher net levels of biodiversity would be achieved by employing higher yielding practices, which could, in theory, release more land for dedicated conservation and carbon sequestration efforts elsewhere, for example through afforestation or rewilding (see our forthcoming explainer on rewilding).

Many people, however, criticise the limited focus on biodiversity and yields in ‘land sparing’ / ‘land sharing’ debates, and the emphasis placed on the intrinsic value of conserving wild species. Such commentators highlight the importance of other natural resources provided by sustainably managed agroecosystems, such as clean water, soil health and carbon sequestering landscapes. In particular, agroecologists emphasise the importance of agricultural biodiversity, highlighting the role that diverse agroecosystems play in increasing resilience to climatic stresses and pests and diseases, and in ensuring that farming systems can be adapted to local ecological niches. Moreover, many people challenge assumptions that agroecology would require the conversion of more land for farming, suggesting that truly agroecological systems (based on changes to diet, food waste, use of crops for feed and fuel and perhaps wider political economic changes) would allow for both agricultural biodiversity and land spared for nature.,,

3.4.2 (How and why) should we work with nature?

The desire to work with nature and build upon ecological processes is fundamental to agroecology (and also to related agricultural practices such as organic and regenerative agriculture). Rather than centring the design of agroecosystems on human (or market) demand, agroecologists draw on a detailed understanding of the ecosystems and natural resources of different contexts, aiming to promote and modulate interactions taking place within natural communities to deliver a range of functions and services.

Some critics however contest the value of working with or mimicking nature, questioning in particular the ecological thinking upon which agroecology is founded. Drawing on Darwinian evolutionary biology to suggest that natural selection happens only at the level of individual species, not ecosystems more widely, they undermine conceptions of ecosystems as ‘superorganisms’ and question whether natural communities have the capacity to organise themselves to reach a state of equilibrium or improve over time. Concluding that ‘evolution has improved trees much more consistently than it has improved forests’ they suggest that attempts to build on the interactions of ecosystems are misguided, and that the study (and improvement) of individual plants and animals would be more worthwhile.,

This Darwinian focus on individual components of the natural world, however, is the subject of growing critique. Increasing numbers of scientists and social theorists focus instead on mutualistic and symbiotic relationships within natural communities, highlighting examples such as pollination and fungi-plant relationships to demonstrate how certain components of ecosystems construct ecological niches and provide essential services that allow other organisms to flourish. Such scientists suggest that although ecosystems are fluid and contingent and might not have as powerful an optimisation mechanism acting upon them as natural selection, they also undoubtedly possess features that promote their ability to reproduce, adapt and sustain themselves over time. This resilience is particularly valued by agroecologists. They emphasise that while ecosystems might not maximise productivity, they sustain themselves in the face of serious disruption, and in this sense, provide a useful model for agriculture. This kind of thinking provides the foundation for the increasing interest in soil biodiversity and symbiotic relationships within soil ecosystems, which increasingly informs work on agroecology, regenerative and organic farming and has been taken up by global bodies such as the UN FAO.

Although there is debate in the scientific community about how ecosystems organise themselves and evolve, it seems that disagreements about the value of working with nature often arise due to different priorities for agricultural systems. While sceptics primarily value productivity and efficiency, agroecologists highlight the importance of resilience and long-term stability. They therefore disagree on which features of the natural world farmers should choose to encourage and build upon, and on the extent to which examples derived from the study of ecosystems might be usefully applied in agriculture.,,

4. What future for agroecology?

In the context of concerns about our current climate crisis and increasing corporate consolidation in agri-food value chains, increasing numbers of stakeholders are arguing for agroecology as a way of providing healthy nutritious food in an equitable and sustainable manner. Certain aspects of agroecology now feature in food policy dialogue, particularly in Europe and the EU, and elements of agroecology, for example farmer learning practices, are being used to encourage transitions towards more sustainable, resilient farming systems. However, as both critics and proponents of agroecology point out, there are still questions about the ways in which agroecology could and should relate to technological change, global trade and corporate agriculture. There is also uncertainty about the viability of agroecology on a larger scale given its dependence on changes to political and economic processes, consumption habits and rural-urban dynamics.

In their efforts to generate significant food system transformation, agroecologists sometimes avoid these complex questions and reject all but the most far-reaching and radical understandings of agroecology. While such definitions of agroecology might be useful as a political tool, they can also make agroecology vulnerable to criticism from sceptics who perceive it as a dogmatic movement that restricts smallholder farmers, based on an ideological opposition to technology, modernisation and capitalism. This said, these more simplified, oppositional understandings of agroecology do not necessarily reflect the complexities of its use on the ground. As many agroecologists increasingly recognise, transitions ‘are often messy, chaotic and non-linear’ and are highly context-specific., It therefore remains to be seen how agroecology will be shaped by the increasingly diverse array of actors involved; the extent to which it will overlap with, or be surpassed and superseded by, other plans for food systems change; and what kinds of sustainable food futures it will foster.

Download a PDF version of this explainer here.

Comments (0)