This piece is written by Tamsin Blaxter, researcher and writer at TABLE, as part of TABLE's work theme Power in the food system: what’s powering the future of protein?

At TABLE, we have been busy planning our work for the next few months, all of which is to be linked by the theme of power. We are treating power in food systems both as a topic and as the lens through which we view other topics. It guides the questions we can ask—where is the power located in this system? Who is prompting change or stability, and what values and what visions for the future motivate them? What are the tools (narratives, systems, relationships) by which power is exercised?

This lens can also be turned on TABLE in (at least) two ways. We can think about how power operates in our organisation. In doing so, we might consider our internal group dynamics and our relationships with other organisations who influence us or whom we might hope to influence. But we can also think about what power we have in the context of the wider food system and what we choose to do with it. We are neither policy makers nor food producers or distributers; operating as we do in a liminal space between academia and civil society, such power as we have lies largely in influencing the direction and content of stakeholder dialogue, and so is most clearly exercised in our decision-making process—the choices we make about what to write, who to speak to, whose voices to platform. In the spirit of the theme of power and the questions it raises, this piece is an exercise in opening, querying, agitating that process.

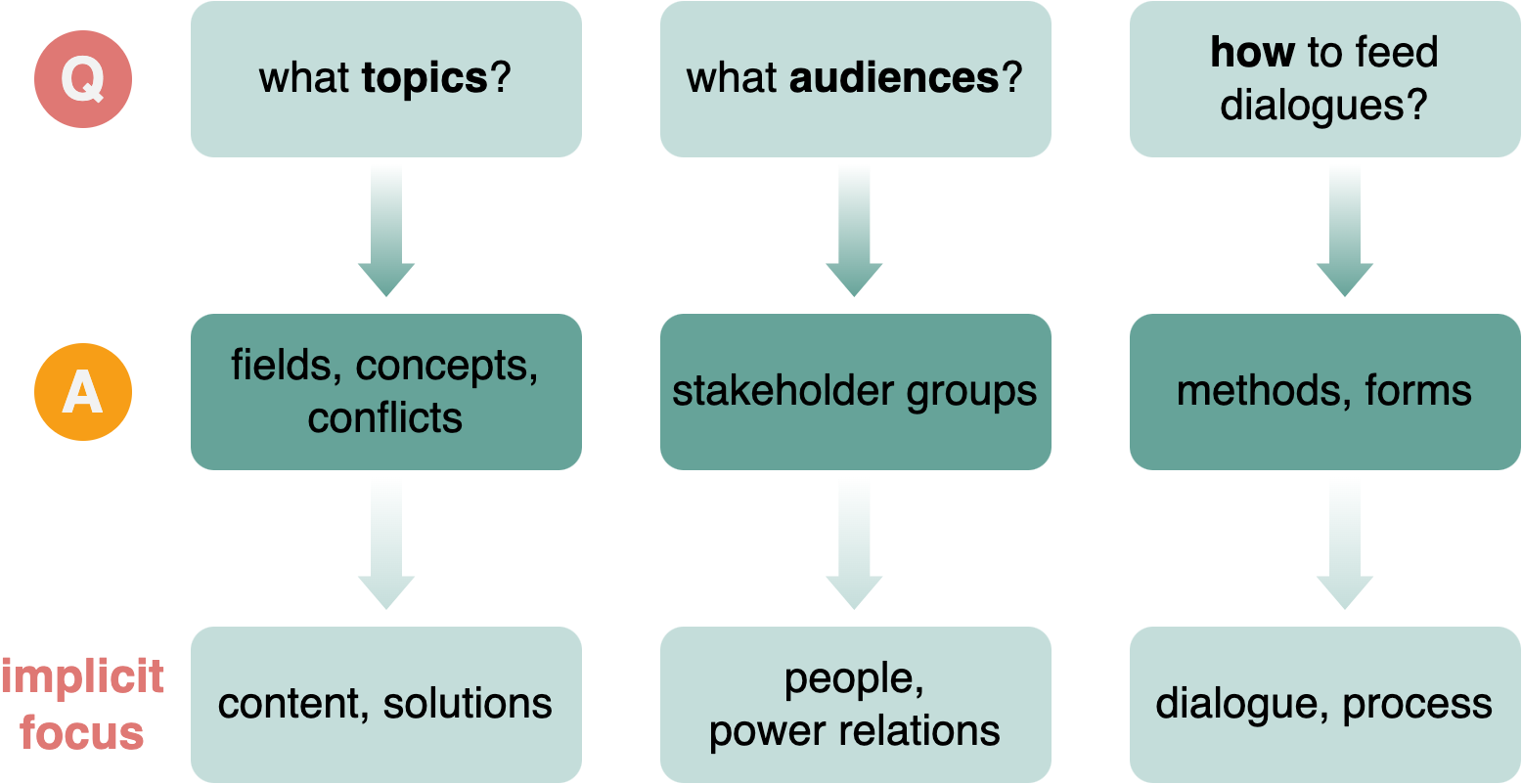

The discussion reported here builds on a conversation we had at an internal meeting to review the latest draft of the workplan for our what’s powering protein theme. The workplan set out and described the outputs we wanted to produce: blurbs for explainers we wanted to write, a list of guests to interview for podcast episodes we envisaged recording, events we hoped to organise on different subjects along with ideas for speakers. The structuring principle of the draft was content—what topics the outputs would cover—but we soon realised that this was not the only way we could have organised our thinking. If we structure our plans by content then content will be foregrounded in our discussion, framing our decisions with the question what topics is it most important to cover when thinking about power in food systems? If instead we were to structure our plans by audience, by different stakeholders in the food system, would that help us to focus on the question are we speaking to all the audiences we would like to reach? Were we losing sight of some stakeholders (and perhaps specifically over-serving academic audiences) with our content-driven approach? Were we taking a techno-fix approach to our work, falling into the trap of focusing on whats rather than hows? If alternatively we were to couch our planning process more explicitly within our mission to facilitate better dialogue, would that help to keep us focused—keep us ‘on mission’? The framing question might then be how will these outputs facilitate dialogue about power in the food system? And of course, how, within our organisation, will we answer these questions and who will decide?

Figure 1: Devising a programme of outputs

Dialogue and power

Our internal processes, like those of any organisation, are reflective of multiple power dynamics. We must be responsive to the goals and expectations of our funders. These funders include the universities in which we are embedded, as well as the Quadrature Climate Foundation, a major supporter of our work. We need also to consider advisory board members, who agreed to give their time on the basis of a certain understanding of who we are and what we do. We are constrained by the online platforms through which we reach audiences, by the approach and interests of traditional media who might or might not choose to amplify our work, and by our own skills, experiences, interests, backgrounds and personalities. Which master(s) are we serving when we choose what topics to work on and how to go about exploring them? Hopefully one answer will always be our mission and the vision of a better-informed, more open and less polarised network of actors in the food system, and to protect this goal we deliberately choose not to accept funding from certain sources. For example, we would not accept food industry funding out of a concern that this would influence the work we could do—even unrestricted funding could lead us to self-edit, consciously or unconsciously. Nevertheless, with so many forces pulling in different directions, it is important to be clear-eyed when asking ourselves this question, and to document our process and the reasoning behind it.

The stakeholders most central to our goals fall into three groups: civil society (NGOs, community groups, non-profits, charities); policymakers; and the business sector, both corporate actors in food systems and smaller farmers and food producers, each group with different kinds of power and different constraints on that power. We see our role as helping these groups to reflect on their assumptions and ask themselves questions of what they are doing, giving them platforms to speak openly to one another and, in doing so, facilitate clearer dialogue and decision-making. Our other audiences include food systems academics and students, and the general public, but these are not our primary focus. Given this, we should ask whether we are always clear who particular outputs are intended for. Perhaps we are best at speaking to academics and so could always easily drift into this mode, but this is not our most important stakeholder group because they are typically already well served, both in terms of information resources and platforms to speak.

It is also important to us to consider the relative degrees of power held by these different stakeholders. Should we focus our engagement on those with the power to enact material or cultural change—thereby maximising the direct impact of whatever positive influence we can exert—or on those without power—who stand to benefit most from the platform we offer? With the former strategy we risk being subsumed into existing groupthink; with the latter, making only symbolic achievements. Our ideal strategy might be to bring the two groups together, so that the interests of the powerless can figure more in the decisions of the powerful, but this is a narrow path to walk.

Agenda setting and power

The main lever of power we have is that of agenda setting: by choosing what to write and speak about and who to platform, we help to direct conversations and inform their content. We should be open about how we use this lever in trying to achieve positive change. For example, our workplan for the power theme includes a thread focusing on Sub-Saharan Africa, which relates to a general aim that our audience must include those in the Global South. The Global South comprises a large majority of the world population—on this basis alone, we reject the possibility of meaningful conversations about the future of food without the full involvement of actors in the Global South. This is a normative position—a statement of value—and just as we try to throw a light on the value systems that motivate others, we aim to be open about our own. But this has to be set in the context of empirical observations: a great majority of well-resourced platforms for dialogue and sources of information are based in the Global North, often behind paywalls, and policy discourse in the Global North often ignores the concerns of the Global South. We and our funders are based in the Global North, and it would be naïve to expect inclusivity to be an automatic consequence of good intentions. Rather, we must be conscious and active in following this aim.

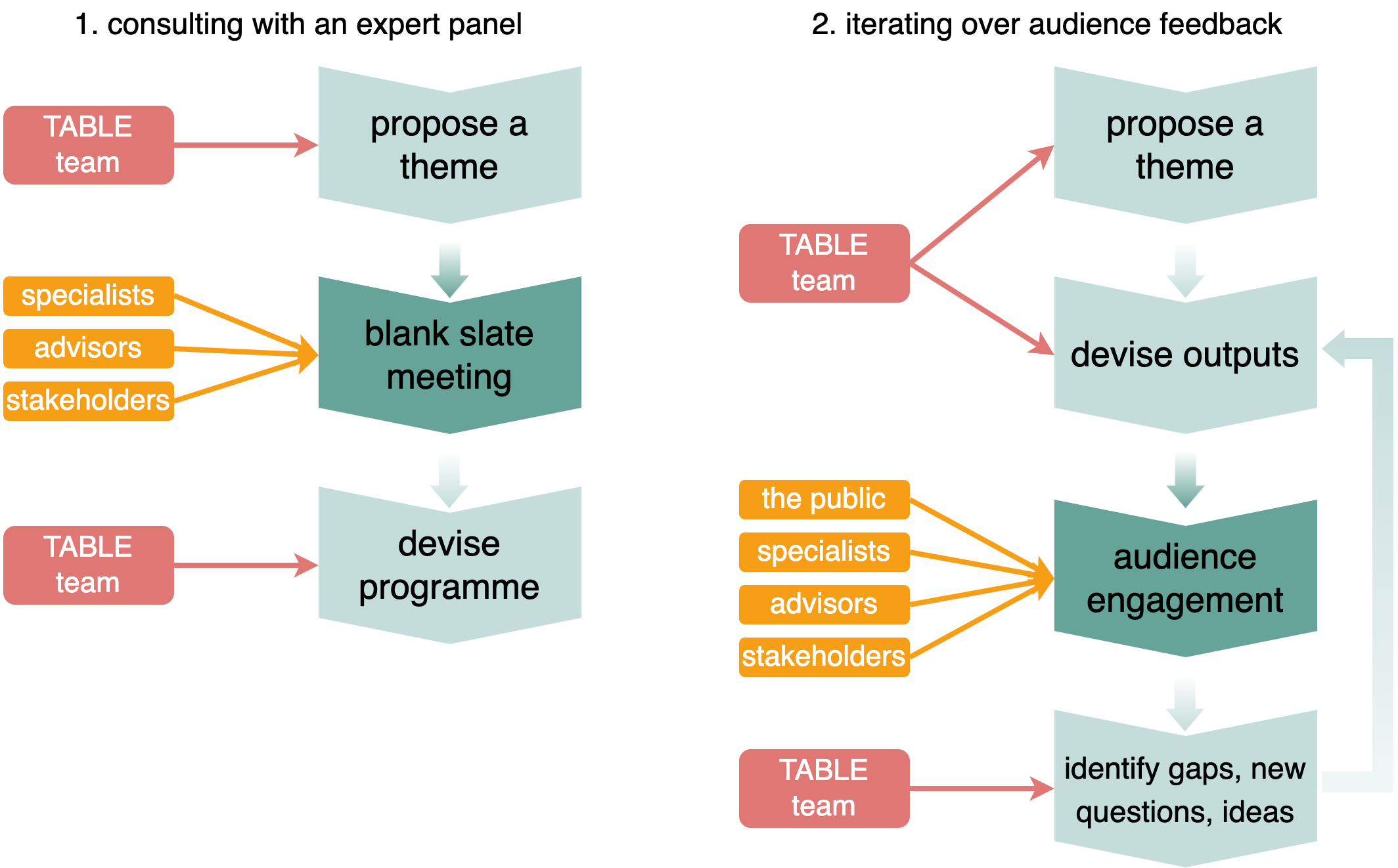

Another of our process goals is to democratise our agenda-setting by involving parties external to TABLE more actively. This would be in line with our values, but also has practical benefits. Our perspectives are limited by our personal identities, histories and the contexts in which we work; by involving others in scoping what we should write and speak about, we can better identify the emerging topics that matter to people. How, then, can this be done? One option is to convene a group of specialists and stakeholders whose expertise we can draw on when devising a programme of outputs. We could hold ‘blank slate’ meetings with such a group early in the planning process where we ask for ideas about how we might approach a theme with minimal constraints or preconceptions.

Another option would be to incorporate engagement with stakeholders and researchers into our planning processes fluidly. To take the example of the power theme, our recent opening event (Power in the food system – an open-ended discussion) was intended as an exploratory and open discussion. By avoiding setting our future plans in stone beforehand, we get the opportunity to use the interests that the panellists and audience express at events like these to prioritise among the possibilities—and use reflections at these events to spark new ideas. With this approach, the conversation we are having now can serve as a reminder to us to remain open to listening to those we want to serve, rather than a prompt to create an entirely new structure.

A variation on this would be to follow an iterative process. We create a set of outputs and engage with the audiences they attract. We aim to identify what questions our work raised for these audiences and what gaps were present, what we missed—and then interrogate these through the next set of outputs. This spiralling structure would hopefully allow us to touch on matters within our theme important to many different audiences, and could itself be seen as a performance of dialogue (between stakeholders and ourselves, between different stakeholder groups). However, it would carry the risk of becoming a positive feedback loop magnifying the perspectives of the stakeholders we find easiest to engage.

Figure 2: TABLE decision-making processes

Openness and power

For us to achieve our goals, we need stakeholders in the food system to view us as trustworthy and fair interlocutors. Our instincts—coming from academia—are that trust is gained through scrupulous attention to detail, creating outputs so thorough that ‘no-one can disagree with them’. Yet in messy reality, where (choices of) facts shade into ideology and values, this is often impossible. So what should we do? If we look at news media organisations like newspapers, there is no expectation that the reader will agree with every single opinion piece published in any particular given newspaper that one chooses to read. Nevertheless, ideally the reader’s trust can be gained because the journalistic process, the principles behind it and the organisation’s goals are constantly made visible (through linguistic signalling in core reporting, through explicit discussion in editorials, op-eds, and in monologues by podcast hosts and news anchors). If we do something similar and aim to make our process and our thinking visible, it might lessen the pressure on individual outputs to be perfectly complete and unchallengeable on every front, since this will no longer be the (sole) plank on which the weight of trust is placed.

This approach of ‘showing our working’ is also in line with our values and consonant with the theme of power. Simply by having a platform, we have power, and we inevitably use that power in unconscious and automatic ways—many of which we may not recognise ourselves. We can improve this situation—be more responsible, responsive holders of power—by exposing the processes by which we work, showing how we get to decisions.

All this said, there is a tension between the desire to be a reflective and careful actor in the information ecosystem and the need to act quickly: this is a climate crisis! There is a risk that all of this will be merely navel gazing (or be perceived as such). One could call this the hurry-hurry / think dilemma, and there are no easy answers here. We hope that a balance can be struck between accessible openness and self-absorption.

Conclusions

It is often remarked that power is everywhere but nobody has it. No-one thinks that power resides with them—we have observed this ourselves when speaking to stakeholders. Smallholders, CEOs and heads of state: everyone is part of a larger web and much more acutely aware of the constraints under which they operate, the other people or institutions who would also have to act for transformative change to be achieved, than they are of their own capacities. This is a trick of salience, a cognitive illusion by which power seems to disappear altogether, to sit disembodied and ghostly in an abstract system, accessible to no-one. Under such an analysis, no actor would ever have the power to enact change.

Thankfully, such an analysis would be wrong. History is not the story of a single, unshifting status quo since time immemorial: dialogue takes place, people’s minds change, and with them their actions, and with those the world. One necessary step among many, then, if we are to create a more sustainable and equitable food system, is for stakeholders to make realistic assessments of their power—how it is constrained, yes, but also where it is located, how they are using it now, how they might use it in future. We hope that we have shown in this piece that we are trying to do that ourselves at TABLE.

Another necessary step is that actors in the food system gain confidence in each other enough to move from debate to dialogue, from talking at to engaging with. This doesn’t mean assuming that everyone shares the same goals and interests or that anyone can be an unbiased interlocutor. But it does mean building mutual understanding of how different stakeholders’ positions and goals do and don’t overlap, and developing trust that mediating voices are operating in good faith.

Much of this discussion could be summed up very simply by asking ‘Are we asking the right questions?’ This formulation encompasses all the nitty-gritty of planning out what should be included and what is deemed irrelevant when writing an explainer, which guests should be invited and what topics they should be asked to speak on at an event, whether the topics we’ve chosen resonate with our readers and listeners. But it also implicates questions of process and power. How do we resolve internal conflicts? Are we using our own power conscientiously, reflecting the world we want to see in how we operate internally as well as in the work we put out into the world? Which stakeholders really do hold the power to transform the food system? Is our goal to speak truth to power or amplify the speech of the powerless? Are we spending too much time on reflexive thinking instead of hurrying to act? How, in short, do we hope to promote dialogue and achieve positive change in the food system?

None of these questions—neither the more prosaic nor those addressing the big picture—have simple or set answers, and there was no chance that one conversation would clarify them for good. Instead, we are operating in the mode of consideration, experimentation, refinement. We aim to keep the big questions in view alongside more day-to-day matters, assess how and whether we are achieving our goals, and change our processes whenever necessary—and do all of this openly. We do not expect to find perfect answers, but to move towards being as responsible and effective an organisation as we can be. This piece reflects one step in our thinking towards that goal.

We welcome your thoughts! Leave a comment below or post on the TABLE community platform.

Comments (0)