1. Introduction

Ecomodernism is an environmental philosophy rooted in the belief that technological progress can allow humans to flourish while minimising our impacts on the environment. Ecomodernists define human flourishing as both “democracy, tolerance, and pluralism” and material wellbeing in the form of access to “modern living standards” for all. According to ecomodernist philosophy, an essential approach to achieving both prosperity and protecting nature is to free up land for conservation by intensifying the production of food and other resources using technology. Governments, the private sector, and civil society should work together to achieve this goal.

Ecomodernism as a movement encompasses a diversity of views. However, here we focus on the well-known Ecomodernist Manifesto of 2015, which is perhaps the most coherent exposition of the ecomodernist philosophy. This form of ecomodernism is most visible in the United States but is also influential in other countries, including the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

We first describe the values, goals, and practical solutions promoted by the Manifesto and what they would mean for land use and the food system. We then explore the history of the ideas that underlie ecomodernism, including academic concepts from social science, and their relation to different forms of environmentalism. Finally, we discuss the main critiques of the values and evidence underpinning ecomodernism.

Box: A note on scope, sources and the review processThe aim of this piece was to produce an overview of what ecomodernism is and what the main contestations are around the concept from both proponents and critics of the idea. It is beyond the scope of this piece to conduct a detailed assessment of the scientific validity of the many claims made by different stakeholders. More salient, for this piece, are the arguments that people construct about the concepts. We have therefore cited a number of sources in addition to academic journal articles, including reports and blog posts, because this is where people are talking specifically about ecomodernism. Through TABLE’s peer review process, we had hoped to produce a description of the disagreements that “both sides” can agree accurately reflects the state of the debate. We have failed to do this. Some reviewers felt that the piece was strongly biased against ecomodernism, while other felt it was strongly biased in favour of it. Some felt that some of the criticisms and counterarguments to be scientifically invalid or “strawman” arguments and that they should not even be included in the piece lest, by describing them, we lend them validity. Our general approach has been to keep these descriptions of the arguments in the piece, because regardless of their validity or otherwise, they represent strong influences in the live and contentious debate around ecomodernism. Although the review process has not resulted in agreement among the reviewers, it has however been extremely helpful in bringing several points of fundamental disagreement to the surface – these will be discussed further below. Note that one reviewer felt unable to endorse the final piece and wishes to remain anonymous. We would like to stress that (a) we are very grateful to all our reviewers for their comments and suggestions, which have strengthened the piece, and (b) their being named as a reviewer does not imply that they agree with everything in this piece. |

2. Ecomodernism according to the Manifesto

The term ecomodernism has been used at least as far back as 1993, but has gained prominence since the 2015 publication of the Ecomodernist Manifesto by a group of 19 “scholars, scientists, campaigners, and citizens”. The authors include Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger, co-founders of The Breakthrough Institute, a Californian think tank that advocates for technological solutions to environmental challenges.

The Manifesto summarises ecomodernism:

“In this, we affirm one long-standing environmental ideal, that humanity must shrink its impacts on the environment to make more room for nature, while we reject another, that human societies must harmoni[s]e with nature to avoid economic and ecological collapse.”

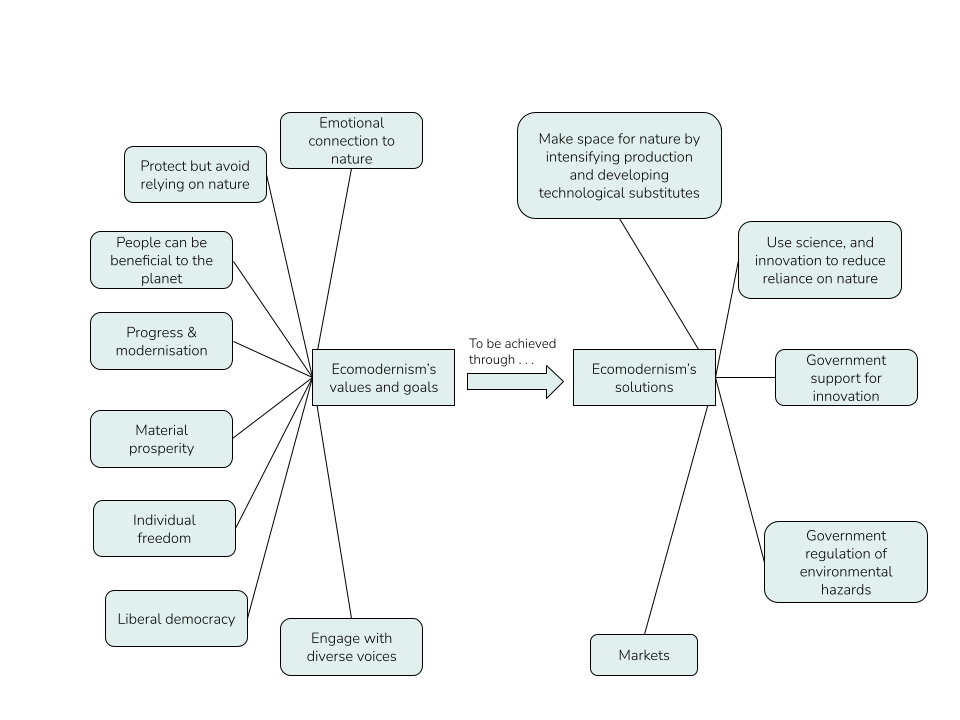

Figure 1 gives a simplified overview of ecomodernism’s values, goals, and solutions. The next two sections expand on each of these as described by the Manifesto; critiques of ecomodernism will be discussed in later sections.

Figure 1: An overview of ecomodernism’s values and goals as well as its proposed solutions for meeting these goals. Graphic produced by TABLE.

2.1 Ecomodernism’s values and goals

Ecomodernism in the form described by the Manifesto places high importance on ending material poverty through economic and social development, and giving all people access to “modern living standards”. It claims that people currently living in poverty rightly prioritise improving their quality of life over tackling environmental challenges.

It also prioritises progress and modernisation, understanding them to mean “vastly improved material well-being, public health, resource productivity, economic integration, shared infrastructure, and personal freedom”.

Freedom for all individuals is important. The Manifesto refers to “liberating” people from hard agricultural labour so that they can pursue other endeavours (including arts and culture) and calls for women to be freed from “traditional gender roles” and to have control over their fertility.

People can have a good relationship with the planet; modern human society is not necessarily harmful. The Manifesto states that “knowledge and technology, applied with wisdom, might allow for a good, or even great, Anthropocene.”

This relationship with nature is two-fold. Humans should generally reduce their demands for natural resources, including land use for agriculture and settlements, by increasing land use efficiency and settlement density as opposed to living rural lifestyles. At the same time, there is value in having emotional or spiritual connections to both wild and cultural landscapes,.

Society should be based on the principles of democratic governance, tolerance, and pluralism – both for their own sake, and as essential tools to navigate environmental challenges. Although the Manifesto proposes specific technological solutions (see the next section), it recognises that they will not suit all social, economic, cultural, and political contexts. To avoid imposing top-down solutions, it is therefore important to engage with diverse voices.

2.2 Ecomodernism’s proposed solutions

To reach ecomodernism’s goals, the Manifesto sets out a general approach of making space for nature by intensifying production – that is, for yields per unit of resource use (including land and labour) to be increased – as well as by developing substitute technologies, such as nuclear energy in place of wood for fuel. Science and innovation should therefore be used with the aim of reducing human reliance on goods and services from ecosystems.

Ecomodernists therefore reject societal dependence on forms of production that they see as inefficient in their use of either land or labour. For example, the Manifesto raises concerns about the large area of land used by climate solutions such as biofuels, and argues that pre-industrial societies had greater environmental impacts per capita than we have today – hence their subsistence strategies are not suited to sustaining today’s much larger populations. It also sees labour-intensive agriculture as an impediment to modernisation (specifically urbanisation), and labour-efficient agriculture as freeing people to pursue other endeavours.

The Manifesto argues that “[t]echnological progress is not inevitable” if left to the market alone. Although it does not support central planning of the economy by the state and believes that markets have an important role to play, governments should actively support innovation by collaborating with businesses and civil society, as well as regulate environmental hazards.

3. An ecomodernist food system

Ecomodernism applies to the whole economy, but is particularly relevant to food because farming occupies so much of the Earth’s surface: one third of ice-free land is permanent grazing or cropland, with more being intermittently used for seasonal grazing.

Ecomodernists advocate for agriculture to be intensified by drawing on scientific developments and technological substitutes to increase outputs of food per unit area of land. The goal is to spare land to support nature conservation – but note that ecomodernists understand “wild nature” to include many landscapes that have long been inhabited and influenced by people. The Manifesto co-authors note that specific approaches to conservation are likely to vary depending on the preferences of local communities, in some cases encompassing a land-sharing model where agriculture and wild nature co-exist on the same land.

The Manifesto mentions few specific agricultural technologies other than (presumably intensive forms of) aquaculture. However, specific recommendations are set out in various publications from The Breakthrough Institute. The report Nature Unbound, written by three Manifesto co-authors, gives examples of both substitution and intensification to help move the food system up a “technology ladder” away from the harvesting of wild biomass, towards controlled production of biomass, and ultimately towards fully synthetic options. Note, however, that ecomodernists do not aim to completely shift to any one mode of production, but rather aim to shift only to the extent required to conserve nature while sustaining societies. Ecomodernists advocate for a food system that:

- Shifts away from unsustainable forms of harvesting of wild fish in favour of sustainable forms of aquaculture – specifically forms that minimise side effects such as eutrophication and the destruction of coastal habitats such as mangroves. Examples include closed indoor tanks that recirculate their water, and fish farms placed in deep offshore waters. Both options rely on low-carbon energy, for pumps, filters, or long boat trips to offshore farms,.

- Favours rearing livestock over unregulated hunting of wild animals for meat (the latter a practice still common in many countries) to reduce harm to biodiversity (particularly because some wildlife can be slow to reproduce, so even low levels of harvesting can be damaging).

- Intensifies meat and dairy production to meet rising demand on existing pasture to spare further land from conversion, and possibly even free up land for nature conservation. Nature Unbound cites a study that finds conventional beef feedlot systems in the United States produce considerably lower environmental impacts across several categories when compared to grass-fed beef systems.

- Replaces draft animals (still used in many countries) with tractors, to reduce the land area used to feed these animals.

- Uses synthetic fertiliser in addition to organic fertilisers. Ecomodernists make the argument that using only organic fertilisers (such as crop residues, manure, compost, human waste, and legumes grown to fix nitrogen) may require twice as much land to produce a given amount of food, compared to using synthetic fertilisers. Ecomodernists seek to reduce nitrogen pollution from all forms of fertiliser, for example by using precision farming equipment to apply only as much fertiliser as is required.

- Reduces harm to non-target species through selective pest control, such as monitoring tools, precise application of pesticides, and genetically modified plants that deter insects.

- Is supported by government investment in innovations such as cell-cultured meat and plant-based alternatives to meat,.

Ecomodernists place relatively little emphasis on reducing impacts through dietary change, although they do note the current disparity in consumption between richer and poorer nations. Instead, the discussion is about how to meet the predicted rise in demand (e.g. for meat) as sustainably as possible. Saying that, The Breakthrough Institute sees the trend of Americans eating pork or chicken in place of beef as environmentally beneficial, although politically difficult to scale up.

|

|

|

| Image: A researcher examines cell culture vessels, Mosa Meat R&D Team, Mosa Meat Press Kit | Image: Drone precision agriculture, Herney, Pixabay, Pixabay Licence |

4. The historical context of ecomodernism

The cluster of ideas associated with ecomodernism can also be found to various degrees in earlier schools of thought that, similarly, tend to view the continued development of technology as essential for protecting nature and for providing sustainable material prosperity.

One example is Ecological Modernisation Theory (EMT), developed in Europe during the 1980s and 1990s within the academic field of environmental social science. EMT calls for the process of modernisation to be “ecologised” using tools such as Life Cycle Assessment, environmental reporting and auditing, eco-labelling, certification schemes and environmental standards to integrate the cost of externalities into the economy,.

Ecomodernism and EMT share several elements, to the extent that American ecomodernism has been described as “reinventing the wheel” of European 1980s EMT thinking. Both schools of thought:

- Do not see “modernity” (which they define broadly, with reference to material wellbeing, public health, and so on) as inherently problematic, and for example do not argue for agrarian societies or for a halt to urbanisation,.

- Allow a central role for technological innovation as a route to addressing environmental and social problems

- Distance themselves from theories such as degrowth that emphasise a reduction in material production and consumption, and

- Support a role for both state and market actors.

Ecomodernism is arguably more normative than EMT: it promotes a specific vision, reflecting its think tank origins. EMT is normative only in the sense that it believes environmental concerns should be integrated into the economy; it does not engage in activism in the same way that think tanks often do.

Ecomodernism also builds on post-environmentalism, outlined by Manifesto co-authors Shellenberger and Nordhaus in their 2004 essay The Death of Environmentalism. Post-environmentalism proposes that, to gain widespread support, environmentalists must anchor their policies to core values held by the public, rather than focus on “narrow” technical issues such as vehicle mileage standards.

Other environmental movements of the 2000s that also view technology favourably include: bright green environmentalism, which distances itself from the perceived misanthropy and frugality of what it calls “dark green environmentalism” and would instead direct innovation towards providing abundant, sustainable goods and service; and technogaianism, which claims that the environment can only be restored using technologies such as geoengineering and biotechnology for treating hazardous waste. Despite some alignment between these schools of thought and ecomodernism, ecomodernists do not appear to directly refer to either frequently.

Critiques of ecomodernism – discussed in more detail below – come from several directions. Many critiques emerge from philosophies focused on scaling down human activity – encompassing population, material affluence, and use of damaging technologies – in a planned and equitable way, to fit within environmental limits. Notably, the degrowth movement argues the need for a planned reduction of material production and consumption in richer countries.

5. Contestations surrounding ecomodernism

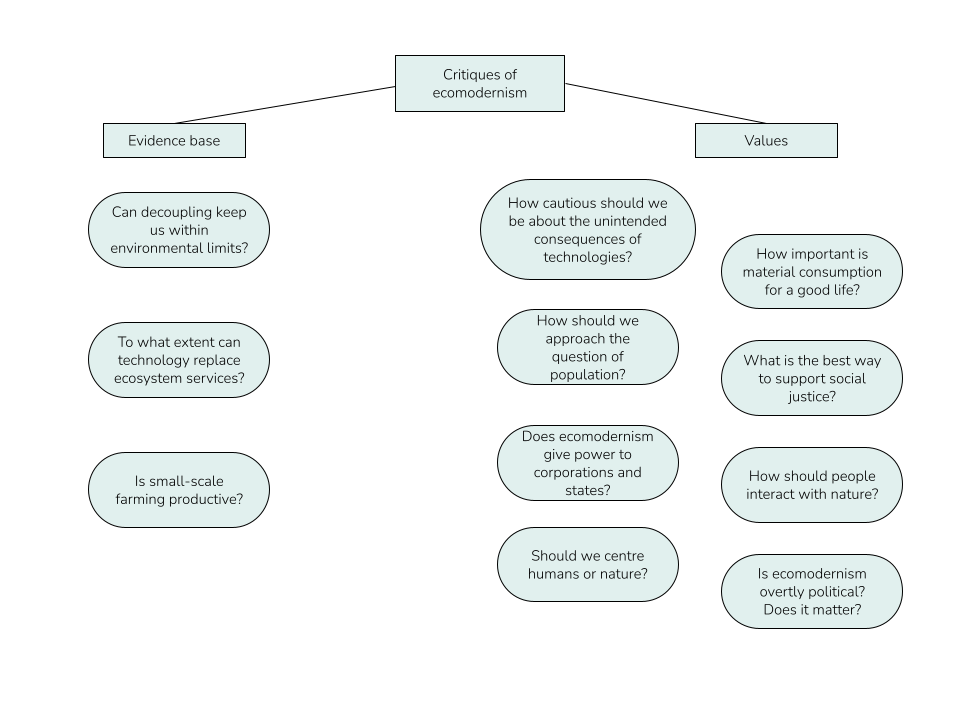

Ecomodernism has provoked significant debate, with critical reactions clustering around both its evidence base and its values (see Figure 2). There is in practice some overlap between the two clusters, since values influence how evidence is selected and used.

With many of the critiques that we describe here, there is a gap between how the critics define ecomodernism, and how ecomodernists themselves define the concept. Ecomodernists may therefore see many of these critiques as “straw man” arguments, while critics may similarly feel that their arguments are misrepresented by ecomodernism’s counterarguments. We have attempted to even-handedly represent the views of both critics and ecomodernists and, where possible, tease out the differences in how each party perceives ecomodernism.

It should also be noted that individual ecomodernists may hold different views on the exact goals and solutions of ecomodernism. We have attempted to reflect some of the diversity within ecomodernism here.

Figure 2: Contestations around ecomodernism, divided very roughly into those linked to evidence and to values. Graphic produced by TABLE.

5.1 Contestations around ecomodernism’s evidence base

Can decoupling keep us within environmental limits?

Is ecomodernism’s intention of providing material prosperity and protecting nature at the same time feasible? Critiques – particularly from the degrowth movement – tend to focus on whether ecomodernism would result in sufficient decoupling of economic activity to stay within environmental limits. We can break this down into several sub-questions.

First, what is meant by environmental limits?

The 2009 planetary boundaries framework quantifies nine environmental limits, including climate change and biodiversity loss, which it argues must not be breached,. Similarly, the 1972 report The Limits to Growth warned that overshooting the planet’s carrying capacity – its ability to provide resources and assimilate wastes – could lead to social and ecological collapse. A connected idea is tipping points: thresholds at which a small “push” (such as additional greenhouse gas emissions) can lead to a runaway feedback loop, resulting in the sudden shift of a local ecosystem or the entire planet to a new state (say, a much hotter climate) that is irreversible on human timescales. Furthermore, one tipping point could trigger others in a cascade.

While ecomodernists acknowledge the grave impacts of environmental damage, some emphasise that some scientists criticise the idea of hard limits in relation to both environmental harm and resource availability.

Regarding resource availability, ecomodernists have suggested there is enough energy available from solar, wind, nuclear and other resources, and technologies to power the production of substitutes for scarce natural resources. As a result, they feel that the theoretical upper limits to resource availability are too high to be a meaningful constraint on material consumption, and that notions of a fixed carrying capacity are faulty because of our capacity to engineer greater yields. The argument that energy availability can circumvent resource availability limits, however, does not explicitly address the materials for which few or no technically adequate substitutes are available, such as some micronutrients in agriculture – the issue being that the factors that limit material productivity might change as output levels grow.

Some ecomodernists argue that planetary boundaries are not a valid concept. What this means in more detail is that – according to Nordhaus, Shellenberger and Blomqvist in a 2012 report – six of the supposed planetary boundaries are not linked to global-level tipping points, and hence any “boundary” set in relation to them is an arbitrary expression of the preferred state of the system. They conclude that environmental impacts in these “non-threshold” categories are better managed at the regional (rather than global) level, and in terms of trade-offs rather than absolute boundaries. The report does, however, say that there are global tipping points in some categories, including climate change, where feedback effects have likely already begun to operate.

Second, is absolute decoupling of economic activity from environmental impacts possible? Note that relative decoupling means total impacts or resource use rise despite increased efficiency, while absolute decoupling means total impacts decrease. Note also that while material consumption and economic growth are not the same thing, ecomodernists tend to speak favourably about economic growth and the Manifesto talks about decoupling in relation to economic growth; meanwhile, studies on decoupling tend to refer to economic growth rather than to material consumption.

Some critics argue, based on historical trends and modelling, that growth will worsen impacts and that ecomodernism is too optimistic – particularly if efficiency encourages rebounds in consumption as described by the Jevons Paradox,,,.

On the other hand, The Breakthrough Institute reports that 32 countries (including the United States and several European countries) have achieved absolute decoupling between their overall economic growth and climate impact (both for territorial and consumption emissions). Absolute decoupling has been reported in a limited number of other cases including global sulphur dioxide pollution, global greenhouse gas emissions from farming, and water extraction in the United States.

There is more evidence to show relative decoupling in some areas: for example, farmland area and wood consumption have declined on a per capita basis over the past few decades (both at the global level), while the totals have increased over the same time period and then appear to be plateauing recently. In other areas, such as water use, total use continues to trend upwards despite plateauing per capita use.

Ecomodernists interpret the trends in relative decoupling hopefully, arguing that they could lead to absolute decoupling this century. Ecomodernists also tend to see economic growth itself as a driver of decoupling: the Manifesto claims that societies can become more resource-efficient as they grow richer and Nordhaus argues that demand for many goods and services saturates as countries grow wealthier,.

Critics dispute some ecomodernist claims about resource efficiency.

For instance, one response to the ecomodernist Manifesto argues that the largest cities use a greater share of the world’s electricity and gasoline and produce a greater share of waste than the share of the world’s population that they are home to. (The data source cited by that response also shows that, compared to their share of population, megacities use the same share of total energy, and a lower share of water.)

While the Manifesto notes that net reforestation is happening in some parts of the world, respondents point out that at the global level, net deforestation continues including in biodiversity hotspot regions.

Several empirical studies question the premise that agricultural intensification leads to a decrease in the area of land used. For example, one finds that simultaneous increases in yield and decreases in the area of land cultivated for ten major crops were unusual, both nationally and globally, between 1970 and 2005, and are more likely to occur in countries that have both rising grain imports and conservation set-aside programmes. Another found that yield increases caused no reduction in per capita cropland use in developed countries, and only weak reductions in per capita cropland use in developing countries. A third distinguishes between different types of intensification: while intensification driven by market demand (say, a shift to crop types with a higher market value) often leads to land expansion and deforestation, intensification driven by technology (i.e. when a technological development permits increased yields for the same level of inputs) tends to lead to land-sparing at the global level. It reports that natural resource governance is needed in addition to technological intensification if deforestation is to be halted – note that, as described above, ecomodernists recommend both governance and technology solutions.

Third, would ecomodernism’s solutions offer sufficiently rapid and large absolute decoupling to avert environmental tipping points? Critics raising this question tend to assume that the planetary boundaries framework is valid. As discussed above there is debate over whether all proposed boundaries actually contain global-level tipping points. Both degrowthers and ecomodernists, however, acknowledge (as noted above) the existence of tipping points in the global climate system.

In The Breakthrough Institute’s decoupling study, the decline in consumption-based emissions over a period of 14 years up to 2019 ranges from 1% (Norway) to 52% (Ireland). Research suggests that no country yet meets all minimum thresholds for the wellbeing of its citizens while staying within its “fair share” of resource use according to the (disputed) planetary boundaries framework and that technological improvement must happen many times faster than is currently the case if we are decarbonise the economy rapidly enough to avoid dangerous climate change. A 2020 review paper concludes that absolute decoupling between economic activity and greenhouse gas emissions is occurring in some countries (driven by environmental policies), but not to the extent required to meet stringent climate targets. Critics including degrowthers fear that ecomodernism is not radical enough to cut impacts quickly, since it abstains from criticising economic growth and argues that people generally seek to follow the consumption patterns of currently richer nations,,,,.

Is small-scale farming productive?

The Manifesto claims that small-scale farming is less productive, but critics say the evidence shows smaller farms, on average, have higher yields per hectare than larger farms, partly because of high levels of manual labour,. Ecomodernists take the view that the relevant comparison is not between different sizes of farms within poorer nations, but between the relatively low yields of any size of farm in poorer countries and the several-fold higher yields of farms in richer countries (where farms tend to be large and intensified). Furthermore, they argue that centring the food system on smallholder labour could trap large rural populations in poverty.

To what extent can technology replace ecosystems services?

As discussed previously, ecomodernists advocate for a general shift away from depending on ecosystems and wild biomass, towards technological substitutes. This should not be interpreted to mean that ecomodernists wish to completely decouple the economy from nature. Indeed, while some critics note that not all ecosystem services can easily be augmented or replaced with technology, ecomodernists also acknowledge this point. For example, while nutrient cycling can be replaced to some extent with synthetic fertilisers, air pollutants can be removed by filters instead of trees, and desalination and water treatment can be used to supplement the natural water cycle, examples of ecosystems services that are harder to replace altogether include photosynthesis and decomposition.

It is worth noting that the term “ecosystems services” is itself contested, for example on the grounds that it may be ineffective in gaining public support for conservation, promotes the commodification or exploitation of nature, and is anthropocentric,. Ecomodernism only aligns to a small extent with market-based views of nature. The report Nature Unbound argues that placing a market value on ecosystems services, as a standalone measure, could help make conservation economically feasible in some limited circumstances and on limited areas of land. It argues that achieving conservation will in most cases require additional measures, such as cooperation of NGOs and policymakers to plan land use, and the active promotion of technologies to achieve higher yields.

5.2 Contestations around ecomodernism’s values

How cautious should we be about the unintended consequences of technologies?

Critics argue that ecomodernism might underestimate the impacts of side effects and unintended consequences of technology, such as nuclear waste, reliance on global supply chains vulnerable to disruption, or the escape of genetically modified organisms or their genes,,. These side effects are often difficult to predict for novel technologies, especially if there are rebound effects on consumption patterns.

The critiques cited above (all published in 2015) appear to have based their assessment primarily on the Manifesto, which does acknowledge some of the impacts of modern technologies, particularly fossil fuels, on ecosystems and the climate. However, the Manifesto gives a very limited treatment of potential hazards arising from monoculture farming, biotechnology, microplastic pollution and overfishing, to give just a few examples. Many later publications from The Breakthrough Institute do address some of these issues in detail. It is therefore not (or no longer) accurate to say that ecomodernists ignore the potential side effects of technologies.

Some environmentalists favour using the precautionary principle regarding novel technologies, which recommends treading carefully when the impacts of a technology are not yet clear. In response, ecomodernists have promoted two other concepts. First, the proactionary principle, which is the idea that failure to use available technologies can be more dangerous than shying away from their possible negative impacts. Second, intended consequences – an idea that emphasises the risks of inaction and favours inclusive decision-making to identify and mitigate the risks of interventions.

How important is material consumption for a good life?

Ecomodernists tend to believe that material prosperity (including access to energy) is a key contributor to quality of life,. In particular, they favour lifting the poorest people out of material poverty even when that increases their environmental impacts,; and some also stress the centrality of social equity in designing conservation programmes. As discussed in the decoupling section above, ecomodernism is uncritical of economic growth, but thinks growth is unlikely to continue at high rates in richer countries. It puts little emphasis on constraining consumption patterns in either richer or poorer countries (in contrast to strands of environmentalism that focus on changing individual consumption patterns, for example by focusing on personal carbon footprints), aiming instead to shift societal systems towards more efficient and less environmentally harmful strategies for meeting societal demands.

Many environmentalists who do not align with ecomodernism also agree with helping people escape material poverty. An early example is the 1987 Brundtland Report, which emphasises that human society risks breaching environmental limits at the same time as stressing the need for “sustainable development” to eliminate material poverty.

Many critics feel ecomodernism simplistically equates modernity and wellbeing with material consumption as well as urbanisation, productivity, and economic growth,. The underlying tension here is about the relative emphasis that people place on the many factors contributing to a “good” life.

Degrowth advocates believes that the current paradigm of economic growth does not satisfy the most important human needs. Instead, they aspire to an alternative vision of progress, which is less founded on material consumption and whose elements include a sharing economy, shorter working hours, meaningful pursuits and community interactions. Elements of degrowth thinking have been drawn from earlier schools of thought including the simple living movement (which has roots in Christianity and certain Eastern religious traditions) and anti-materialist elements of the hippie movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

Some critics feel that ecomodernism pays too little attention to ways of living well that involving consuming less than current patterns in richer countries, once basic material needs such as healthcare have been met. Others feel that ecomodernism is “condescending” towards poorer and less industrialised societies, downplays religion, spirituality, and Indigenous cultures, and sees agricultural labour as a burden from which people need to be liberated.

Furthermore, the Manifesto and ecomodernist writings more broadly say little about the potential downsides of high material consumption (quite apart from environmental impacts), such as the negative effects on mental health of excessive consumerism or ubiquitous advertising. Critics also feel that ecomodernism pays too little attention to the downsides of social inequality within richer countries – for example, to the argument that health and social problems in rich countries are more strongly influenced by income inequality than by average income – and misses the opportunity to alleviate poverty through redistribution of resources.

Part of the difference in perception of ecomodernism here between its critics and proponents is whether ecomodernism is prescriptive or enabling. Critics think ecomodernism pushes one way of life – modern, urban, and based on higher material consumption – as the best and ignores ways of life that do not depend on industrial modernity. Defenders of ecomodernism instead think it merely seeks to give people greater choice in how they live, work, and consume.

How should we approach the question of population?

There are many different interpretations of the significance of human population. Some environmentalists stress the social benefits of slowing or reversing human population growth, such as better access to housing for young people, higher wages, and the empowerment of women,,. Others criticise certain strands of overpopulation discourse (notably 18th and 19th century Malthusianism and the 1968 book The Population Bomb) as racist and misanthropic for giving more importance to managing birth rates in poorer countries than to reducing material consumption in richer countries.

Similarly to many environmentalists, ecomodernists tend to take the view that the process of escaping material poverty is a driver of lower birth rates. Hence, ecomodernism does not perceive a trade-off between poverty reduction and slowing population growth, but rather sees them as synergistic. Ecomodernists predict, based on demographic trends, that our numbers are likely to peak this century, stressing that human reproduction rates are now below replacement level in most of the world.

What is the best way to support social justice?

Part of the reason for ecomodernism’s emphasis on material wellbeing is that ecomodernists believe material prosperity for all is an essential component of social justice. Some ecomodernists also argue that it is more important and effective to provide equitable access to wealth and infrastructure than to focus on the causes of unequal exposure to adversity,. For example, some suggest that environmental policies can provide better health outcomes in marginalised communities when those policies are universal, not specifically aimed at people oppressed by (say) race or class.

However, beyond supporting democracy, pluralism, and the general principle of respecting local preferences, the Manifesto says little about how to resolve long-standing structural power imbalances such as systemic racism and sexism, economic class, or geopolitical relations. Critics say ecomodernism overemphasises the role of modernisation – as opposed to active struggles for social justice – in liberating women from traditional social roles and ethnic minorities from oppression, and argue that social inequality within a country does not fall as wealth grows.

Another critique is that the Manifesto’s conception of “stages of development from underdeveloped subsistence economies to fully developed capitalist service economies” may not be possible, or desirable for all countries to follow, since the wealth of richer countries depends (critics argue) on exploiting poorer countries and people, for example through slavery and colonial violence,,,.

Ecomodernist ideas about social justice appear to be in the process of developing. See for example The Breakthrough Institute’s 2021 special journal issue on Ecomodern Justice. These ideas include: that climate policies in California have placed a disproportionate cost burden on the poorest communities of colour; that the Green Revolution helped India helped to break its dependence on Western grain imports; and that Bangladesh has achieved rapidly improved living standards and self-determination as a country in part through investing in the productivity of its agricultural sector.

Does ecomodernism give power to corporations and states?

Concerns have been voiced in relation to the power dynamics – involving both corporations and states – that may accompany some solutions preferred by ecomodernists,.

Some critics think that the large-scale, intensive technologies favoured by ecomodernism suit powerful, wealthy corporations that have the resources to implement these solutions, and are simply a continuation of existing trends towards intensification, thus favouring the beneficiaries of the status quo. Ecomodernism has therefore been critiqued as entrenching unjust or exploitative power structures, for example by protecting the existing economic interests of private industry, deepening wealth inequalities, undermining or doing nothing to enhance land rights for indigenous peoples, small scale farmers or the general population (on account of its association with land-sparing), or doing too little to rebalance the influence that profit-driven corporations and lobbyists have over environmental policies and consumption patterns.

The Manifesto argues that modernisation is not synonymous with capitalism and corporate power, on the basis that modernisation is a broader process including social, cultural, economic, political, and technological development. Furthermore, some ecomodernists argue that the most effective way to conserve biodiversity is to empower Indigenous and local communities.

From another perspective, free market thinkers might be equally concerned about the power dynamics or market distortions caused by the top-down government interventions that are also favoured by ecomodernism, for example subsidies and environmental regulations. It is not surprising that ecomodernism might attract criticism from both left- and right-wing thinkers, since it does not fall neatly at either end of the traditional political spectrum and instead contains elements of both camps. Given ecomodernism’s stated preference for locally and nationally determined technological solutions, as opposed to top-down choices, criticisms tied to specific policies or technologies may not reflect the full diversity of views held by ecomodernists.

How should people interact with nature?

Ecomodernism’s proposed relationship between people and nature has been critiqued in several ways.

One critic says that ecomodernism relies on “outdated notions of nature as passive, pristine and only able to prosper apart from us”. If true, this could be problematic because the trope of “pristine nature” has historically been used by state and colonial powers to justify violence, such as the ejection of Indigenous people from what was incorrectly seen as wild, unused land by settlers in the United States.

However, many ecomodernists would strongly reject the accusation that they rely on the notion of pristine nature, and indeed some stress that conservation can succeed in the context of many different human cultures. The Manifesto and some separate publications by its authors note that most landscapes have been influenced by humans for millennia, and that there is no clear “pre-human” baseline to which landscapes can be returned,. Ecomodernists assert that using some land intensively to spare other large swathes of land for conservation or restoration of nature does not require a belief in pristine landscapes.

Another critique is that ecomodernism presents a “polarised” vision of clearly separated areas of “nature versus non-nature” – a perception that seems to be based on ecomodernism’s aim of making more room for nature conservation.

The Manifesto does praise the potential of urbanisation and intensification for making more room for non-human species. However, it recognises that not all communities will choose a land-sparing model, and ecomodernists favour varying degrees of human interaction with areas of “nature”. For example, Emma Marris favours the “interwoven decoupling” model, in which there are extensive conservation areas, but in which all people also have access to a variety of green spaces for purposes ranging from urban vegetable gardening to traditional food gathering to rock climbing. Erle Ellis argues that the traditional uses of lands and waters by local and indigenous communities are generally crucial to the success of wildlife conservation measures.

There is some debate as to whether and why people in industrial societies might value nature. Ecomodernists argue that people tend to care more about conserving wild nature when they no longer depend directly on it for their physical wellbeing. Other thinkers, including some ecomodernists, argue that in fact it is poorer communities who are dependent on nature who are at the forefront of defending ecosystems against actions by corporations or states.

In a contrasting ecomodernist view, Ruth DeFries says “there’s no intrinsic value to nature for most people and that’s okay”. Indeed, ecomodernists depart from environmental movements that assign intrinsic value to rural living or nature itself, and would prefer to move away from some traditional, Indigenous, or subsistence practices in the cases they are carried out at unsustainable levels, such as environmentally harmful levels of firewood or bush meat harvesting.

Should we centre humans or nature?

Ecomodernism primarily takes an anthropocentric approach – that is, it centres human wellbeing, while seeing human thriving as connected with conserving ecosystems and species (as do some other strands of environmentalism). Some critics think ecomodernism sees humans as the ones who should decide what happens to nature.

Schools of thought that differ from ecomodernism’s human-centric framing include deep ecology, which believes that all living beings have inherent value regardless of their utility to us, and sentientism, which assigns moral worth to beings (including humans, animals and artificial intelligence) depending on their capacity to experience “suffering and flourishing”. These movements may see ecomodernism as lacking through not giving non-human individuals, species, or ecosystems moral status. Deep ecology critiques technofixes as too narrow in scope and condemns “industrial culture” for treating nature only as a convenient, profitable resource.

Arguably, ecomodernism and non-anthropocentric movements such as deep ecology place similar levels of importance on making space for non-human life to flourish, but they do so for different reasons.

Is ecomodernism overtly political? Does it matter?

Finally, there is a cluster of concerns around the political motivation of ecomodernism. Nordhaus and Shellenberger have experience in communications, opinion research, and politics (Shellenberger ran as a Democratic candidate for governor of California in 2018). Critics suggest they may have used this expertise to carefully construct an environmental narrative with values that appeal across political divides, for example to gain the support of people concerned with jobs, security, and economic growth. The concern is that such a narrative may avoid less politically acceptable – but, in the eyes of critics, necessary – environmental measures, such as lifestyle change.

Some critics say that ecomodernism is covered widely and positively by the media, which they attribute to its partial alignment with the media’s preferred political and economic narratives (such as progressivist thought and capitalist market systems),,. Indeed, if ecomodernism was indeed conceived with political popularity in mind, it would make sense that it is well-received by some media outlets. However, some ecomodernists feel that the media instead prefers environmental crisis narratives instead of those that align with ecomodernism’s preferred solutions. Our reviewers were divided on the point of whether ecomodernist narratives receive favourable media coverage.

The counterargument to concerns about political motivation is that framing messages to align with the target audience’s pre-existing beliefs or values is a pragmatic and widely researched approach for increasing the effectiveness of environmental interventions, as opposed to a harmful approach. Emphasising alignment with widely held values may be necessary if environmental conservation is to become politically successful in democratic countries. Indeed, one co-author states that the Manifesto was aimed at people who are dissatisfied with both the perceived negativity of traditional left-wing green politics and the lack of serious attention given to environmental issues by some right-wing free-market thinkers.

6. Conclusion

Ecomodernism aims to provide material prosperity for everyone while minimising harm to the biosphere. It sees technological progress as an important method of partially decoupling humanity’s material requirements from nature by intensifying production of goods such as food.

In seeking solutions that serve both people and the planet, ecomodernism has drawn criticism from those who: think technology does not offer sufficiently rapid decoupling between economic growth and environmental impacts; argue we should be cautious about the unintended side effects of novel technologies; feel it does not fully acknowledge the significant tensions that can exist between material consumption, social justice, and ecology; fear that it does not sufficiently address questions of power and therefore underestimate the extent to which corporate and state power dynamics can hinder environmental action; question its ideas about what makes for a good life; or are wary of its preference for urbanisation and land-sparing.

Environmentalists and social justice advocates may find themselves torn between ecomodernism’s advocacy of economic development to reduce poverty and the idea of seeking ways of living well that shrink human activities and our material consumption to minimise harm to the biosphere . Where can a pragmatic balance be found, particularly as we approach potential tipping points in the climate system? Will policies to support transitions to new technologies and further development of those technologies be quick enough, or do we need – additionally or instead – policies that incentivise drastic short-term changes to lifestyles in richer countries? Is thinking in terms of trade-offs between prosperity and environmental impacts the best approach, or are prosperity and sustainability synergistic?

Technologies such as meat substitutes and solar panels are advancing rapidly, and even some critics of ecomodernism have embraced the game-changing potential of new technologies. For example, environmental writer George Monbiot, who has spoken out against ecomodernism’s understanding of modernity, believes “farmfree” fermentation of protein using microbes could free up vast swathes of land for rewilding and carbon sequestration – an approach in line with ecomodernism’s tendency to prefer land-sparing, although at least one ecomodernist thinks that energy requirements make this scenario impractical in the short term,.

Significant questions remain as to how ecomodernist approaches would play out in practice over the long-term. For example, what happens when ecomodernism encounters local preferences that go against its default assumption of land-sparing, for example in areas where extensive farming has significant social, economic, cultural, spiritual, or emotional benefits for people? And what role would belief systems other than “Western” science, for example Indigenous frameworks for ecological management, play in shaping an ecomodernist food system?

As discussed in the box at the start of this piece, we asked reviewers from both ecomodernist and critical perspectives to comment on this piece. We found several issues where the opinions of some reviewers were in opposition to each other, to the extent that it was difficult even to describe the disagreements in a manner acceptable to all parties. Some of the key areas of tension were:

- Whether the planetary boundaries concept is scientifically valid. One reviewer was of the opinion that it is problematic even to mention the idea of environmental limits or planetary boundaries as a critique of ecomodernism, for fear of giving those critiques more credibility; another assumed that most people agree on the idea that we should avoid critical thresholds of environmental damage.

- The relationship between ecomodernist narratives and the media. One reviewer viewed ecomodernism as essentially a form of “business as usual” and therefore in line with mainstream media narratives and framings, while another felt very strongly that ecomodernism is unpopular with the media.

- Whether the ecomodernist movement acts in good faith. One reviewer felt that ecomodernism is a tactic to protect the beneficiaries of the economic status quo, while another felt that this perception is a slur (to ecomodernism) so unjust that it is better not to mention it.

- Whether agricultural labour is a burden from which people should be liberated. Some reviewers agreed with this criticism of ecomodernism, on the grounds that ecomodernists promote an urbanised lifestyle as the best or most desirable way of living. Others took it for granted that agricultural labour is burdensome, and were surprised that “liberation” from agricultural labour could be seen as a negative or inaccurate framing by critics of ecomodernism.

It is outside the scope of this piece to settle the science on whether there are indeed planetary boundaries or to assess media bias towards or against ecomodernism. What instead we have tried to do is identify some key underlying tensions that fuel the divide between ecomodernism and strongly differing movements such as degrowth. The review process has, however, also shown some points of consensus:

- Despite disagreement about planetary boundaries, reviewers from both ecomodernist and critical perspectives agree that tipping points exist in the climate system.

- One “degrowth” reviewer agreed with the ecomodernist point that non-threshold boundaries should be managed locally, not globally, and wished that the degrowth movement would acknowledge this point more strongly.

- Multiple reviewers agreed with the importance of drawing a distinction between the ecomodernist perception of itself as enabling greater freedom in lifestyle choices, versus the degrowth perception that ecomodernism prescribes certain lifestyles.

- Multiple reviewers also stressed that ecomodernism is an overarching term that encompasses a diversity of viewpoints; and that the same is also true of critical movements, such as degrowth.

This piece has been far from comprehensive. To summarise the key features of ecomodernism and the contestations that surround it, we have inevitably simplified both the range of views that exist under the umbrella of ecomodernism and the views of critics. The concept of ecomodernism is linked to many highly polarised debates about how we should live well and respond to sustainability challenges, with disagreements reflecting contradictory worldviews as well as differing interpretations of what the very word “ecomodernism” means. Our aspiration is that the piece has offered some insight into why the idea of ecomodernism is so contentious. We hope it will serve to feed further dialogue on ecomodernism and the overarching principles linked to it.

Comments (0)