Ellen Fletcher holds a BSc and MSc from Imperial College London, Centre for Environmental Policy. Her research has previously focused on urban agriculture (UA) where she has provided evidence on the importance of allotments as a form of UA in sustainable cities. Ellen is currently a research assistant at Rothamsted Research, where she is part of an EU Horizon 2020 project working with farmers in the South West. Ellen would like to pay particular thanks to Catherine Broomfield for initially introducing her to the topic of global and local food systems in her seminar “Livestock farmers: prophets or pariahs?”. Catherine’s extensive body of work on UK livestock systems can be found here.

Food consumption is a topic under increasing scrutiny with almost all emerging publications on the climate crisis giving the topic time in the spotlight. The overarching consensus is that reducing individual consumption of animal products can pay dividends in fighting the global climate emergency. I want to be clear: I’m not here to dispute this. Are, however, the problems and solutions as simple as we are currently being told by environmental literature, the popular media and, increasingly, the public narrative?

The Oxford University collaborative project Our World in Data (OWID) has published the striking article: You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local (Ritchie, 2020). The message behind the publication is seemingly simple: eating locally produced food makes very little difference to your carbon footprint as the relative contribution of transport in livestock’s total carbon footprint is very small. A worked example (accessible via the drop-down box in the article) shows the steps taken to reach this conclusion. In brief, the method is as follows:

- The average carbon footprint for a range of food types were taken from Poore & Nemecek, 2018. For beef, this is 60 kg of CO2 eq./ kg, on average across a range of production types and locations. This figure is considerably larger than the average figures for other food types – for example, peas average at 1 kg CO2 eq./ kg.

- The emissions from transport (national versus international) are calculated as a proportion of these global average footprints. Imported beef is assumed to travel 9000 km by boat.

- For beef, where the global average footprint is so large, the contribution of long-haul transport is equivalent to just 0.35% of the total footprint and is essentially negligible. Eating locally therefore makes little difference for total emissions, according to the article.

The article was rapidly shared online via various social media platforms. On Facebook, the webpage URL racked up nearly 280k engagements (shares, comments and reactions) in the first month of publication with 36.3k of these being shares of the article. (These figures are from SharedCount, a tool that tracks engagement with URLs. The site used the Our World in Data article URL and engagements were counted from publication (24/01/20) to 25/02/20.)

So, why should you think twice about their recommendations? It all comes down to the need to distinguish between local and global food systems and I argue that statistics from one cannot be sweepingly applied to the other. In using global average emissions to study local systems, the article assumes that the environmental benefits of eating locally are determined solely by transport emissions savings – an assumption that does not hold up.

Local versus global scales

Not all food systems are the same and how food is produced varies globally. Organic, pasture-fed, local UK beef is evidently very different from grain-fed cattle or beef ranched on former rainforest land in South America. For clarity: these systems are not necessarily better or worse than each other, but different (a topic already discussed at length by the FCRN in the report Grazed and Confused? (Garnett et al., 2017)). It seems obvious when extremes such as this are cited, but the failure of scientific publications and media alike to recognise these differences is driving the misrepresentation of agriculture and fuelling increasingly vocal, siloed views.

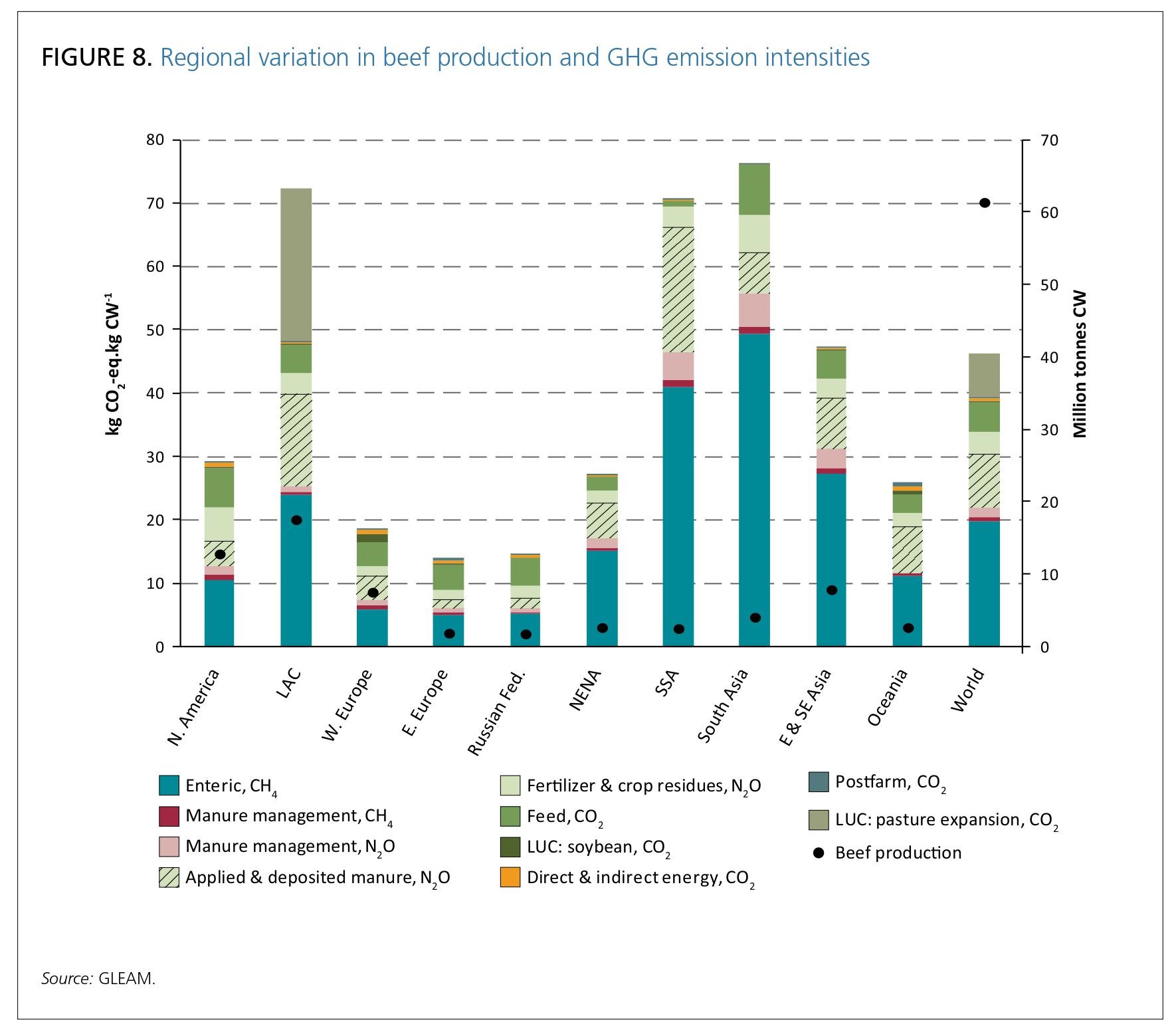

The environmental impact of livestock is considerably influenced by its production processes and varies globally. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has modelled these regional differences using its Global Livestock Environmental Assessment Model (GLEAM). The findings are shown in Figure 1 which has been reproduced from their ‘Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock’ report (Gerber et al., 2013).

Figure 1: Regional variation in beef production and GHG emission intensities. Data source: GLEAM. Figure taken from the Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock report (Gerber et al., 2013).

Figure 1: Regional variation in beef production and GHG emission intensities. Data source: GLEAM. Figure taken from the Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock report (Gerber et al., 2013).

Figure 1 reiterates that simple global averages do not convey the huge variation in emissions from livestock globally. In fact, the study from which Ritchie (2020) took the global average figures also makes this point. The authors argue that the environmental impacts of products are highly variable and skewed by producers with particularly high impacts – for beef originating from beef herds, the 25% of producers that have the highest impacts produce 56% of beef’s GHG emissions (Poore & Nemecek, 2018).

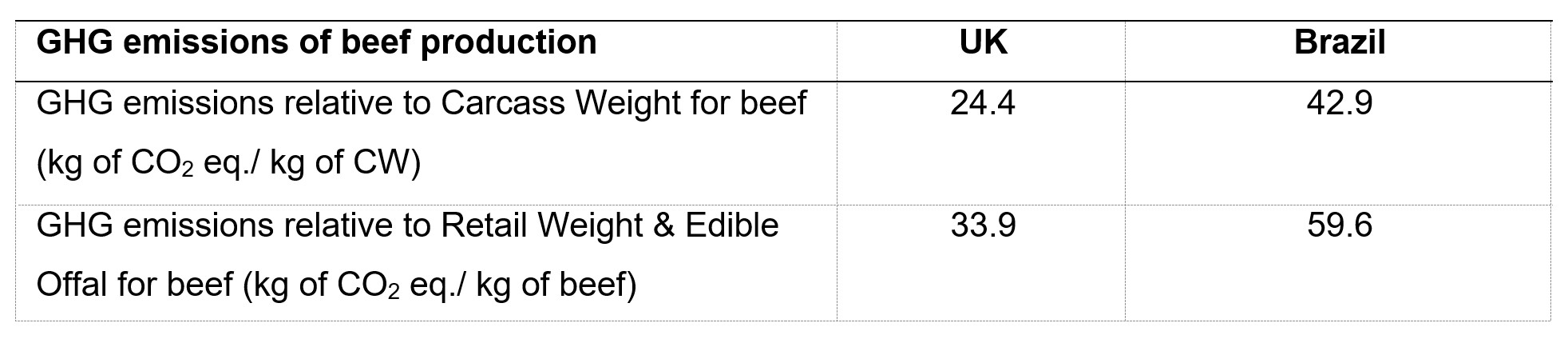

GLEAM-interactive can be used to show the regional differences between UK-reared and South American-reared imported beef cattle. In the example below, eating local UK produce reduces the environmental impact of beef consumption by 43% relative to eating beef imported from Brazil. This saving does not come from reduced transport emissions, but from differences in production before the farm gate. Brazilian beef was chosen to represent an import with similar transportation distances to those cited in the OWID example. While only 1.2% of the UK’s beef imports come from Brazil, Brazil is the UK’s largest non-EU supplier of beef and the UK’s beef imports from Brazil increased by 45% in the last financial year (AHDB, 2019). While this one example may demonstrate the environmental benefits of local produce, it is extremely production-specific and this must be recognised.

Table 1: Values taken from the FAO GLEAMi calculator. Emissions were calculated using relative contributions of beef from specialised beef herds and dairy herds (compared to the OWID article that only considered specialised beef herds). As the environmental burden of dairy herds are split between milk and beef production their GHG emissions are comparatively lower (globally: 18.2 kg of CO2 eq./ kg of CW compared to 67.6 for specialised beef herds) (Gerber et al., 2013). The bone-free-meat to carcass weight ratio (0.72) was used from Poore & Nemecek, 2018.

Applying global averages to local scales fails to recognise these differences in production and, therefore, footprints. By solely considering the transport emissions for local and international produce and ignoring the differences in the impacts of production we are doing local food a huge injustice in the cases that local food has lower environmental impacts than imported food. This is not to say we shouldn’t study food problems from a global perspective; rather, local recommendations should not be extrapolated from these global scale studies and, importantly, clear signposting should be used to indicate if a statistic applies to the global or local perspective.

It is also worth mentioning that the focus itself on Global Warming Potential (GWP) and CO2 eq. is, by nature, too narrow to truly assess the costs and benefits of eating local produce. Environmentally, CO2 eq. fails to capture wider externalities associated with food production (such as the interplay between farming and biodiversity or water quality). The costs and benefits of eating locally are also not restricted to the environment. Focusing only on the metric of CO2 eq. fails to consider societal and economic consequences of local versus global food systems.

Potayto-potahto: why does it really matter?

We are at a crucial time in discussions on sustainable food and the debate is becoming increasingly polarised. This is understandable, with so many vested interests – whether they be social, ethical, economic or environmental – the future of food is an emotive topic. Sustainable food production, however, requires that farmers and consumers work collaboratively towards a better future and so we must find some middle ground if we are to move forward. This is perhaps where science can play a part. Research should be used as a tool to provide clarity on sustainable food systems and to inform decision-making for both producers and consumers. However, it must be robust and thorough so as to inform the debate without introducing bias. Interchanging between global and local statistics, if not done carefully, confuses the already messy narrative of sustainable food production.

When assessing local systems, instead of simplifying the debate we need to be asking more questions. What is the agro-ecological context – how was this food produced and where? This part of the debate is often brushed under the carpet perhaps because the narrative is not as simple as “good food versus bad food”. Looking forward, the focus of the food debate must shift to look at the quality of food (and all food, not just animal-based products) in addition to the quantity consumed. Of course, this is difficult and complex, but it is necessary if the UK food system is to play its part in mitigating climate change, improving our local environments, reducing pollution and improving biodiversity and soil health.

References:

Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB)., (2019) The UK cattle yearbook 2019. AHDB. Available from: https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/the-uk-cattle-yearbook-2019 [Accessed 3 April 2020]

Garnett, T., Godde, C., Muller, A., Röös, E., Smith, P., de Boer, I., zu Ermgassen, E., Herrero, M., van Middelaar, C., Schader, C. and van Zanten, H., (2017). Grazed and confused. Food climate research network, 708.

Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A. and Tempio, G., (2013). Tackling climate change through livestock: a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Poore, J. and Nemecek, T., (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), pp.987-992.

Ritchie, H., (2020). You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local. Our World In Data. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/food-choice-vs-eating-local [Accessed 27 February 2020]

Post a new comment »